Peter Gowan’s Theorization of the Forms and Contradictions of US Supremacy: A Critical Assessment

Peter Gowan’s Theorization of the Forms and Contradictions of US Supremacy: a Critical Assessment

Spyros Sakellaropoulos

Department of Social Policy, Panteion University Athens

sgsakell@vivodinet.gr

Panagiotis Sotiris

Department of Sociology, University of the Aegean, Mytilene

psotiris@otenet.gr

Introduction

During the past years Peter Gowan emerged as one of the most important writers on international relations from a Marxist perspective and provided one of the most interesting and coherent descriptions of US efforts to establish and maintain a predominant position in the international system. Although he did not often use the notion of imperialism, we believe that he can be considered one of the main Marxist theorists of ‘new Imperialism’. His death in June 2009 put an early end to a life of political and theoretical commitment. In the following paper we attempt a presentation and critique of Gowan’s main positions.

1. Gowan on the US strive for world dominance

1.1 National interests and political strategies

One the main features of Gowan’s interventions was his refusal of traditional theoretical demarcations and his insistence on combining international relations theory with international political economy. Contrary to mainstream globalization theories which tend to underestimate the scale and importance of interstate rivalries and hierarchies Gowan grounded his analysis on a theorization of the national interest as the national capitalist interest (Gowan 1999: 63). This helped him define the national interest of the US as the dominant capitalist state: the US government will ensure the access of American capitals to regions of market growth, dynamic pools of labour and product markets, the creation of suitable institutions and the prevention of exclusion from major markets (Gowan 1999: 69).

But Gowan also provided very interesting analyses of the political strategies articulated by the American state in order to defend the interests of US capitalism and secure American supremacy. According to Gowan the roots of the strategy for American global dominance in the international capitalist world can be found in the manner the American state and political system is designed to serve the interests of the American business class in ways that cannot be found in other social formations (Gowan 2004a: 4). Gowan does not support the conventional wisdom that the American state leadership during the Cold War was the result of the confrontation and polarization with the Soviet bloc and communism. On the contrary he insisted that the US strategy was defined in the end of the 1940s as an aggressive strategy not only to contain the Soviet threat but to create conditions for a positive American World Order:

It mounted a huge military challenge to the Soviet bloc, impelling the USSR to adopt the only deterrent option available to it at the time: the threat to overrun Western Europe. This in turn, bound the West European allies, utterly dependent on US strategic nuclear forces, to the United States’ (Gowan 2004a: 6)

This effort was not centred only on Western Europe. It also led to a system of regional alliances that gave the US the ability to directly influence and command the political strategies and security policies of the other main capitalist centres. This in turn led to the formation of an American protectorate system that covered the capitalist core, with a distinctive ‘hub-and-spokes’ character that dictated that each protectorate’s primary military-political relationship had to be with the United States (Gowan 2002: 2). This American strategy was not only a political-military one, but it also had a social substance (Gowan 2004a: 8): the defence of intensive ‘fordist’ capital accumulation against social unrest and labour militancy, the unfettered access of American business interests (and the American governmental and non-governmental organizations designed to promote American business interests) to all the main centres of accumulation, and the preservation of American control over the international monetary systems and American dominance in ‘high tech’ fields (Gowan 2002: 6).

1.2 The ‘Dollar-Wall Street Regime’

American strategy came under severe pressure during the 1970s because of the international capitalist crisis and the economic challenges posed against the US by the other main capitalist centres. The American answer to this was two-fold according to Gowan. On the one hand we had the Reagan Administration’s effort for an offensive strategy against labour and social rights and the implementation of an aggressive strategy for capitalist accumulation.

Capitalist classes were offered the prospect of enriching themselves domestically through this turn, as rentiers cashing in on the privatization or pillage of state assets and as employers cracking down on trade unions etc. And the restrictions on the international movement of capitalist property –the system of capital controls– would also be scrapped, giving capital the power to exit from national jurisdictions, thus strengthening further their domestic power over labour’ (Gowan 2002: 7)

On the other hand we had what Gowan described as the ‘Dollar-Wall Street Regime’. This is the policy adopted by successive American administrations from the 1970s on, in order to retain the hegemonic position of American capital in the International monetary system. According to Gowan the ‘financial repression’, which characterized the Bretton Woods Regime, was abandoned by the Nixon Administration who wanted to ‘break out of a set of institutionalized arrangements which limited US dominance in international monetary politics in order to establish a new regime which would give it monocratic power over international monetary affairs’ (Gowan 1999: 19). This was not just an economic policy choice but also an effort to increase the political power of the American state since the dollar seigniorage offered the American government a potential political instrument. This turn was intensified during the Reagan administration, when money capital was given precedence as far as policy was concerned, and the US initiated a drive towards the elimination of capital controls, something that facilitated internationalization of American finance capital. According to Gowan the Clinton administration, in its effort to secure American post-cold war predominance, gave particular emphasis to economic statecraft. Although articulated in terms of ‘globalization’, it was in fact a drive to open borders to US goods, capital and services. Since the US could not keep its predominant position through direct coercion and subordination, it had to ‘achieve its goal within them states through the existing dominant social class within them’ (Gowan 1999: 81). Globalization is described as an aggressive political effort of the US to radically transform the economies of the rest of the world in directions converging with the interests and needs of US capitalism (Gowan 2000: 24). But there were also contradictions arising, especially because of the tremendous expansion of financial capital activities that could result to new vulnerabilities for the US economy: ‘this expanded political freedom to manipulate the world economy for US economic advantage has ended by deeply distorting the US economy itself, making it far more vulnerable than ever before to forces it cannot fully control’ (Gowan 1999: 23).

This strategy reflected the changing nature of capitalist accumulation within the US economy. According to Gowan we can talk about a bifurcation of American Capitalism (Gowan 2004a) because of the growing importance of American transnational capitalists in relation to American domestic market forces. Gowan rejected the globalization theorists’ claim that transnational capitalists break with their ‘territorial state’. On the contrary, he insisted that this fraction of the American bourgeoisie has more or less exercised control on the American state:

[T]he relation between American transnational capitalists and the American state remains that of robust, mutual loyalty. One key empirical test of this would surely be to see whether this (dominant) wing of the American capitalist class has worked to build new, supranational institutions for enforcing their property rights internationally, over and above the American state. There is not the slightest evidence of this. Another would be to see whether the American state has worked to penalize the transnational expansion of American capitals. Again, no evidence of this exists (Gowan 2004a: 15).

