Revisiting the social and political theory of social classes

Spyros Sakellaropoulos

Revisiting the social and political theory of social classes

1. Introduction

The question of the theory and characteristics of the contemporary working class acquires great importance in the light of the new theories of ‘globalization’, the ‘end of labour’, ‘monadic thinking’ (pensée unique), etc. This essay aims to show, on the one hand, how the Marxist approach to the social classes is an efficient methodological tool for definition and interpretation of social categorizations, and on the other to stress the fact of the continuing presence, as well as steady augmentation in size and importance, of the working class. In this context we will first refer to the views which either posit a diminution in the significance of social class, as far as social reality is concerned, or generally question its usefulness as an analytical tool. We shall then try to deal with the problem of definition of classes by criticizing the theories which, although included among those of Marxist thought, adopt a restrictive framework in establishing the dimensions of the working class. We shall subsequently attempt to determine the size of the social classes in a series of developed countries and finally endeavour to explain why the working class, in spite of constituting numerically the largest social class, has not succeed in acquiring political power.

2. Towards the end of social classes?

Within the framework of the general theory of social classes, we can divide the theories into two broad categories, formulated at different times, which cast doubt on the significance of the Marxist approach to social classes. The first includes a standard argumentation which came very much into prominence during the period from the end of the 50s to the 80s. According to this theoretical current:

a) There exists not a single dominant class but certain groups charged with the conduct and administration of specific social fields. This may be attributed to the absence of an economically dominant stratum that has succeded in gaining control of the functions of the State. Division of powers leads to a segmentation of the sources of power, so that no social class can be the dominant one in society. The ever-deeper implantation, in other words, of democratic institutions, has resulted in a weakening of special power that each class, taken separately, used to possess (Andréanni/ Féray 1993, 225).

b) Earlier economic distinctions have been effaced at the same time that many-sided economic transformations are to be noted: division of economic power into that possessed by the proprietors and that of the managers, dispersal of professional specializations among salaried employees, equalization of working time, improvement in living standards, changes in working conditions, establishment of progressive taxation, increase in social mobility.

c) Transformation of capitalist society leads to transformation of the two basic opposing classes and formation of a plethora of indeterminate social groupings. This is explicable as a side effect of "tertiarization" of the economy, the emergence of a technically specialised workforce and improvement in incomes (Andréanni/ Féray 1993, 226).

d) Last but not least a growing mood of individualism (Andréanni/ Féray 1993, 225-6) [1] is also to be detected.

As far as the second category is concerned, in recent years some theoretical approaches have developed which go so far as to speak even of the death of social classes. The reasoning behind these theories is very simple, so much so that it could even be characterised as simplistic: there is a gradual diminution in economic differences and educational inequalities, a generalized social mobility and a segmentation of common practices which in the past used to characterize individuals belonging to the same socio-economic categories. The result is a dissociation of professional from class consciousness. R. Saunders underlines the importance of the spread of ownership in this development (Saunders 1995, 99). According to J. Pakulski the notion of social class has lost the special distinction that characterised it in the past as the key to sociological theory (Pakulski 1993, 289). Clark and Lipset conclude that new models of social stratification have appeared which are so different from their counterparts of the past that it is possible to speak of a fragmenting of social stratification in the traditional sense. This development is due: a) to the discrediting of economic determinism and the greater weight assigned to social and cultural factors b) to the strengthening of forms of political practice derived from other groupings, distinct from social classses, at the same time as a retreat is visible from the practices of class politics c) to the weakening of family ties d) to the fact that social mobility is determined to a much lesser extent by the social status of the family and is increasingly contingent on the personal abilities of each individual and his/her level of education (Clark- Lipset 1991, 407-8).

Class analysis suffers from an observable inability to interpret political and social processes precisely because of the collapse of the old hierarchies and the fragmenting of social stratification. The system of stratification in the developed countries has become more pluralistic and multi-dimensional, coming under the influence of factors that are external to labour. The evident result of these changes is the reduced weight of class differentiations, first and foremost those deriving from the ideology that classifies people as right and left, and the emergence of a politics embracing multiple distinctions - a far cry from the outdated categorization into social classes (Clark- Lipset- Rempel 1993, 293) [2].

The two theoretical currents have much in common but there are also notable differences between them. The basic element of agreement is their certainty concerning the diminishing importance, perhaps to the point of disappearance, of the Marxist conception of social classes. The greatest disagreement has to do with the varying weight assigned to extra-economic factors.

The second category undoubtedly includes the historically more recently-formulated theories which have been influenced by philosophical currents propounding analytic schemata such as “the end of history” or “modernity” and “post-modernity”, “neo-liberalism”, etc. By contrast, the views included in the first category, chronologically prior to the latter, were formulated in periods characterised by economic development and citizen participation in politics. It is therefore logical that they should be of different content.

Whatever the case, the general conclusion emerging from all these theories casting doubt on the utility of the Marxist conception of social classes is that in our day an objective contraction is to be observed in the numerical size of the working class while at the same time there has been a weakening of the material relationship between members of the same social class. The consequence of this has been class pacification of society, the retreat of social movements, the disappearance of revolutionary theory and subversive parties, the emergence of special-interest activism and individualism in the ideology and practice of the working people.

This article serves a twofold purpose: the primary objective is to map the basic contours of the social classes in our day. The position we propose to adopt is that the changes which have taken place in productive processes have not brought any substantial alteration to the primacy, both quantitatively and qualitatively, of the working class in the division of labour. It goes without saying that argumentation in support of such a view must draw on prior theoretical and empirical analysis.

In this perspective the identity of the working class is indissolubly linked both with the process of capitalist production as a whole and with the circulation of capital. This thesis leads us to the necessity of examining the way in which the transformation of capital is a unified process, which means that it is wrong to make the division between the three spheres of production (industry, commerce, services) a criterion for inclusion in a social class. Just as there are members of the working class employed in industry, there are also members of the working class in commerce or in the service sector. The Marxist definition of social classes is unrelated to the specific forms assumed by the circulation of capital, and with the ways in which extraction of surplus value is effected. For Marxist theory the basic criterion for social stratification is firstly the individual's relationship to the means of production and secondly the quantity of social wealth he possesses and his position in the social division of labour. Extension of the so- called “services” sector does not in any way affect this basic theoretical standpoint.

The second aspect of this essay involves the attempt to answer another question connected in the most general sense with the theory of social classes: how is it that the working class, despite the fact that it is numerically the largest social class and the most important one from the viewpoint of its place in production, still remains a dominated and exploited class? We will try, in other words, to pinpoint the factors that have led to diminution of the influence of trade unions, predominance of bourgeois ideology within the parties of the left and political failure of the labour parties.

3. The unified process of the circulation of capital

The greatest problem of the theory of social classes has to do with the question of people working in commerce - in our opinion with all those employed in the so-called “tertiary” sector of production. For almost 30 years now a discussion has been underway concerning the class position of working people who do not produce surplus value. N. Poulantzas, among others who confuse the production of surplus value with productive labour [3], judges that the heart of the capitalist system is the production of surplus value, so that this form of production is the decisive factor for dividing society into classes [4].

Poulantzas's position suffers from two weaknesses in this respect. The first is the reductionism whereby the working class as a whole is identified with productive workers and excluded from the category of non-productive workers. “The working class” thus appears as a concept derived from another concept, that of productive labour. By contrast, as Resnick/ Wolff observe, it would more appropriate to define the working class as a particular social grouping acting within a capitalist social formation (Resnick/ Wolff 1982, 9), which implies the need to analyse the particular social conditions that led to its formation, without finding it necessary to import ancillary concepts. The second error N. Poulantzas commits is to conceive of the aim of production under capitalism as creation of capitalist commodities, the value of which is expressed partly in the surplus value produced. But the question is not one of producing commodities but of realizing surplus value or profit (Nagels 1974, 131), through a uniform capitalist process (Berthoud 1974, 102). If the products do not reach the market and are not sold, neither will profit will be realized nor will self-reproduction of capital take place, as the merchant-capitalist will not again order commodities from the manufacturer-capitalist.