The rise of the transnational sector of the American capitalist class also led to a rising importance of the financial sector. At the same time the domestic American economy went through a phase of de-industrialization and the mass restructuring efforts of the 1970s and the 1980s did not result in a revitalization of American industry. This financialization of the American economy led to the emergence of a rentier-like capitalist class that provided the main social basis for the ‘Dollar-Wall Street Regime’. This American strategy offered the other capitalist states policy suggestions such as massive privatizations and finance liberalization. It also offered, Gowan insisted, an unstable monetary and financial regime and questions as to which these policies are ‘actually capable of stabilizing new institutionalized arrangements (Gowan 2004a: 22). That can explain the lack of full support for American ‘market state’ strategy from the European states, with the notable exception of Britain.

1.3 Post-Cold War challenges

But the American strategy for world primacy (and the implementation of the Dollar-Wall Street Regime) was never a purely economic strategy. Mainly it had to do with political power relations. The end of the Cold War posed for the US the problem of recreating an international structure capable of renewing their primacy. In order to achieve this goal it had to undermine the two rival projects for Europe in the post-cold war Europe: (a) The ‘One Europe’ project (Gowan 2000: 31) which had the support of West Germany, France and Gorbachev but lacked the support of big capital (because of its reference to a social-democratic developmental strategy) and of course the US. (b) The ‘European Union’ as a fully-fledged political entity expanding into East Central Europe, that would replace American hegemony with a ‘two pillar alliance (Gowan 2000: 37). The US managed to avoid implementation of such policies with an aggressive effort for NATO ascendancy in the whole of Europe under American leadership. The war in former Yugoslavia offered the possibility for such a reassertion of US primacy, with the US successfully imposing their policy of Bosnia recognition and making sure that there would be an American-led NATO military full-scale war against Serbia over the Kosovo problem, with the US ‘successfully manoeuvring the West European States into the NATO war against Yugoslavia’ (Gowan 2002: 17).

However successful the American strategy was at undermining other projects, Gowan insisted that there were important contradictions and problems that had to be dealt with (Gowan 2004a: 26-29): (a) the problem of the far wider scale for this truly global primacy, (b) the question of how to keep the other capitalist core-states strategically dependent upon the US, (c) the erosion of the ‘hub-and-spokes’ structure of US relations with other countries, (d) the question of legitimacy both internationally and domestically, (e) the exact nature of the relation with Europe. The Bush administration’s strategy tried to address these questions in order to make ‘the security of all the main Eurasian powers more dependent upon the United States’ (Gowan 2004a: 29). This strategy was legitimized through the assumption that the American State and American Capitalism will lead the world in a great mission to bring democracy, prosperity and modernity to the rest of the world. But this strategy also needed the reality of the terrorist and ‘islamist’ threat and the US has taken all the necessary steps through their support of Israel and the occupation of Iraq. According to Gowan the American strategy has not been the only one offered. He believed that the US is also confronted with a different set of principles put forward by the West European States, which point towards a new form of Atlantic/OECD Hegemony using the structural forms of law (Gowan 2002: 23). He describes this project as ‘ultra-imperialist’ in contrast to the ‘superimperialist’ American project (Gowan 2002: 25). It is also important that he contrasts the reality of the American attempt for supremacy in the international system to what he designates as ‘liberal cosmopolitanism’ (Gowan 2001). Gowan insisted that it is not possible to talk about a collegial way to handle world affairs and bring international harmony through supranational institutions.

1.4. The question of empire

At a more theoretical level Gowan addressed the question of a capitalist world-empire in a very interesting dialogue with World Systems Theory (Gowan 2004). First, Gowan rejected the US hegemonic decline thesis advanced by Arrighi and then rejects World Systems Theory’s insistence on the theoretical impossibility of a capitalist world empire (Gowan 2004: 484). According to Gowan, arguments against the possibility of such an empire rest upon two premises: Sovereign states and world empires are mutually exclusive and there is a structural tension between capitalists and an empire state (Gowan 2004: 487). Contrary to these arguments he insists that an imperial relation is not necessarily a juridical form of command and compliance; ‘a world empire can be an inter-state system and international political economy shaped and structured in ways that generate empire-state re-enforcing agendas and outcomes’ (Gowan 2004: 488). He also proposes certain preconditions that would make an empire state appealing to capitalist classes in the other states:

‘a. The empire-state presents itself as the champion of the most unrestricted rights of capital over labour within all the states of the core […]

b. […] the empire-state offers itself as an instrument for expanding the reach of all core capitals into the semi-periphery and periphery […]

c. […] the empire state offers a new model of capitalist organisation which brings very large additional pecuniary rewards to leading social groups within other core states […]

d. […] the empire-state offers a mechanism for managing the world economy and world politics which is sufficiently cognisant of trans-core business interests’ (Gowan 2004: 490).

According to Gowan (2004: 492-498) the American business and political elites have been pursuing a world empire project for the past twenty years and have tried to present the US as the leader of global capitalist interests by leading the attack on labour rights, securing the expansion of capital in the Semi-Periphery and Periphery, increasing the American bargaining power against non-American Businesses, resisting pressures for a more collegial institutionalized form of global governance, and using the boom in the American economy during the 1990s to gain broad support from the capitalist classes of the rest of the core. Politically they have prevented other core states from gaining regional geo-strategic autonomy, they have tried to prevent European Political Unity, although this project is still a possibility, they have prevented Pacific regional Political-Economy integration, they have tried to maintain international monetary and financial leverage, although both Western Europe (through the Euro) and Japan have taken steps to protect themselves from American economic statecraft, they have tried to gain strategic control of the international division of labour, although both Japan and Western Europe resist this tendency. Apart from the contradictions already mentioned, the US world empire suffers from the contradictions in the American economy, the huge growth in private indebtedness, the absence of sustained growth motors, and the lack of appeal of the American business system of shareholder value for many members of the business classes in the other core capitalist states. And since the progress of the American project for an American capitalist world empire has been based upon the weakness and political disorientation of labour after the collapse of the Soviet Union, a possible revival of the strength of labour and anti-capitalist movements can ‘be used by core powers to advance a programme of more collegial and institutionalised world government against the unipolar, US-governance instruments which have been unchallenged in the 1990s’ (Gowan 2004: 499).

1.5. Contradictions and conflict in the international system

In a more recent paper (Gowan 2005) Gowan took up the subject of structural sources of conflict between the main centres in the capitalist core and he tries to define a possible third position opposed to both those theories that insist on a lack of structural conflict within the capitalist core (with Panitch and Gindin as the main proponents) and those theories that try to describe an intense struggle for hegemony, as it is the case with Giovanni Arrighi who sees an acute crisis of American hegemony. Gowan made a distinction between structural sources of conflict and inter-state rivalries and insisted that structural sources of conflict do not necessarily lead to politicized open inter-state rivalries. He laid a theoretical framework to explain why it is important for capitalists to be able to expand their economic activities beyond the borders of their states, something that makes possible transnational economic linkages between social groups in different states. But this process is not a purely economic process, it is also a political process, because the internal regime of each state can enhance or weaken the possibilities for expansion.

‘Therefore the nature of the internal socio-economic, legal and political regimes within states lies at the heart of capitalist international economics. The profitability of international economic operations in a capitalist world can always by enhanced by or weakened by a vast range of different changes in the internal regime of any state. Therefore, capitalist classes have powerful economic reasons for seeking to maximize the influence of their state over the state of the internal regimes of other states. Thus capitalist economic expansion abroad is always deeply connected to efforts to reshape the internal social and political regimes of other states and is always pre-occupied with ensuring that these internal regimes continue to protect and facilitate the property expansion of the source capitalism’s capital. These are always more or less political questions, questions of power.’ (Gowan 2005: 3)

It was on this basis that certain states have tried in recent history to establish their domination over other states’ internal regimes, in ways suitable for their capitals, at the same time presenting it as leadership of a community with a shared identity that has to struggle against a common enemy. In this sense the economic and the political aspects of the internationalization of capital are interlinked.

Based on this general framework Gowan proceeded to locate two structural causes of conflict in the capitalist core. The first one concerns the dynamics of industrial competition. He stresses the importance of increased returns on scale and the ways these lead to conflicts between the states that can generate great scale economies and those that try to respond to this. So ‘it is simply false to claim that individual MNEs have lost their national identities. On the contrary they depend very heavily on external supports within their home states’. (Gowan 2005: 10). In this way he described how West Germany and Japan had to find ways to cope with the scale of American industry in order to compete with the American leadership in the international division of labour. West Germany viewed the EU as a regional base for German industry. Japan concentrated resources on high tech sectors. Contrary to globalization theories ‘property expansion of the main centres of capitalism is overwhelmingly regionalized’ (Gowan 2005: 12) and the same goes with cheap labour hinterlands (Gowan 2005: 15). Gowan thought that we can talk about forms of a new mercantilism in the capitalist core centres and he cites dumping policy, anti-trust legislation, Free Trade Agreements and what he described as ‘High Tech Mercantilism’ (Gowan 2005: 19) e.g. in sectors as semi-conductors and civilian aircraft production. He also thought that because of industrial rivalry in high tech sectors the US is no longer industrially hegemonic (Gowan 2005: 23). As a result there has been an effort by the US and Britain to change the institutional forms of capitalism in on order to increase the power of money and rentier capitalists and to expand this kind of internal institutional and corporate management regime in all capitalist core centres and this can explain the American financial globalization drive. The second cause of structural conflict lies with the contradictions within international monetary relations after the collapse of the Bretton Woods System and the way the US has used the movement of the value of dollar in order to maintain dollar dominance.

But there has also been a structural source of political conflict within the capitalist core. The US achieved primacy because they could make all other capitalist states dependent on them for their security against the Soviet Bloc. The collapse of the Soviet Union reduced the security dependence of West Europeans and destroyed the ‘free world - Communist totalitarianism cleavage that generated the political values that defined the US’s political community’ (Gowan 2005: 30). As a result successive American administrations have tried to find ways to create again conditions of mutual dependence on the part of all the great powers on the US, and this can explain the Bush administration’s emphasis on ‘international terrorism’, rogue states and weapons of mass destruction. It is on this basis that he defines the structural causes for political conflicts: On the one hand the US is trying to create conditions of what he called ‘American Global Government’ (Gowan 2005: 31), legitimized through a reformed UN and hegemonic political alliances. On the other hand, ‘France and Germany [are] still trying to build a semi-autonomous political community of shared political values under their leadership with a Europeanist base but with a universalist-cosmopolitan mission statement. […] The leadership of the US capitalist class is seeking to resist this and restore US primacy’ (Gowan 2005: 31).

Similar arguments can also be found in Gowan’s reply (Gowan 2005a) to articles presented in Critical Asian Studies (Palat 2005; Berger and Weber 2005; Nordhaug 2005; Prashad 2005; Vicziany 2005) that criticized aspects of his positions. The first argument concerns the attention paid to the role of East Asian economies and their financial systems. Gowan admited having underestimated their importance, but insists that they do not ‘mark a structural power shift in the international economy’ (Gowan 2005a: 416). The second argument is about criticisms of Eurocentrism and Atlanticism in his theoretical perspective. Gowan’s counterargument is that the stake at a global level is for the US to reassure its leadership in a world community of capitalisms, and this explains why he makes the US relation to Europe and Japan an analytical priority.

‘The problem, then, for the United States, is not to be the most powerful state in the world in the context of some aggregate of rising and declining powers. The problem is to build a world community of capitalisms that the United States leads. This is a problem of reconfiguring the relations between states and capitalisms in a way that enables the United States to govern the whole system in a sustained, long-term fashion that will enable capitalism to flourish’ (Gowan 2005a: 418)

But the main focus of Gowan’s reply dealt with his criticism of Globalization theories. He insisted that there are structural contradictions between transnational integration and political fragmentation and there has not been any form of transcendence of the inter-state system. His argument was threefold: First, the ‘world remains structurally fragmented economically into a mass of politicized monetary zones’ (Gowan 2005a: 422), something that means that the importance of the state is far from over. Secondly, the importance of economies of scale in the high technology sectors makes necessary for leading capitalist enterprises to have a strong support from states that cannot be described as ‘exhausted’. Finally, he insisted that the trend towards the unfettered movement of money capitals should not be analyzed as the advent of globalization, but — taking into consideration that at the same time Germany and Japan developed forms of corporate governance that enabled them to compete with US enterprises — more as a complex form of ‘industrial rivalry by financial-operator means’ (Gowan 2005a: 429).