In its simplest form, capital circulates through three phases. In the first phase the owner of capital acts as a buyer in the commodities market (which commodities include labour power). In the second phase he acts as organiser of production and in the third he appears in the market as a seller [6]. Value assumes a different material form in each phase: in the first money, in the second the productive process, in the third the material commodity [7]. The circulation of capital presupposes that these successive transformations are implemented with no loss of value at all. The transformations occur automatically, passing through the different phases at distinct places and times (Harvey 1984, 83). What is involved essentially is a second level of analysis that Marx carries out in Capital, from the moment that he demolishes the conceits of vulgar classical Political Economy vis à vis the exchange of equivalents (wages-labour) and the interpretation of profit as a form of “reward” for capital, or the various sources from which income is distributed to different classes, transposing his analysis to the real conditions of production (exploitation, surplus value, accumulation). At this level it can be ascertained that the structure of capitalist production is a complex process in which production and circulation are linked (Cutler- Hindess- Hirst- Huissain 1997, 148).

All these problems have their origin in Marx assigning a dual sense to the term “circulation”. By circulation we understand the movement of capital from one phase to another, one such being the sphere of circulation, which covers the period of time when a finished commodity is on the market seeking to become an object of exchange. The circulation of capital can thus become comprehensible in the following way: Surplus-value is created in production and realised through circulation. Despite the fact that the crowning point of the process is that of production, capital which does not manage to pass the test of circulation is no longer capital. Marx defines the realization of capital in terms of the successful movement of capital through each one of the previously mentioned phases [8]. Money capital must be realized through production, productive capital must be realized through transformation into the commodity form, and commodities must be realized by assuming the form of money. This realization is not consummated automatically, owing to the fact that the phases of circulation of capital are separated in space and time (Harvey 1984, 84).

In order to render comprehensible the importance of the function of the non- productive sector of capital circulation, it should be noted that following the outbreak of the economic crisis of 1973, a certain tightening of discipline was observable over the regulatory institutions and control procedures for circulation of capital (in particular those covering banking and the Stock Exchange). Nevertheless, these institutions and procedures, though non-productive in form, are included in the process of capital reproduction (Johnson 1977, 216-7), to the extent that it can even be claimed, albeit schematically, that there is a “symphysis” between the sphere of production and that of circulation (Palloix 1977, 108-9). Of course, these developments in no way cancel out the three different phases of the single capitalist process. On the contrary, they show the flexibility that characterises capital when it comes to increasing the rate of profit and the potential for incorporation of these phases into a single entity - namely that of monopoly capital.

In conclusion, it should be evident that production, distribution and circulation of commodity capital (again, bear in mind that money is also a commodity) are different moments in a single process whose aim is realization of surplus value. The production of commodities is merely the prevailing moment, which is, however, in a dialectical relationship with the others (Μαυρουδέας 1993, 73).

Marx is thus absolutely right to stress that “the direct aim of the capitalist production is not the production of the commodity but the production of surplus value or profit (in its developed form). Not the product but the surplus product. By the same token, labour is productive only if it produces profit or surplus product for capital” (Marx 1975, 653).

It is for this reason that Marx regards authors, teachers, actors and writers as productive working people, from the moment that they place their labour power at the service of capital. It is therefore obvious that what matters for the definition of productive labour are the relations of production into which the working person has been integrated and not the form, material or immaterial, which the product of this labour assumes. An author who works for a publisher is thus a productive worker, while a self-employed tailor is a non-productive worker (Nagels 1974, 38).

Perhaps the most significant part of our disagreement with N. Poulantzas has to do with the confusion this author creates when he uses the term “services”. It is one thing to use the term “service” to denote a form of exhange of the product of labour with money, and quite another of use it to mean a form of production of immaterial products (Colliot-Thélène 1975b, 97). Poulantzas seems to make the mistake of defining productive labour through its material content, as a result of the process of transformation of nature, whereas Marx focuses on the social form of labour, and above all on the relations of production, on the basis of which the productive process is put into operation (Bihr 1989, 47-8). Whether the form of the product is “material” or “immaterial” is neither here nor there. The important thing is that it should be transformed into a commodity and exchanged with the general equivalent (money) and that surplus value should be realised. What constitues the commodity in the transportation sector is neither the wagon nor the labour power of the engineer but the transportation itself (Bidet 1975-76, 54). As Resnick/Wolff correctly observe, it is very possible that the dynamics of capitalism, especially in the modern era, will even make it necessary for one capitalist company to purchase the commmodity of services from another capitalist company (Resnick/ Wolff 1982, 16- footnote 11). We might mention by way of example the supply of security services to banks and companies, the employment of teams of office cleaners, even foreign language lessons to enable company employees to upgrade their skills. The same thing exactly is involved in each case: it is as if the client companies were buying specific material products from the selling companies.

At the same time it is a matter of small importance if services are consumed in a productive or non-productive way (at the individual level). The peculiarity of “services” as opposed to material products is linked to the fact that their use value cannot be separated from their consumption (Bidet 1975-76, 54). This does not mean that their exchange value disappears in consumption in the same way. On the contrary, during the process Money-Commodity...Product-Money' the exchange value does not disappear. It is transformed into Money' (Bidet 1975-76, 54) and the accumulation of capital continues. According to J. Bidet, this “useful result” constitutes the commodity, from the moment that its exchange value “is defined by the quantity of the living and dead labour that the use of the means of production includes, and the value of which is realized by the process of the productive consumption of commodities itself” (Bidet 1975-76, 55). This position goes far beyond the case of transportation because it involves “services” as a whole, thus explaining why this sector constitutes a sphere of production of immaterial products from which the employer derives surplus value (Bidet 1975-76, 55). The salaried employees of a company providing “services” do not exchange their labour for the income of the clients but for “the reward they are given by their employers, which functions as capital, as employers do not pay unless they are sure that they will obtain from their employees more than they have given to them” (Colliot- Thélène 1975a, 40). From the moment that there exists a market for labour power and so unpaid labour, the phenomenon of exploitation makes its appearance.

4. On the definition of social classes

We have established that there is a continuity between the spheres of production which does not allow of the examining of each sphere individually. This means that members of the collective worker should be classified as a whole and not in accordance with the specifics of the particular aspect of production in which they are employed. From this viewpoint Lenin's celebrated definition is as pertinent as ever, assisting with clarification of the multi-faceted problem of defining social classes: “Classes are large groups of people which differ from each other by the place they occupy in a historically determined system of social production, by their relation (in most cases fixed and formulated in law) to the means of production, by their role in the social organization of labour, and, consequently, by the mode of acquisition and the dimension of the share of social wealth of which they dispose” (Lenin 1977, 13). We might note that in Lenin's definition there is a co-articulation of three criteria: a) position in relation to the means of production, b) position in the social division of labour, c) means of acquisition of - and level of - income (Bensaid 1995, 203).

The common denominator which traverses these three criteria in Lenin's definition is the phenomenon of exploitation. The possessor of the means of production exploits the person who possesses only his labour power, because he pays him less than the value of his labour. However, in order for this social relation derived from the possession of capital to be reproduced (after all this is why Marx claimed that capital is primarily a social relation) some structural characteristics must be shaped in the production process that will facilitate circulation of capital and create the hierarchical structures necessary for working discipline to become attainable. In this sense exploitation, and on a second plane relations of domination, but above all the way they are articulated into a social structure (Croix 1984, 94), are the agents in formation and reproduction of social classes.

The conclusion is thus that on the one hand the foundations of prevailing social arrangements are to be situated in the existence of relations of exploitation and domination, and on the other that membership in a particular class depends firstly on ownership of the means of production and secondly on position in the division of labour and the amount of social wealth that each person extracts.