1.6 The current economic crisis and the ‘New Wall Street System’

Peter Gowan’s last major contribution was a theoretical confrontation with the current economic crisis (Gowan 2009). Gowan’s main argument is that the current crisis is not the result of a bubble in the real economy, but of the structural transformation of the American financial system and the emergence of a ‘New Wall Street System’ (Gowan 2009: 6). He attributed this emergence to a set of changes in the American financial sector, such as the turn of investment banks’ trading activity towards speculative proprietary trading and forms of speculative arbitrage, which created a whole financial strategy of ‘blowing bubbles, bursting them and managing the fall-out by blowing some more’ (Gowan 2009: 10). This strategy required greater than ever scale of financial operations and led Wall Street Banks to push their borrowing to the leverage limit. This, in turn, led to the expansion of a shadow-banking sector in the form ‘new entirely unregulated banks, above all the hedge funds’ (Gowan 2009: 13), which led to the rising importance of new forms of credit derivatives. This financial architecture was not based solely in Wall Street. According to Gowan London became more and more important as an even more unregulated node of unregulated financial activity. The bubble that sparked the current crisis was generated not ‘in the housing market, but in the financial system itself’ (Gowan 2009: 18). The refusal of the suppliers of funds to continue to support the speculative accumulation of debt brought forward the contradictions at the core of the New Wall Street System. That’s why Gowan is very critical of the tendency, especially among social-democratic circles, to attribute the crisis to free-market or ‘laissez-faire’ ideologies. Gowan thinks that although these ideologies did indeed have a legitimisation role, neither Alan Greenspan of or the big bank chides believed in the transparency or efficiency of markets. On the contrary they accepted the risk of bubbles and blow-outs and were aware of the possibility of widespread negative turns in markets, but insisted on the possibility of deregulation as means to maximize earnings between blow-outs and of the state being able to cope with the consequences (Gowan 2009: 21).

Gowan thought that this crisis makes urgent a debate on what kind of financial system is required. He insisted that ‘public ownership of the credit and banking system is rational and, indeed, necessary along with democratic control’ (Gowan 2009: 22) as opposed to the self-expansion of money capital that is at the core of a private capitalist credit system. He also insists that in order to deal with the inherent instability of the credit system, these systems have to be ‘underwritten and controlled by public authorities’ (Gowan 2009: 23) and here the importance of the nation-states persists. On the contrary what has been termed ‘economic globalization’ aims at depriving states of this capacity.

But the main obstacle in such a direction has to do with the ways the New Wall Street System achieved hegemony within the US economy. Gowan thinks that the main reasons were the failure of the attempt to revitalize American industry as opposed to the rising profitability of the financial sector and the ability of the financial sector to supply the credit to stimulate consumer demand and sustain the 1995-2008 American boom and consequently the leading position of the US in the world economy, despite the fact that it was based on debt and projections of future growth and not gains in real value-production.

Gowan’s conclusion is that this crisis will have important ideological and political implications. It will reinforce the ‘creditor relations between the Atlantic World and its traditional South in Latin America’ (Gowan 2009: 27). It will lead to more open discussion of the ‘public-utility model’ for the financial sector. It will raise the importance of East Asian economies and especially China in global macroeconomic trends. For Gowan although the current concentration of China on domestic growth offer prevents the US from facing a direct threat, in the long run the US will face the contradictions of its leading capitalist class:

[S]uch is the social and political strength of Wall Street and the weakness of the social forces that might push for an industrial revival there, that it would seem, most likely that the American capitalist class will squander its chance. If so, it will enjoy another round of debt-fed GDP growth funded by China and others while the US becomes ever less central to the world economy, ever less able to shape its rules and increasingly caught in long-term debt subordination to the East Asian matrix. (Gowan 2009: 29).

2. Gowan’s contribution to the theory of imperialism: a critical assessment.

2.1 The merits of Gowan’s work

There is no doubt that the work of Peter Gowan has been one of the most important Marxist contributions to the theorization of international relations and conflicts. It is very important that right from the start he distanced himself from theories of a borderless transnational capitalism and he denied the theoretical possibility of a transnational capitalist class without ties to any particular state. This helped him to formulate elements of a theory of the ways national states use to promote the class interests of their capitalists outside their territorial borders. This is very important, because only on such a theoretical basis it is possible to articulate a theory of modern imperialism. His rejection of globalization theory’s simplifications, at a time when they were considered some sort of orthodoxy, helped him to formulate a notion of American drive for global supremacy long before 9/11 and the ‘rediscovery’ of American unilateralist tendencies. He also provided a rather convincing account of the class forces and social interests behind American policy in the form of the ‘Dollar-Wall Street Regime’ and he proved the fallacy of any attempt to theorize a possible American decline during the last decades. At the same time his assessment of the current economic crisis offers an insightful analysis of the structural contradictions at the heart of the American articulation of political and financial strategies. His description of American policy in the 1990s as a bid for global domination is very helpful because it provides a convincing answer to all those who have tried to oppose the policies of the Bush administration to the supposedly more humane and more globalist policies of the Clinton administration. Particularly important was his analysis of the American policy towards Yugoslavia as an effort to reinstate the American primacy and to undermine potential challenges to it, thus refuting the ideological myth of western ‘humanitarian’ intervention in the Balkans. We also think that the way he defined the different strategies in the International System, in the form of an opposition between American imperial attitude and the European will for a more collegial management of world affairs provides useful insight into the contradiction developing between capitalist core countries and the same goes for the way his based this on an analysis of the different class interests and accumulation strategies that different international policies express. We also find his insistence on structural causes of conflict within the capitalist core very important, because we think it provides the basis for rejection of current variations of the old ‘ultra-imperialism’ theory. It is exactly this emphasis on the centrality of conflict that grounds his correct rejection of the possibility of more ‘collegial’ ways to manage international affairs through forms of supranational governance.

2.2. Points of criticism

But we would also like to stress some points of disagreement with Gowan’s approach.

2.2.1 The problem of a theory of imperialism

On a more theoretical level the main criticism that can be directed against Gowan’s perspective is the lack of a comprehensive theorization of the phenomena that international relations theory has to deal with. In our opinion, one of the main problems facing any possible theorization of imperialism is how to avoid a relapse into traditional geopolitical realism. The affirmation of the importance of the political in inter-state relations, and the acceptance of a general notion of 'national interest', can easily lead to a traditional description of power politics and of states as autonomous subjects. What is needed is not an abandonment of the importance of states, of the relative autonomy of the political and of the articulation of economics and political power at the international level, but a problematization of the very notion of political power. Political power should not be viewed as simply ability to command but as the complex expression of an objective class interest as political strategy, form of governance, ideological practice, alliance building, in general as hegemony. One-dimensional theories of imperialism tend to underestimate exactly this interplay (or dialectic) of the economic, the political and the ideological in modern imperialism. Theories that overemphasize the economic tend to neglect the importance of political antagonisms and are too eager to affirm the emergence of a global social formation. Theories that overemphasize the political fail to explain the relation of political strategies to the conjuncture of capitalist accumulation.