Of course it should be stressed that classification of the various agents in social relations is no static and cerebral process. On the contrary, social classes are defined through an antagonistic relation, the class struggle (Balibar 1985, 174), which determines the movement of history. This means that the outcome of the class struggle brings about transformations in the positions of social categories and social strata in such a way that there is no one-to-one correspondence between assigned social class and membership in a particular professional category. Nothing is exempt from change.

With these general definitions as our starting point we proceed to some conclusions about the most significant characteristics of the bourgeois class [9]: it is the class that directs the capitalist productive process, the class that, always with a view to its own interests, defines the context and the hierarchies of the social praxis dominated by capital (Bihr 1989, 88-9). Its position is based on the ownership of the means of production and on subjection of society to its power. At a level of high abstraction its members are defined as non-productive exploiters/possessors/extractors of surplus labour-cum-organisers of the mechanisms of domination (Johnson 1977, 203).

The working class is deprived of possession of the means of production and performs all those practices that are aimed at furthering reproduction of capital and reinforcement of social power. It neither possesses control of nor is able to influence the context of its labour. It simply plays an executive role within the social division of labour (Bihr 1989, 90). In a more abstract away we could define the working class as consisting of exploited/non-possessors/producers/wage-earners enduring the constraints imposed by the mechanism of domination (Johnson 1977, 202-3).

Between the two fundamental classes there is also a third intermediary class: the petty-bourgeois class. This class includes all those who because of their position in the social division of labour have an income greater than the value of their labour power (Baudelot- Establet- Malemort 1973, 224). It is a class which is at once dominated by the bourgeois class and dominant over the proletariat (Bihr 1989, 89). In this sense we believe that the correct characterization of the petty-bourgeois class is to conceive it as an intermediary class, subordinated to the two fundamental classes (Resnick/ Wolff 1986, 102) and not to be equated with the middle class. Synonymous as these two terms may seem, in this specific case their referents are completely different. The term “middle” class implies an imaginary continuity in social stratification, a graded pyramid at the basis of which is situated the working class, in the middle the so-called middle strata and on the top the ruling class. By contrast the term “intermediary” denotes an intermediate social class, which is not economically exploited but functions in an ancillary capacity within the structures of economic exploitation. On the ideological plane it makes a decisive contribution to reproducing the fetishistic conceptions the ruled have of the conditions of their subordination. On the political plane it is characterized by an uncertainty about which one of the two fundamental classes it should be allied to.

The petty-bourgeois class is divided into two fractions: the new petty- bourgeois class and the traditional petty-bourgeois class. That both these fractions belong to the same class is evidenced by the way their social practices are characterised by inability to initiate autonomous political action - in contrast to the working class or the bourgeoisie - so that they perforce attach themselves either to the former or to the latter class; and on the other hand by their shared economic basis, deriving either from. extraction of surplus-value (traditional petty-bourgeois class) or from payment from the mass of surplus-value (strata of the new petty-bourgeoisie class employed in the secondary and tertiary sector), or from their pay being above the level of required for reproduction of labour power (cadres of the state bureaucracy, liberal professions). Their common denominator is members of this class not suffering exploitation, i.e. being paid for the total of their working time.

The traditional petty-bourgeois class thus includes all industrialists and merchants who do not achieve enlarged reproduction of their capital. The new petty-bourgeois class can be defined, and simultaneously distinguished from the traditional petty-bourgeois class, on the basis of the fact of non-possession of the means of production and non-extraction of surplus-value. It is definable at a secondary level through the in-between position it occupies within the process of production, where it suffers the political and ideological domination of the ruling class, being obliged to carry out the orders of its employers [10].

Its basic function is to activate and reproduce the relations of exploitation and domination engendered by the capital/labour relation. This is achieved through segmentation of the functions pertaining to strata belonging to the new petty-bourgeois class in a way analogous to the segmentation of capital into class fractions (Bihr 1989, 174).

This fraction thus includes all those who, whether working as liberal professionals or as salaried employees, have been allotted the task of supervising and organising the work system (technicians, engineers, lawyers, etc), monitoring the coherence of capitalist operations (lower and middle-ranking functionaries within the mechanisms of repression), or, finally, legalising the conditions of reproduction of existing social relations (judges, middle-ranking officials, lower echelons of intellectuals).

Liberal professionals do not belong in the working class because they are paid for a period of time longer than that during which they work (Baudelot-Estable- Malemort 1973. 224-33). But neither do they belong to the bourgeois class because they do not own the means of production. They belong to the petty-bourgeoisie because they participate in functions by means of which capital secures the conditions for smooth operation of the production process (organization and supervising); functions, the framework of which have been decided on and designed by higher administrative cadres [11].

5). The extension of productive activities [12]

The basic thesis of this essay is that because of the enlargement of the fields of action of capital, the working class is increasing in size. The reason for this is that workers are to be found in the sectors of services and commerce as well as in industry - we have already explained why we consider the majority of working people in commerce to be part of the working class (Andréanni/ Féray 1993, 235). The two most important reasons for increase in the size of the working class are extension of economic activities into new sectors (microelectronics, computer science, biotechnology, telecommunications, marketing, advertising) and the industrialization of services.

Our view is that, notwithstanding the theories to the contrary that postulate “tertiarization” of the economy and “petty bourgeoisification” of the working class, capitalist exploitation does not have to do with the material form of the use value produced but with the social conditions within which it is produced. From the moment that labour is exchanged for variable capital, the capitalist commodity forms a social relationship on the basis of whatever the use value might happen to be. In this way innumerable “services” assume the form of capitalist commodities, a development signifying a broadening of the working class through addition of new categories of worker [13].

In conclusion, the development of employment in the tertiary sector is in essence the result of the development of productive forces and the extension of capitalism into new fields of activity. New fractions are thus created within the working class linked to the various stages in the production process (Harnacker 1974, 160, Colliot-Thélène 1975b, 102). The new strata of employees have lost all the traits clearly distinguishing them from industrial workers (Braverman 1974, 355, Gorz 1974, 1160). Various empirical studies that have been carried out indicate that these employees perform monotonous, rule-dominated, de-specialized work, subject to constant controls [14], to the extent that the whole of the working space in which they are employed takes on the social characteristics of a factory [15].

One fact serving to corroborate the above is that during the '80s and '90s capital extended its activities into sectors which had hitherto remained beyond off-limits for exploitation: health, education, welfare, free time, etc. Previously it had been the State that had undertaken the cost of these activities because of their low level of profitability. The result was to be incorporation of numerous social strata into the process of private production and the corresponding extraction of surplus-value. In the same way one may observe the development of capitalistic structures in sectors that had previously yielded profits for the traditional petty-bourgeoisie (repairs, renovations, plumbing). Finally there was a strengthening of the processes of real submission of labour to capital in the sectors of agriculture (an increase in the tendency towards salarification and capitalization [16]), transport [17] and commerce (concentration and centralization [18], proletarianisation of the ruined petty-bourgeois strata, decrease in the number of grocers’ shops, increase in the number of supermarkets).

6. Concerning the condition of the modern working class.

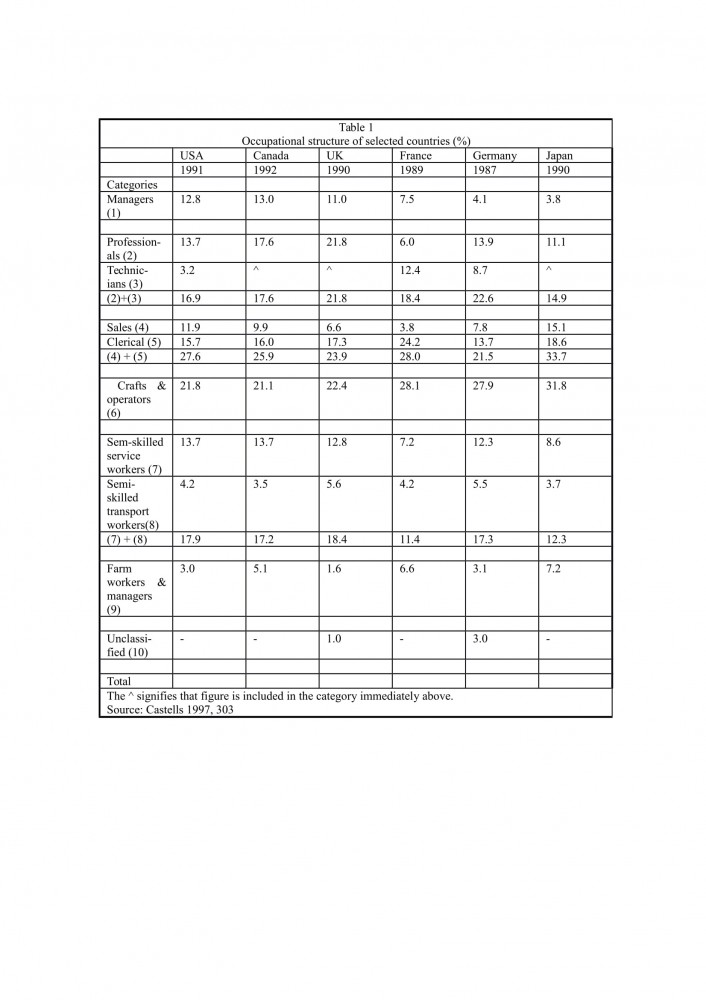

In order to clarify the evolutionary trends in the working class as was a whole as well as in the corresponding constituent parts, we utilised the statistical service empirical data from different countries cited by M. Castells. It is obvious that our conclusions are of a descriptive character but in any case they give some indication of the social developments and transformations of the working strata in the broadest sense.

From Table 1, which presents the occupational structure in the 6 most developed countries in the world, the following conclusions emerge:

In the USA the bourgeois class constitutes the 12.8% of the active population who are managers and a part of the 3.0% of farm workers who are in managerial positions. Nevertheless its total size, however calculated, does not exceed 15% of the economically active population. The petty-bourgeois class, consisting in the first instance of the sum total of professionals and technicians, accounts for around 17%. Finally, the working class, which is made up of wage-earners in commerce, salaried employees, technicians and operators, semi-skilled workers in the service sector and a section of the farm workers, accounts for 65% of the active population.

Employing the same method, we may conclude that in Canada the bourgeois class makes up around 16-17%, the petty-bourgeois class between 18% and 20% and the working class between 60% and 65% of the active population.

In the United Kingdom the bourgeois class accounts for between 12% and 14% of the active population, the petty- bourgeois class from 20% up to 22% and the working class from 65% to 70%.

In France, the size of the bourgeoise class is between 7% and 11%, that of the petty-bourgeois class from 20% to 22%, and that of the working class from to 65% to 70%.

In Germany, the bourgeois class accounts for between 4% and 6%, the petty bourgeois class from 23% to 26% and the working class from 62% to 65%.

Finally in Japan, the bourgeois class constitutes 4% to 8% of the economically active population, the petty- bourgeois class from 16% to 19% and the working class from 73% to 77%.

The final conclusion that emerges is that in none of the developed countries does the bourgeois class exceed 17% of the economically active population and the petty-bourgeois class 26%, while at the same time the working classes accounts for between 73% and 77%.

At this point our analysis could be deemed complete. We showed that notwithstanding theories of “petty-bourgeoisification” of the working class, the elements of exploitation and domination remain capable of explaining the division of society into classes, and of corroborating the enlarged size of the working class. However, what remains is to answer the second question we posed in the introduction to this article: why the working class, in spite of being the most numerous class in society has not succeeded in transforming itself into the dominant class. We shall deal with this issue in the last part of our essay.

7) Why did the working class eventually lose the game?

The problem that arises has to do with the factors that have led to a by-now familiar outcome: despite its size as a proportion of the active population the working-class has lost, albeit temporarily (?), the political game. Of course, the constraints of this article are too narrow for us to be able to deal with this extremely broad issue. Consequently our report will be brief and schematic.

In essence, this question links the numerical size of the working class with its access to [T1] political power. From a strictly Marxist viewpoint perhaps it makes no sense at all, for reasons which we will explain below. Nevertheless, we believe that it is a reasonable question which frequently is posed by the supporters of theories of pluralism, and that is why it demands an answer. In a sense the problem started from the moment that suffrage was massively extended in the liberal republics of the 19th century. At that time the real issue under dispute was the means by which this extension would be achieved without the consequent participation of the working strata in the electoral processes resulting in a parliamentary overturn of the capitalist system (Macpherson 1985). The eventual democratic resolution of this issue, whereby through the existence of multiple options the electorate is able to designate the political agency of its choice, testifies to the ability of pluralistic democratic regimes to withstand the shocks brought about by free political competition (Dahl 1976). Consequently, even accepting the presence of a numerically large working class in no way precludes a potential electoral victory by a party that will express the interests of the working class in a future electoral contest. Besides, as Fukuyama maintains, universalisation of the western model of liberal democracy is the last stage of ideological evolution of the human race (Fukuyama 1992).

This coherent theoretical model is faced with two kinds of objections: the first has to do with the overall functioning of the capitalist system and the second with the transformations in the functions of the State that were brought about by generalisation of the suffrage; both of them on account of their very structure serve to foster reproduction of the prevailing social model and inhibit any attempt to go beyond it.

More specifically, as far as the former issue is concerned, it cannot be separated from fundamental principles of class domination, which are to be derived from the interaction of three elements: control over the process of production (economic element), the structurally capitalist character of the machinery of state (political element) and correspondingly capitalist character of the dominant ideology (ideological element). The existence of these fundamental structures is conducive to the ability of the bourgeois class rule, even though, as far as population is concerned, it forms a minority.

Otherwise expressed, in “normal” (for capitalism) conditions, it is the bourgeois class that rules, precisely because of the existence of the above-mentioned elements, which result in the formation and reproduction of three kinds of fundamental inequalities. The first form of inequality is economic inequality, deriving from the following reality: through its possession and control of the means of production and the production process, the bourgeois class is able to pay the working class less than the real value of its labour time. It thus exploits the latter. The surplus labour for which the working class does not get paid forms the basis for the material reproduction of the bourgeois class. However, the more the working class fails to transform itself from a class in itself to a class for itself, the more necessary will it be for its reproduction that it be incorporated into the capitalist process.

The second form of inequality is political inequality based on the fact that the bourgeois state is the result of class struggle within a social formation where the capitalist mode of production predominates. This is however a result with specific structural limits conditioned by its basic raison d’ être, which is to ensure the long-term interests of the bourgeois class. For this function of the state it is indispensable that mechanisms of repression and consensus be brought into operation. These mechanisms are the means of political domination by which the bourgeois class imposes its rule on the dominated classes. A basic element in these mechanisms of domination is the establishment of the right of universal suffrage, by means of which the exploited classes are co-opted, since it is through their participation that they are “obliged” to accept the final result of a process which is distinguished by the – objectively real – fact of formal equality at the election, concealing the – equally real – fact of a prior process of political influence that is particularly unequal (Miliband 1973). The final result is the formation and reproduction of one more level of inequality, buttressing bourgeois power.