In light of the above, we have to stress that however important Gowan’s political and analytical insights are the reader of his work is left with the impression that he has been reading a left-wing or Marxist variant of a more or less mainstream combination of realist-oriented international relations theory and international political economy. Of course this a problem not only of Gowan, but also of other theorists of the ‘new imperialism’ who tend to combine an analysis of the international economic conjuncture with a more or less realist notion of national interest and balance-of-force politics. As Gonzalo Pozo-Martin has recently shown (Pozo-Martin 2006; 2007) the problem lies exactly in the weak theorization of the capitalist state and the articulation of the economic and the political that provides the social, material foundation of modern imperialism.

The classical Marxist theories of Imperialism, especially Lenin’s[1] had at least one major theoretical advantage. It was an attempt to provide a comprehensive and thorough theorization of the international system both at the macro and micro level, thus combining a theory of the stage of capitalism, of the form of the state and the relations. In doing so they were revolutionizing the theorization of interstate relations, exactly because they were trying to transcend the internal / external divide, by focusing on the ways the class struggle — in the last instance — conditions both societal tendencies and international conflicts. Describing imperialism not as a symptom of Great Powers confrontation, but as a stage in the history of capitalism as a mode of production, had exactly this major theoretical gain, even if today one has to abandon many of the tenets of traditional imperialism / monopoly capitalism theories. Also of importance, in the same perspective is a rereading of attempts in the 1970s to rethink the notion of imperialism though the lenses of the advances made in state theory, especially those related to Poulantzas’ work (Poulantzas 1973; 1974; 1975; 1978).

What is needed today is a collective theoretical effort to articulate the current frame of productive relations, the tendencies of capital accumulation, the contemporary forms of class divisions and alliances, the forms of state, the specific forms of internationalization of capital and current imperialist practices, into a coherent theoretical apparatus able to produce the theory of the capitalism (and imperialism) of our age.

2.2.3 Questioning the role of financial capital

Our second point of criticism concerns the problem of finance capital and the class strategy it expresses. While we do not disagree on its importance within the American class structure[2] and the role it plays in the whole process of the internationalization of capital, facts that have been noted by many Marxists writers, we think it characterizing it as rentier-like misses the point. Distinguishing between the possibly positive social role of production capital and ‘unproductive’ rentiers has a long history not only among Marxists, but also among bourgeois theorists and commentators. However this normative distinction is based upon a lack of theorization of money-capital. If we consider money as an expression of the value-form, as an abstract embodiment of capital as a social relation then we can think of finance capital not in terms and speculation and short term gains, but a an aggressive expression of capital’s drive towards self-valorisation, that is exploitation of living labour[3]. In this sense the predominance of finance capital in today’s internationalization of capital has been instrumental for the crackdown on labour rights and the whole change in the balance of forces between labour and capital. It is true that American share-holder value forms of management that give priority to short term profits, are different than European emphasis on long term returns on investment, but the fact that we have not seen such an acceleration of a turn towards American style management has more to do with the relative strength of European labour in comparison to the situation in the US, although recent government changes in major European capitalist states has led to accelerated efforts for an ‘Americanization’ of the labour market. And we must also add that not all of Europe is so opposed to American finance capital aggression. Not only Britain, but also the ‘New Europe’ countries have based their accumulation strategies to cheap labour, lack of workers rights (in the case of some Baltic states also lack of civil rights for a great part of their population), flat taxes and full compliance with the exigencies of international capital.

2.2.4 US and EU

We also disagree with aspects of Gowan’s assessment of capital restructuring within the domestic US economy. Although it is true that not all of the expectations created by the 1990s boom were fulfilled, one cannot deny the fact that there were genuine significant productivity gains in the US economy, in the form of organizational and technological innovations, and that the US retained also its productive leadership, especially against the EU.

And it is interesting that the adoption in 2000 by the EU of the so-called ‘Lisbon Strategy’ for obtaining technological and production superiority towards the US was followed by a much deeper European recession. The Lisbon strategy constituted the decision of a special European Council held in Lisbon in 2000 to adopt a new strategy for the EU economy. Their intention was to make EU ‘the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world, capable of sustainable economic growth with better jobs and greater social cohesion’ (cited by Blanke and Lopez-Glaros 2004: 1). This strategy had 8 specific goals: 1) creating an information society for all; 2) developing a European area for innovation, research and development; 3) liberalization; 4) building network industries; 5) creating efficient and integrated financial services; 6) improving the enterprise environment; 7) increasing social inclusion; 8) enhancing sustainable development. The real causes for this policy was the necessity of some form of action against the persistence of high rates of unemployment and low competitiveness in a time when ‘technological and scientific innovation had come to acquire a prominent role in enhancing countries’ long- term growth capacity’ (cited by Blanke and Lopez-Glaros 2004: 2). So, the real goal of all this initiative was for the EU to become the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world.

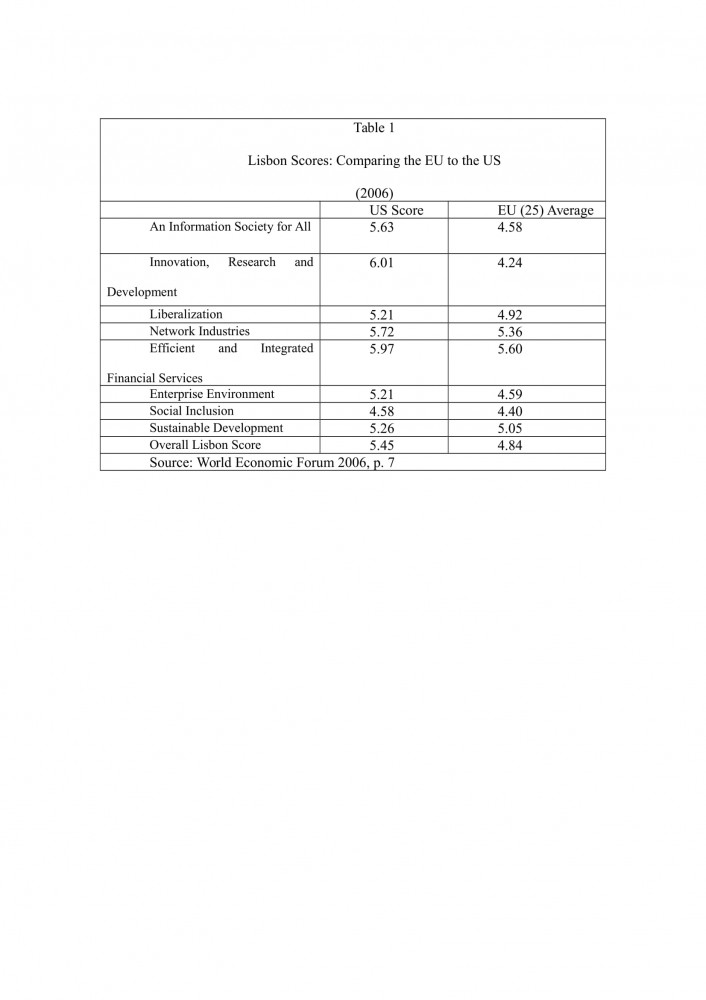

What are the results of this policy? Every year the World Economic Forum presents the Lisbon Review where EU scores are compared to those of the US.

In sum, the EU performs worse than the US in almost all areas. So, these scores show that the gap between the EU and US economy is getting deeper. In contrast to Gowan’s, and many others’ position, the US had a relatively strong economy during the 2000s, at least until the eruption of the sub-prime mortgages crisis. The European leaders adopted the Lisbon strategy because they realized the American economic superiority. Although the average annual rise of American productivity was 0.6% in the years 1986-1990 compared to 1.5% in the EU and 2.6% in Japan, after 10 years the situation has been completely reversed; American productivity has been rising by 1.3% annually, the Japanese by 0.4% and the European by 0.7% (European Economy 2002). The result is, according to the World Economic Forum, that the US had the first place in global competitiveness in 1994 and 1995. The participation of US companies in the list of the 500 bigger companies in the world rose from 151 in 1994 to 185 in 1998 (Bergesen / Sonnet 2001: 1607). In 1997 the German and Japanese economies combined reached only 56% of the American economy, while the Japanese German, British and French economies combined reached 87% of the American economy (Barrow 2005: 17). The participation of the US in the global production of added value rose from 24% in 1987 to 26.9% in 1994 (Dichen 1999: 28). The very next years the production of value added accelerated: Between 1987-85 the annual growth rates in GDP were 1,05% and in private industries 1,03%; in contrast to 1995-1999 when it was 1,69% and 2,01% respectively (Stiroh 2001: 40). The fact that the average annual ICT contribution to difference between volume change in gross and net value-added during the years 1995-2000 was 0,19 for the US, 0,04 for Japan, 0,06 for Italy, 0,07 for the UK, 0,08 for Germany, 0,08 for France, 0,13 for Canada, is also very impressive (Collecchia / Schreyer 2002: 423).

The annual growth in real GDP per capita between 1973 and 1998 was 1.99% for the US, 1.78% for Europe and 1.33% for the world average, while the average rate of growth in GDP from 1983 to 2001 reached 3.4% for the US 2.5% for Japan and 2.7% for the UK (Panitch / Gindin 2003-4: 18, 28-29) Last but not least, the US maintained the first place in the global commerce of services (Dichen 1999: 41).

Nine years after its proclamation the Lisbon strategy does not seem to have reached its goals. The American share of the world gross domestic product was 25.6% in 1992 and rose to 28.8% in 2004. In contrast the share of the European economy (EU-15) declined from 31.9% (1992) to 29.75% (2004). At the same time the American share in world Foreign Direct Investment outflows rose from 12,6% (1990) to 31.4% (2004) in contrast to the European share which declined from 40,3% (1990) to 31.8% (2004) (UNCTAD 2006). Gowan’s argument about the failure of the American supremacy is also contradicted by certain indicators like GDP per capita or labour productivity: the GDP per capita was 39% larger in US than in the EU-15 and labor productivity was 20% higher (2003). It is important to note that the gap in productivity became larger during the last few years because the American productivity rose by 1.3% between 1996- 2002 while the European productivity only by 0.6% (European Economy 2002).

The reasons of the American economic superiority can be attributed to the faster accumulation of Information and Communication Technologies’ (ICT) capital (rapid technological change in the ICT-producing industries and rapid ICT investment in other sectors of the economy[4]) in many industries; that trend led to faster acceleration in labour productivity[5]. The gasp in comparison to the European economy became bigger: ICT investment accounted for the 17% of business investment in Europe (2000); the corresponding figure was almost 30% for the US (Ark / Inklaar / McGuckin 2003). Other indicators show that the percentage point contribution of the ICT to output growth was much higher in the US than the other developed countries during the years 1995-1999: 0.86 for the US, 0.28 for UK, 0.29 for Japan, 0.16 for Italy, 0.21 for Germany, 0.26 for France, 0.47 for Canada (Collecchia / Schreyer 2002: 418).

That is why we insist that we should not think in terms of an American productive decline, but in terms of re-emerging tendencies towards over-accumulation and falling rates of profit in all core countries, as a result of unresolved structural contradictions.

We also think that Gowan tended sometimes to draw a rather sharp distinction between American and European Strategies. There are two problems with this approach: a) there is no clear alternative imperialist strategy elaborated on the European side; b) the European states do not have the same interests, so it is not possible for them to create a common strategy. It is true that especially in France and Germany there have been many attempts to articulate a different vision for the International System and this fact reflects the antagonistic tendencies inherent in capitalist imperialism. Their failure to become hegemonic reflects not only their lack of political and military clout, but also the fact that the US has been more successful to provide elements of a hegemonic strategy towards their capitalist classes. It is also important to note that despite differences with the US, the strategy endorsed by the West European capitalist states is also an aggressive imperialist one. Even if it is based upon the centrality of legal forms and conventions, it also includes the liberalization of markets and capital flows, slashing down on labour costs[6], attacking labour rights, restructuring production and increasing exploitation. And it is worth noting that the EU has been the most advanced case of a collective capitalist project in which the partial abandonment of forms of national sovereignty (for example national currencies) is enforced in order to facilitate unfettered cross border capitalist competition that acts as an ‘iron cage’ of capitalist modernization. However, this approach has certain limits and it is very difficult to refer to common European interests as Gowan does (Gowan 2000: 23). The adoption of the common currency policy does not mean the creation of a European supra-state with a common European policy. The states which participate in the common economic policy have adopted that direction due to their own interests. That direction does not rule out inter-imperialist rivalries,. The divisions in the EU concerning the war in Iraq have been very eloquent. In fact there are important differences among the European states about the orientation of the EU, and sometimes the EU looks more like a flexible institutional umbrella under which different national bourgeois strategies operate, than a unified political centre.