The third form of inequality is ideological inequality, or, more properly, the ideological hegemony of bourgeois attitudes towards the spontaneously anticapitalist reactions of the working strata. This is a multi-faceted process which a) on the one hand rests on the functioning of the Ideological Mechanisms of the State (Althusser 1976), whereby an attempt is made to persuade the dominated classes of the rightness of bourgeois positions presented behind the veil of the national/general interest[T2] , the aim being that the citizen should respond positively to these messages, assimilating them and articulating them as his own interests and needs; b) on the other hand, an important role in the processes of hiding the relations of class exploitation and domination is played by the mechanisms of concealment, which function at an economic as well as at an institutional level. At the economic level, this process takes the form of commodity fetishism (Marx 1978), in accordance with which capitalist processes are taken for neutral and technical processes, and wages for the fair equivalent of a specific amount of labour-time, while at the institutional level mechanisms of concealment are constructed (i) around constitutional equality (Anderson 1976), whereby all citizens are considered equal despite the evident economic, political and social inequalities characterising relations between them, and (ii) around social mobility - a mechanism which offers the hope of a better future to every scion of the working class, concealing the reality that the needs of reproduction of the system demand only a limited number of people to staff the positions higher up the ladder.

These three inequalities (economic, political, ideological) preserve and reproduce the relations of domination that exist between the bourgeoise and the working class, irrespective of the numerical strength or weakness of each class. At the same time, the universalisation of the suffrage, the second issue we raised initially, created the need for today’s more specialised measures for protection of the social system, above and beyond the system’s general functioning. Thus the possibility of a political overturn through parliament was itself overturned through a process of gradual displacement of powers from the unpredictable parliament to the executive and from the unstable executive, because of its dependence on the political mood of the parliament, to the bureaucratic mechanisms of public administration. There is nothing accidental about this displacement from the executive to the administration. The latter, precisely because of its bureaucratic structure, has succeeded in acquiring a flexibility very conducive to a sealing-off of its mechanisms from public scrutiny. Basic functional components of the administration such as secrecy, institutional anonymity, decentralisation of authority, all exert a decisive influence in the direction of diffusion of power and its recomposition for the purpose of implementing basic bourgeois strategies (Φεραγιόλι 1985).

A brief reference has already been made to the mechanisms by means of which the ruling class seeks and achieves domination over the working class. One more issue yet to be clarified has to do with the attitude of the working class towards the power of capital and its strategy for confronting it, at any rate since the time of the Bolshevik Revolution. It is necessary to understand, in short, why the working class has not managed to develop anti-capitalist practices of such a kind that through exploitation of its crucial role in the process of production as well as its demographic strength, it could draw seriously into question the existing system of exploitation and domination.

Let us start from the beginning. The most serious weaknesses of the working class – in reality of its political representatives - have to do on the one hand with attitudes to the importance of changes in the production processes and on the other with one’s orientation to the character of the State.

In the period before World War II, the general strengthening of forms of relative surplus-value brought about multiple changes to the economic structure: an increase in the degree of concentration and centralisation of capital, intensified mechanisation of production, segmentation of the productive process, strict control of the pace of production. This was to result in an increase in productivity and thus an increase in the ability of capital to consent to a relative increase in wage levels. This had two consequences:

a) On the one hand the workers’ movement centred its strategy on the demand to increase its income [19] and not on the effort to bring about a modification in the relations of production (Ιωακείμογλου 1990, 31), so that the method of organisation of labour, perceived as something neutral and technical, remained beyond criticism (Andréanni/ Féray 1993, 272). What was involved were forms of intervention and interpretations of the present conjuncture that were very much under the influence of economism – an important species of deviation from Marxism. This was a logic with its origins in an inability to conceptualise certain aspects of social reality economic, political, ideological) as crucial class struggle issues.

What resulted from the above was a failure to understand how capital constitutes first and foremost a social relation, with the consequent emergence of a belief that the coming depression (that of 1929) would be disastrous for capitalism, leading inevitably to its downfall. There was no comprehension of the crisis as a specific conjuncture in the class struggle. On the contrary, it was seen as marking the limits of the capitalist mode of production. In this way capital’s capacity to recover its powers was overlooked. The multi-faceted process of class struggle was essentially reduced to a simplistic equation: a rise in working class struggles posing economic demands + the catastrophic consequences of capitalist accumulation = social revolution.

The development of the class struggle in the course of the war, with a strengthening of the Communist-oriented partisan movement, and in the post-war period, resulted in a strengthening of the working class, with popular mobilisations at a higher level than in the years preceding the war. But the weakness of the workers’ movement, which had also been visible in the preceding period [20], merely intensified.

The result was that elements of bourgeois strategy made their appearance within Communist policies. Thus the rapid pace of development which characterised this period, whose significance had initially been underrated (in the thesis of a general protracted crisis) were subsequently regarded not as an expression of the bourgeoisie’s capacity to readjust the correlation of forces in the process of production but as something neutral and in fact desirable, constituting a foundation for the construction of socialism. The consequences of this reasoning was once more the displacement of conflict to the easiest terrain, that of the redistribution of income, rather than struggle at the level of the relations of production.

b) On the other hand the question of the State and its mechanisms were to be approached in a similar way. Inability to come into conflict with the machinery of State was to be transformed into “neutralisation” of the State’s operations. The State came to be regarded as a network of neutral instrumentalities whose class character consisted in the presence of the bourgeoisie at the head of it. This meant seeing the State as the vehicle which could conduct one through the transition to socialism [21], with the question of workers’ power taking the form of governmental power and proletarian strategy limiting itself to preparation of the party for parliamentary elections.

The result of this politics was to be for “governmentalism” to become the quintessence of the reformed labour parties. The party calls on the people to back its entry into the corridors of governmental power so as to extend democratic support to the demands of the working classes (Ιωακείμογλου 1990, 28). Gradually the Communist parties come more and more to resemble the “other” parties. What is different about them has to do with the relationship of representation they retain with the popular masses. Their statification entails submission to the image of politics imposed by the state through the prism of the dominant ideology (Τσεκούρας 1987, 24-5). Predominant in the discourses of the Communist parties are the forms of bourgeois democracy, which tend to substitute for working-class interests the demands, real or imagined, or public opinion, and political intervention through electoral marketing. The mapping out of autonomous class policy is replaced by an attempt to combine vague empiricism with a subservient species of realism. At the same time, instead of being made an issue of working-class hegemony, the issue of alliances and the extraction of the working and popular masses from the hegemony of the bourgeoisie is posed as an issue of alliance with the social-democratic parties, inside which, in a vague way, the Communist party would seek to undermine bourgeois influence. Much more than this, the retreat of proletarian hegemony in the politico-theoretical practice of these parties will be intensified both by the ideological influence of allied strata and divisions within the working class. This is linked on the one hand to incorporation of traditional petty-bourgeois strategies in the “transitional” programmes and on the other to the specific weight of the new petty-bourgeoisie. At the same time a combination of the registration of limits to the political infuence of the Communist parties and the contracting of alliances on the basis of a numbers-counting logic, along with a downplaying of the manner in which the ruling coalition is brought together and the conception of the State as a tool of the ruling fraction of the monopolies, will lead to the notorious “antimonopolistic alliance”, which will include even sections of the non-monopolistic bourgeois class.

Finally, the combination of economism, wheeler-dealing, electoralism and a a mechanistic-aggregative mentality that has become imprinted on the Communist movement essentially on the terrain of bourgeois hegemony will crystallise in a significant displacement in relation to the transition strategy whereby instead of the strategy of breach, a stages strategy is prescribed (antimonopolistic change initially, then socialism) under which the first phase will essentially mark the consummation of (capitalist) development and following that there will be socialist transition in a linear fashion, wherein the decisive element will be not radical transformations in the relations of production but development of the productive forces and public sector growth.

Undoubtedly in today’s conjuncture, which means in the period of the rise of neo-liberalism and the downturn in social struggles, the problems that the working class has to face are of a very different character. The crisis of overaccumulation that dates back to 1973 had the effect of lowing the rate of profit, to which employers reacted by endeavouring to increase their share of total income, using a host of different measures: austerity policies, part-time employment, flexibility, decrease in labour costs (Sakellaropoulos 1999, 338).