2.2.5 The current economic crisis

And it is in light of the above that we must asses Gowan’s theorization of the current economic crisis. It is difficult to disagree with Gowan’s observations concerning the ‘New Wall Street System’ and the aggressive financial strategy of consciously blowing bubbles and then bursting them as a means to increase earnings, finance the expanse of the economy and also secure the predominance of American capital in the world money markets. It is equally difficult to disagree that the current crisis emerged at the centre of the contradictory character of modern finance. But we cannot accept his distinction between a ‘real’ economy in chronic productivity stagnation and an over-expansion of fictitious money capital. What is needed is a more dialectical approach that will address the question of the temporality of finance, its tendency to pre-validate future labour as socially necessary, and the relation between the financialization of the economy and the restructuring of capitalist production. This will offer the possibility of a theorization of the current crisis beyond the simple observation of disequilibrium between industry and finance.

We think that Gowan tended to underestimate the extent of the productivity gains of US industry during the past decades when he referred to an exaggeration of US productivity (Gowan 2009: 26). As we explained earlier we think that compared to the EU the US managed to have greater productivity gains, even if this did not lead to fully overcoming the problem of over-accumulation.[7] We also think that at least in the short term there is not going to be some major challenge for the countries of the capitalist core to the hegemonic position of the US. This will require not only better economic performance from the part of any potential challenger but also a new paradigm for the whole global economy, in the sense that the US exemplified both the post World War II fordist expansion and the combination of capitalist restructuring and financialisation of the past two decades. For the time being the EU bourgeoisies seem to be more preoccupied with taking advantage of the current recession as a means of ‘economic terrorism’ against their working classes in order to push forward a new round of flexible work, austerity and privatizations, than with actually offering a strategy out of the recession, whereas China, despite its rising importance cannot be considered to offer at the moment a alternative for capitalist core countries.

Our final point of criticism is that Gowan should have given more emphasis to the class character of the solutions that have been proposed as a way out of the current recession. In the absence of a strong union movement and a mass anti-systemic left, one can expect a move towards more aggressive austerity, unemployment and restructuring of production. Only a revitalization of social struggle and radical political militancy and a deepening of the contradictions of neoliberal hegemony can force a major change of policy and some form of compromise favorable to labour.

2.2.6 The inadequacy of the notion of empire

We have certain reservations about the notion of modern world-empire that Gowan tried to introduce. We do not disagree with the way he distinguishes it from juridical empire and we think that he correctly describes the special characteristics of the international system (especially the insistence on the importance of formally sovereign states) and the requirements for achieving hegemonic position (that is the ability to cater about the class interests of the capitalists in the other core capitalist states in order for them to recognize the American leadership). However, as we have already noted, we do not think that the notion of empire can be adequate for the specifically capitalist international system and we think that the notions of imperialism and hegemony are more fruitful theoretically.

Also we have certain reservations concerning the notion of Empire-state used by Gowan in the article on the theory of the world systems (Gowan 2004). We think that there are certain limitations to the use of the notion of Empire as a way to describe the American predominance in the international system because it lacks the theoretical rigor that a theory of the capitalist international system requires. The reason is that empires (the old empires of the East, the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, and the Holy Roman Empire) were based on pre-capitalist social relations of production that made territorial expansion and some form of direct rule necessary for the continuing surplus extraction for the imperial state (Wood 2003). Modern-time colonial empires, although they were based upon capitalist social relations in the centre, also involved some form of territorial expansion and direct rule and they represented a transitory form towards the emergence of a truly capitalist international system (Σωτήρης 2003).

On the contrary, modern imperialism is based upon the principles of formal national sovereignty and the capitalist national state is its main locus of social reproduction. Even the savage and criminal occupation of the once sovereign Iraq by the US and its allies is not taking place with the aim to annex Iraq to the US, and is not creating a formal colony, even if the Americans are using the old techniques of colonial administration (the search for collaborators, the anti-insurgent brutality, the use of the Kurds in a variation of the old British ‘divide and conquer’ strategy). The addition of the adjective ‘informal’ is not enough to distinguish modern imperialism from empire-building. And although lexically imperialism derives from empire, we think that we can keep the notion of imperialism to describe the political, economic and ideological practises and strategies of the capitalist states as a result of the internationalization of capital and the tendency of capital to expand beyond national borders, without reference to empires. And if we want to describe the position of the US, we can talk about hegemony or a hegemonic position in a complex, contradictory and hierarchal system of national states (Sakellaropoulos- Sotiris 2008).

2.2.7 Modern protectorates?

The same goes for Gowan’s characterization of the other capitalist states as protectorates. We can accept the notion of protectorate in a descriptive sense, as a way to describe the interventionist character of American post-1945 policy, the hierarchal character of the international system, and the way the US took advantage of the systemic threat posed (or at least projected) by the Soviet Bloc, but we think that as a theoretical notion it fails to explain the particular dynamics and power relations of an international system based upon formal sovereignty. It can also create confusion since from the 1990s we have seen the emergence of a new wave of modern protectorates, or protectorate-like forms of administration in crises zones: Bosnia, Kosovo, Iraq.

There are various problems with Gowan’s conception of American protectorates after WWII. His position is that the US created a protectorate system which covered the entire capitalist core. That means ‘a set of security alliances between the United States and other states under which the US provided external and, to some extent, internal security to the target state, while the latter gave the US the right to establish bases and gain entry for other of its organizations into the jurisdiction of the state’ (Gowan 2002: 2) The result was a system of political domination ‘that approached political sovereignty over the way the protectorates related to their external environment in the sense of that term used by Carl Schmitt: sovereign is the power which can define the community’s friends and enemies and can thus give the community its social substance (in this case, American- style capitalism)’ (Gowan 2002: 2)

Under this light we must make four observations on Gowan’s position. First of all, Gowan insists on the use of the term ‘protectorate’. Our opinion is that each term has a specific content, so it is not accurate to describe imperialist states like the UK or France or Japan as protectorates. According to the international law, protectorate is the case where a state surrenders part of its sovereignty to another state, especially its control over foreign and security affairs but nominally retains its independence, so it is a different case from the colony (Columbia Encyclopedia 2001). Such cases were that of Egypt in WWI (Britain’s’ protectorate), Cuba before the abrogation of the Platt Amendment (1934) (American protectorate). Monaco is still a protectorate of France, San Marino a protectorate of Italy, Andorra is a Spanish and French protectorate since the 13th century etc (Krasner 2001: 244). After the WWI, protectorates are the outcome of a war where the winners determine the future of the losers and especially of some parts of their territories. The content of the term has been modernized and has become a relation between a strong and a weak state or a area which is not recognized as a state (New Dictionary… 2002) or, in a more simple way, a relation of protection and partial control assumed by a powerful state vis-a-vis a dependent state or a region (The American… 2000). There is, also, a very recent question about the status and of cases like Bosnia, Kosovo or Iraq. But all these have nothing to do with cases like the post war era when the Allies imposed a particular regime for the losers of the war and especially for Germany and Japan. In any case this regime did not concern their policy of foreign affairs but their system of security. There was, without any doubt, a lack of sovereignty for these countries but it is too extreme a view to call them protectorates. Even more, states like France, Britain, Canada or Italy had nothing in common with European mini-states like Andorra or Monaco. The hegemony and the influence of the US did not take the form of complete loss of sovereignty or of creation of relations of dependence.