On the ideological level, this endeavour takes the form of a disintegrative individualism, even further limiting the possibilities for working class reaction. This is a development with roots in a multitude of different factors: 1) The growing problem of unemployment. As Andréanni/ Féray observe, in the face of the enormity of the problem “the logic of ‘looking after number one’ seems to prevail over all others” (Andréanni/ Féray 1993, 262). The moreso insofar as unemployment does not affect all categories of wage earner to the same extent [22]. 2) In a logic of sectionalism buttressed by the reality of unequal reward among the different sections of the working class. 3) In a loss of credibility on the part of the trade unions owing to their inability to win wage increases during economic recession (Andréanni 1993, 272) given their habit until recently of pursuing policies of partnership in enterprise management. 4) In their perennial insistence in uncritically accepting a model of workplace organisation at the shop floor level which will lead to unions continually being caught unawares in the face of rapid changes in production processes [23].

And the parties of the Left? Andréanni/ Féray give an excellent description of the general problem.

“They are condemned to marginalisation if they don’t break with the outlook and the policies they have had for the last fifty years. Playing in various ways the game of the Keynesian state, they believed that the solution to the social problem was to be found at the level of the State, which they had to influence, to invest, to conquer. When the limits of the State and the social reconciliation that it represented became clear, they found themselves at a loss. And this becomes even worse when some ‘labour’ parties become converts to the ‘realism’ of neo-liberal policies” (Andréanni/ Féray 1993, 274).

I thank R. Barns, S. Kouvelakis and P. Sotiris for their useful remarks on the content of this text.

Endnotes

1)See also a) Nisbet, R.1959. The Decline and Fall of Social Class. Pacific Sociοlogical Review vol. 2 (1): 11-28 b) Berle A. and G. Means. 1967. The Modern Corporation and Private Property. New York: Harcourt, c) Burnham, J., 1967. The Managerial Revolution, New York: Doubleday. d) Perkin, H. 1989. The Rise of Professional Society. Routledge: London e) Bell D. 1976. The coming of Post-Industrial Society. New York: Basic/Harper Torchbook.

2) For a comprehensive presentation of the theories that announce the end of the Marxist analysis of classes see the work by Pakulksi, J. and M. Waters. 1996. The Death of Class, London: Sage Publications. What should be made clear is that the present text does not aim at setting out specific counter-arguments to these views. Cognizant of the limitations as to what can be said in an article, we are interested in the first instance in recording the basic points of the Marxist theory of social classes, above and beyond the specific criticisms of it that might happen to be made. Anyone interested in reading some significant critiques of neo-liberal approaches to social class can consult: a) Chauvel, L. 1999. Classes et générations. L΄Insuffisance des hypothèses de la théorie de la fin des classes sociales. Actuel Marx no. 26 : 37- 52. b) Wright, E.O.1996. The continuing relevance of class analysis- Comments. Theory and Society vol 25 (5): 693- 716 c) J. Manza/ C. Brooks. 1996. Does class analysis still have anything to contribute to the study of politics? Comments. Theory and Society vol 25 (5): 717- 724. d) Marshall, G. 1991. In Defence of Class Analysis: A Comment on R. E. Pahl. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research no. 15: 114- 118 e) Hoot M., C. Brooks and J. Manza. 1993. The Persistence of Classes in Post-Industrial Societies. International Sociology vol. 8 (3): 259- 278.

3) See Nicolaus M. 1967. Proletariat and Middle Class in Marx, Studies on the Left no. 7 and Urry, J. 1973. Towards a Structural Theory of the Middle Class. Acta Sociologica vol. 16 (3), as cited by E. O. Wright. 1980. Varieties of Marxist Conceptions of Class Structure. Politics & Society, Vol 9 (3): 323- 370.

4) N. Poulantzas upholds the view that the working class is defined “by productive labour, which under capitalism means labour that directly produces surplus- value” (Poulantzas 1979, 94).

5) As D. Bensaid observes “In its crazy course, capital jumps from the one transformation to another with the vitality of a triathlist” (Bensaid 1995, 95).

6) The thesis of Marx is revealing:

“Capital as a whole, then, exists simultaneously, spatially side by side, in its different phases. But every part passes constantly and successively from one phase, from one functional form, into the next and thus functions in all of them in turn. Its forms are hence fluid and their simultaneousness is brought about by their succession. Every form follows another and precedes it, so that the return of one capital part to a certain form is necessitated by the return of the other part to some other form. Every part describes continuously its own cycle, but it is always another part of capital which exists in this form, and these special cycles form only simultaneous and successive elements of the aggregate process.

The continuity -- instead of the above-described interruption -- of the aggregate process is achieved only in the unity of the three circuits. The aggregate social capital always has this continuity and its process always exhibits the unity of the three circuits”

(Marx 1885).

And later on:

“The two forms that the capital value assumes within its circulation stages are those of money capital and commodity capital; the form pertaining to the production stage is that of productive capital. The capital that assumes these forms in the course of its overall circulation, discards them again and fulfils in each of them its appropriate function, is industrial capital - industrial here in the sense that it encompasses every branch of production that is pursued on a capital basis.

Money capital, commodity capital and productive capital thus do not denote independent varieties of capital, whose functions constitute the content of branches of business that are independent and separate from one another. They are simply particular functional forms of industrial capital, which takes on all three forms in turn. The circulation of capital proceeds normally only as long as its various phases pass into each other without delay. If capital comes to a standstill in the first phase, M-C, money capital forms into a hoard; if this happens in the production phase, the means of production cease to function, and labour- power remains unoccupied; if in the last phase, C'-M', unsaleable stocks of commodities obstruct the flow of circulation.

It lies in the nature of the case, however, that circulation itself dictates that capital is tied up for certain intervals in the particular sections of the cycle. In each of its phases industrial capital is tied to a specific form, as money capital, productive capital or commodity capital. Only after it has fulfilled the function corresponding to the particular form it is in does it receive the form in which it can enter a new phase of transformation”

(Marx 1978, 133).

According to G. Labica “to the three stages correspond three forms and, at the same time, three functions of capital. Money capital has the function of creating the conditions that will make possible the union of means of production and the workforce, productive capital has the function of creating surplus value, commodity capital has the function of realizing this increasing capital value which, consisting of the developed value and the surplus value, will be placed in circulation again” (Labica 1985, 168).

7) As Harvey observes, the realization of capital is defined in terms of its succesful movement in all three phases. Money capital is realized in the process of production, productive capital is realized in the form of the commodity and commodities are realized in the form of money (Harvey 1984, 84).

8) Marx claims that:

“Without production, no consumption; but also, without consumption, no production; since production would then be purposeless. Consumption produces production... because a product becomes a real product only by being consumed. For example, a garment becomes a real garment only in the act of being worn; a house where no one lives is in fact not a real house; thus a product, unlike a mere natural object, proves itself to be, becomes, a product only through consumption”

(Marx 1973, 91).

And later on

“Circulation - as the realization of exchange values - implies: (1) that my product is a product only in so far as it is for others; hence suspended singularity, generality; (2) that it is a product for me only in so far as it has been alienated, has become for others; (3) that it is for the other only in so far as he himself alienates his product; which already implies (4) that production is not an end in itself for me, but a means”

(Marx 1973, 196).

9) Within the framework of this article is not possible to deal in detail with the theory of social classes, as expressed by the current of so-called analytical Marxism. Very briefly, analytical Marxism emphasises the importance of the reproductive process, at the same time downplaying the significance of ownership or control of the means of production in defining social classes. Analytical Marxists are more interested in power derived from mastery of individual skills, natural capitals, the organization of productive resources. In addition to this, the special case of the theory of E.O. Wright on “contradictory class locations” presents the problem of non-recognition of the petite-bourgeois class as a class with special characteristics, proposing its replacement by the vague concept of contradictory locations. As for the discussion concerning the theory of analytical Marxism, see among others: 1) Andréanni T. and M. Féray. 1993. Discours…. 2) Actuel Marx 1990, no 7: Le marxisme analytique anglosaxon 3) Wright E.O 1993. Class, Crisis and the State. London/ New York: Verso 4) Carchedi, G. 1986. Two models of class analysis. Capital and Class no 29: 195- 215, 5) Roemer, J. 1982. New Directions in the Marxian Theory of Exploitation and Class. Politics and Society vol. 11 (3): 253- 287.

10) Carchedi regards it as an additional characteristic that members of the petty-bourgeoisie simultaneously perform functions of capital and of the collective worker (Carchedi 1977, 88-90). But this does not seem to be correct, because functions of capital are performed only by members of the bourgeois class, while all workers from the industrial worker up to the qualified engineer participate in “the collective worker”. On the issue of the collective worker, see K. Marx 1974, 480-1. For a very interesting critique of the views of Carchedi see A. Cottrell 1984: 84-8.

11) Of course, it should be made clear that the new petty-bourgeois class does not form a coherent social stratum. According to Andréanni/ Féray excellent analysis, this class can be divided into two categories: the higher petty-bourgeois class and the lower petty-bourgeois class. The former includes administrative and commercial employees in companies as well as engineers and technical cadre. The latter includes middle-ranking administrative and commercial employees, technicians, foremen and supervisors. In the same way, within each category there are distinctions to be drawn. Andréanni/ Féray emphasise that the higher petty-bourgeois class can be divided into two subcategories: the higher petty-bourgeois class of executives, and the higher petty-bourgeois class of intellectuals. The former category includes all those who exercise the functions of designing and administering the development and production processes. The latter includes all those who exercise the functions of designing and administering materials, products and techniques related to the labour process and labour productivity. In the same way the lower petty-bourgeois class can be subdivided into cadres and intellectuals. The former includes mainly foremen and supervisors. The latter includes, in the first instance, technicians (Andréanni/ Féray 1993, 254-5). Of particular significance is likewise the analysis of Resnick/ Wolff, who discover that it is sterile to insist on the existence of two fundamental classes, as many Marxists do. (Yet Marx in Capital when referring to two fundamental social classes explains that he does this because he is moving at the highest level of abstraction, the level of an “ideal-typical” capitalism, meaning that in concrete historical formations the situation appears different, as more than two classes exist. In any case, the greatest problem that left revolutionary movements had to face was that of the petty-bourgeois class.) They maintain that apart from the bourgeoisie and the working class there is another type of class, the subsumed class. Subsumed classes include all those individuals who neither contribute nor extract surplus-labour. Their occupation involves the performance of some special social functions, and they sustain themselves through mechanisms of distribution of part of the extracted surplus-value. This is accomplished either through direct payment by the agents of capital (in the private sector of production), or through taxation (in the public sector). What makes the contribution of Resnick/ Wolff especially useful is the fact they do not consider the subsumed classes “parasitical” and condemned to disappear as a remnant of an older mode of production. On the contrary, the overall functioning of the capitalist system and the demands that arise from that functioning make these classes absolutely indispensable. Without a specific part of the extracted surplus-labour being distributed to them, it would be impossible for them to sustain themselves and for capitalist relations of exploitation to be reproduced (Resnick/ Wolff 1982: 3, as well as Resnick/ Wolff 1987, 118-20). Any pejorative epithets that might be attached to them should therefore be rejected and their importance for reproduction of the capitalist system emphasised (Resnick/ Wolff 1982, 10).

12) In the broad sense of the term: production of material and immaterial products.

13) As J. Bidet observes:

“The capitalist who sells services is not a seller of labour power, a form of commercial capital. The capital in his possession pervades all stages of the cycle Money- Commodity...Productive Capital...Commodity'-Money'. Money is used in the market for Commodities, i.e. labour power and other means of production and is transformed into productive capital at the moment when the labour power consumes the means of production by producing Commodity', the service that the client pays for with Money'. What is distinctive about this cycle is that the commodity (service) is consumed at the same moment that the process of production is realized. This means that the capital never appears in the form of Capital”

(Bidet 1975-76, 7).

14) As Baudelot-Establet-Malemort put it: “the need for concentration and circulation of capital wrought similar transformations to working conditions of office workers and insurance clerks: regimentation of labour, mechanisation, segmentation of responsibilities and of control of pace and organisation of labour.” (Baudelot/ Establet/ Malemort 1973, 132).

15) For some very interesting research and analyseis on this issue see 1) ΧΧΧ. 1970. Division du travail et technique du pouvoir. Les Temps Modernes, nο. 285: 1559-1586. 2) Aronowitz, S. 1973. False promises. New York: McGRAW-Hill . 3) Crompton R. and G. Jones. 1984. White-Collar Proletariat, London: Macmillan. 4) Anderson, C.H. 1974. The Political Economy of Social Class. Prentice-Hall. 5) Hacker, A. 1970. The end of the American Era. Atheneum.

16) For further elaboration of these issues, see: Ploeg Van der, J.D. 1986. The Agricultural Labour Process and Commoditisation. In The Commoditisation Debate: Labour Process, Strategy and Social Network, N. Long et al. (eds), Agricultural University of Weganingen 1986, likewise Goodman, D. 1991. Some Recent Tendencies in the Industrial Reorganisation of the Agrifod System. In Towards a New Political Economy of Agriculture Friedland W.F. et al (eds), Boudler: Westview Press as cited by Κασίμης και Παπαδόπουλος 1996, 259-61.

17) It is characteristic that gross added value in transport services increased from 91.7 mil. ecu in 1980 to 211.7 mil. ecu in 1992. At the same time the number of working people in this sector increased from 4.7 million in 1985 to 6 million in 1992. See European Commission 1995. The percentage of energy for transportation as a proportion of total energy consumption between 1990 and 1995 covers the following ranges: in France from 22.8% to 28.5%, in Italy from 24% to 30.9%, in Germany from 18.4% to 26.3%, in Great Britain from 24.8% to 30.5% and in the USA from 31.7% to 38.1% (United Nations 1997).

18) The issue of intensification of the rate of concentration and centralisation of capital is far too large a subject for this article. Very briefly we mention that share of global GNP accounted for by the 200 biggest companies increases from 17% (1965) to 24% (1982) and 30% (1995) Source: Monde Diplomatique, April 1997. In absolute terms the turnover of the 200 biggest companies increases from 2,500 billion ecu (1987) to 3,500 billion ecu (1993). As far as the structure of production in the European Union is concerned, we observe that very small companies account for 93% of the total and make up 23.4% of the turnover. Small companies account for 6% of the total and make up 25.8% of the turnover. Medium-sized companies account for 1% of the total and make up 20.1% of the turnover. Finally big companies account for less 1% of the total and make up 30.6% of the turnover.

19) Of course this strategy was also continued after World War II. In the USA, for example, the biggest trade unions achieved two important goals: an agreement on unemployment/ (the Employment Act) and the direct linkage of wage increases to increases in productivity. Undoubtedly these developments contributed to the maintenance of the purchasing power of working people at high levels. However, the trade unions’ exclusive preoccupation with participating in the annual negotiations on wage rates and working conditions left modes of work organisation out of account and beyond crticism. This resulted in a displacement of the field of trade union intervention from the realm of production to the offices of trade union officials and the bureaucratic mechanisms of the State. In relation to this question see : 1) Bebouzy, M. 1984. Travail et Travailleurs aux Etats- Unis. Paris: La Découverte. 2) Duc le, J.M. 1982. Les Etats industriels et la crise, Paris: Le Sycomore, 3)Ιωακείμογλου, Η. 1985. Για μια αντικαπιταλιστική έξοδο από την κρίση. Μέρος III. Θέσεις τ. 13: 67-103.

20) The inability to modify the strategy so as to locate the specific foci of conflict as well as the fact of failure in answering the strategic questions (eg. What is the role of the state? Is there such a thing as neutral development of the forces of production? How important is intervention in the mode of organising relations of production? etc.) contribute to the emergence of forms of politico-ideological withdrawal and movement away from the elaboration of a proletarian ideology and practice.

21) Of course the changes in the politics of the leftist parties are also related to the specific material alliances forged by capital with the popular classes. Free and universal public education, the possibility of achieving upward social mobility, the creation of the Welfare State, the broadening of consumption, were elements of a compromise between capital and labour. But this compromise was one-sided and inscribed within the framework of reproducing existing relations of production. For the incorporating functions of the state see Andréanni/ Féray 1993, 261-2.

22) For example there are many more unemployed people among unskilled workers than among skilled workers (Castel 1999, 21).

23) As R. Castel observes: “The opposite side of desocialization of labour is in reality the re-individualisation which transfers to the working person himself basic responsibility for finding his way professionally.” (Castel 1999, 24).

Bibliography

Althusser, L. 1973. Positions, Paris: Editions Sociales,.

Anderson, P. 1976. The antinomies of A. Gramsci. New Left Review no. 100 (November- December): 5- 78.

Andréanni T. and M. Féray. 1993. Discours sur l`égalité parmi les hommes, Paris: L΄Harmattan,.

Balibar, E. 1985. Classes. In Dictionnaire Critique du Marxisme, ed. Labica G. and G. Bensussan, 170- 179. Paris: PUF.

Baudelot, C., R. Establet , and J. Malemort J. 1973. La petite bourgeoisie en France, Paris : Maspero.

Bensaid, D. 1995. Marx l΄intempestif, Paris: Fayard.

Berthoud, A. 1974. Travail productif et productivité du travail chez Marx, Paris: Maspero.

Bidet, J. 1975-76. Travail Productif et Classes Sociales, Paris: Centre d’ Etudes et de Recherches marxistes.

Bihr, A. 1989. Entre bourgeoisie et Proletariat, Paris: L' Harmattan.

Braverman, Η. 1974. Labour and Monopoly Capitalism, New York: Monthly Review Press.

Carchedi, G. 1977. On the Economic Identification of Social Classes, London: Routledge Direct Editions.

Castel, R. 1999. Pourquoi la classe ouvrière a-t-elle perdu la partie? Actuel Marx no 26: 15- 24.

Castells, M. 1997. The Rise of the Network Society, Cambridge: Blackwell.

Clark, T. N. and S. M. Lipset. 1991. Are Social Classes Dying? International Sociology vol. 6 (4): 397- 410.

Clark, T. N., S.M. Lipset, and M. Rempel M., 1993. The Declining Political Significance of Social Class. International Sociology vol. 8(3): 293- 316.

Colliot-Thélène, C. 1975a. Contribution à une analyse des classes sociales. Us et abus de la notion de travail productif. Critiques de l' Economie Politique no. 19 : 37- 42.

----------------------. 1975b. Contribution à une analyse des classes sociales. Critiques de l' Economie Politique no. 21: 93-126.

Cottrel, A. 1984. Social Classes in Marxist Theory. London: Routledge & Keagan Paul.

Croix de ste, G. E. M. 1984. Class in Marx's Conception of History, Ancient and Modern. New Left Review no 146 (July- August): 94- 111.

Cutler, A., B. Hindess, P. Hirst and A. Hussain. 1977. Marx's Capital and Capitalism Today, Vol. 1. London: Routledge & Keagan Paul Ltd.

Dahl, R. 1976. Modern Political Analysis. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

European Commity. 1995. Panorama of EU Industry 95/96, Brussels-Luxembourg.

Φεραγιόλι, Λ. 1985. Αυταρχική Δημοκρατία και κριτική της Πολιτικής, Αθήνα: Στοχαστής, Fukuyiama, F. 1992. The end of History and the Last Man, London: Penguin.

Gorz, Α., 1974. Caractéres de classe de la science et des travailleurs scientifiques. Les Temps Modernes no. 330: 1159-1177

Harnacker, M. 1974. Les concepts élémentaires du materialisme historique, Bruxelles: Contradictions.

Harvey, D. 1984. The Limits to Capital, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Ιωακείμογλου, Η. 1990. Το τέλος της Αριστεράς και η ανάδυση των αντικαπιταλιστικών κινημάτων. Θέσεις τ. 30: 25-42.

Johnson, Τ. 1977. What is to be known? Economy and Society vol. 6 (2): 194- 233.

Κασίμης, Θ. και Παπαδόπουλος Α. 1996. Μαρξ και καπιταλιστική ανάπτυξη στη γεωργία: Αγροτική Οικογενειακή Εκμετάλλευση και Διαδικασία της εργασίας. In Αναδρομή στο Μαρξ επιμ. Ν. Θεοτοκάς, Δ. Μυλωνάκης, Γ. Σταθάκης: 247- 267. Αθήνα: Δελφίνι.

Labica, G. 1985. Circulation (procès de). In Dictionnaire critique du marxisme ed. G. Labica and G. Bensunssan, 167- 170. Paris: PUF.

Lenin, V.I.1977. A Great Beginning, Peking: Foreign Languages Press.

Macpherson, C.B. 1985. Principes et limites de la démocratie libérale. Paris: La Découverte.

Marx, K. 1885. Capital. Volume 2, http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1885-c2/ch04.htm.

-----------. 1973. Grundrisse. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

-----------. 1974. Théories sur la plus-value, Tome 1, Paris: Editions Sociales.

-----------. 1975. Théories sur la plus-value, Tome 2. Paris: Editions Sociales.

-----------. 1978. Capital, Volume 3, London: New Left Review.

Μαυρουδέας, Σ. 1993. Ο Ι. Ι. Rubin και η συνεισφορά του στη Μαρξιστική Πολιτική Οικονομία. Θέσεις τ. 44: 69-83.

Miliband, R.. 1973. L' Etat dans la société capitaliste, Paris: Maspero,.

Nagels, J. 1974. Travail collectif et travail productif, Bruxelles: Εditions de l' Université de Bruxelles.

Nations Unis. 1997. Bulletin Annuel de Statistiques des Transports. NY- Genève.

Pakulski, J. 1993. The dying of Class or of Marxist Class Theory?, International Sociology vol. 8 (3): 279- 292.

Palloix, C. 1977. L' Economie mondiale capitaliste et les firmes multinationales. Paris: Maspero.

Poulantzas, N. 1978. L' Etat. le Pouvoir, le Socialisme. Paris: PUF.

----------------. 1979. Classes in Contemporary Capitalism, London: Verso.

Resnick, S. and R. D. Wolff. 1982. Classes in Marxian Theory. The Review of Radical Political Economics, vol. 13 (4): 1- 18.

-----------.1986. Power, Property and Class. Socialist Review, vol 16 (2): 97- 124.

-----------.1987. Knowledge and Class. A Marxian Critique of Political Economy. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Saunders, R. 1995. Social Theory and the Urban Question. London: Routledge.

Sakellaropoulos, S. 1999. Pouvoir Politique et Forces Sociales en Grèce d`aujourd`hui (1974-1988). Lille: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion.

Τσεκούρας, Θ. 1987. Ποιος θυμάται ακόμα την επανάσταση; Θέσεις τ. 17: 19-46

Weber H. and O. Duhamel . 1979. Changer le PC?, Paris.

Wright, E.O. 1980. Varieties of Marxist Conceptions of Class Structure, Politics and Society vol. 9 (3): 323- 370.

Biographical Statement

Spyros Sakellaropoulos

Visiting Lecturer of Sociology at the University of Crete at Rethynmno. His most recent work is Greece after the dictatorship 1974- 1988 (Livanis Editions, 2001- in Greek). At the moment he is working on a book about globalization, the new imperialism and the strategy of the capital.

Spyros Sakellaropoulos

e-mail: sgsakell@otenet.gr sgsakell@phl.uoc.gr

adresse: L. Alexandras 60, 15125, Athens Greece

tel. ++ 0106810136, ++ 0938331830