So, our second observation is that it is necessary to clarify the notion of sovereignty. Sovereignty is not an absolute notion but a relational one. There have always been strong and weak states, and always – depending on the balance of power – the former have exerted pressure on the latter. There never has been a stable model of ‘Westphalian’ relations, the class struggle led to many deviations from it. There have always been many asymmetries of power which drove the stronger actors to engage in various forms of pressure or coercion. As Krasner notes ‘weaker states have been more subject to external imposition and coercion and have been more likely to enter into contractual arrangements that violate their autonomy’ (Krasner 1995/6: 148). It is obvious that after WWII stronger states exercised pressure to the weaker ones. There is nothing unprecedented in that situation and this has nothing to do with the formation of protectorates.

In fact, and this is the third observation we would make, Gowan’s position sometimes tends towards a variation of a theory of dependence. Classical theories of dependence claim that the whole world is divided between Centre and Periphery: Centre is the locus of the developed states and Periphery is the locus of the undeveloped states. This form of division is related to the fact that the economy of the under-developed countries is depended on the development and expansion of the developed countries’ economy. This is the result of the political domination of the strong states and the unequal exchange between rich and poor nations[8]. Gowan’s specific contribution is that he claims that there is only one superpower after WWII, the US, which transform former independent states to protectorates creating a new form of dependency[9]. However the real problem is not to describe the differences between strong and weak nations but to explain the reasons why the less strong states formed alliances with the US. The answer of this question does not have to do with a tendency of their elites towards obeisance to the world master, but to the domestic factors which drove the national ruling classes to make alliances with the US. In other terms, the problem is not the unequal exchange or the other elements of the dependency theory but the common capitalist interest, directed against ‘their’ national working classes and also against the regimes of ‘actually existing socialism’, which conditioned bourgeois policies all over the capitalist world.

In our view, there is no doubt that imperialism signifies uneven development. But uneven development does not mean dependency. Uneven development is the necessary outcome of the complex history of the emergence and domination of capitalism in different parts of the world, resulting to the creation of antagonistic social capitals. Competition between capitals in the international plane is necessarily state-mediated, the state’s role being to guarantee the interests of the capitalists as a whole - and this leads to inter-imperialist rivalries. Under this light there were not any protectorates in the post WWII era, but a hegemonic state, the US; within its strategy the other imperialist states, as well as the less developed capitalist states, can recognise that their particular interests are also recognised. Hegemony does not rule out intra-imperialist rivalry or difference in regional strategy. The different positions adopted by American, French and British governments during the Suez crisis provide an example and so does the reluctance of the French and German governments to fully endorse the American attack on Iraq in 2003.

2.2.8 The question of multinationals

We think that Gowan does not pay enough attention to the fact that the whole balance of forces in the international system is internalized in each capitalist state since the incorporation of foreign capital into the hegemonic power bloc of a capitalist social formation leads to an induced reproduction of the contradictions in the international system. The issue of the, so-called, multinational companies is of course too complex to be the subject of any kind of extensive analysis in this article. We will confine ourselves to supporting Hu’s view that when a multi-national enters a foreign market it does so under a national sign (Hu 1992). However, from the moment it starts functioning in the new location, things become more complicated. The company in question is transformed into a fraction of the national capital of its host country. It is obliged to function within the institutional and social boundaries of its new environment, and at the same time it is transformed into a new player in the state field (Panitch 1998). In effect, the capital identified as foreign belongs to the total social capital of a specific social formation, at the same time maintaining a special relationship with its country of origin. This special relationship is also reflected in special agreements between the country of origin and the host country. In any crucial conjuncture the affiliate company knows that it will have the support of the mother state, testifying to the power equilibrium taking shape within the imperialist chain and its influence inside the various social formations. What does this mean for the theory of State? Firstly, that in all cases companies have a national identity and whatever problems they face are solved through state intervention. Secondly, that the entry of foreign capitals into a social formation has a restructuring effect on pre-existing social coalitions (Panitch 2000:8), thus forming a new economic and financial landscape.

In this sense many of the strategic divergences discussed by Gowan are internalized in each core capitalist formation. Under this light there is a real social basis for the current American strategy within the major capitalist states and this can explain that there are always voices of support for US policies in their respective political systems.

3. Conclusion

During the 2000s the return of the notion of imperialism as a way to describe the international system has been a welcome theoretical and political change. The work of Peter Gowan, which in a way preceded current theories of the ‘new imperialism’, has been an important effort to explain the US strive for world supremacy and the link between political economy and interstate relations. But the question of a comprehensive theoretical account of modern imperialism remains open for Marxists. What is needed is not just a mixture of Marxist economics and a more or less Realist conception of interstate conflict and hierarchy, but an attempt to rethink the dialectics of capitalist accumulation, state form and class strategy, both at the national and the international level. Such an attempt at theorizing modern imperialism as modern capitalism is also necessary political. It will help transform the anger against war and imperialist atrocities into a collective struggle against capitalist relations of exploitation and domination. The fact that Peter Gowan will not be able to contribute more to this ongoing debate among Marxists is surely a great loss and reason for sadness. That is why continuing and deepening this debate is the best way to honour his memory.

Bibliography

Amin S., 1976, Unequal Development: an essay on the social formations of peripheral capitalism, New York: Monthly Review Press.

Ark Van Bart, Robert Inklaar and Robert H. McGuckin, 2003, ‘ICT and Productivity in Europe and the United States. Where do the differences come from?’, CESifo Economic Studies 49, 3: 295-318.

Barrow W. Clyde, 2005, ‘The return of the State: Globalization, State Theory, & the new Imperialism’, http://www.psa.ac.uk/2005/pps/Barrow.pdf.

Berger Mark T. and Heloise Weber 2005, ‘Beyond Grand Strategy? Critical Analysis and World Politics’, Critical Asian Studies 37:1: 95-102.

Bergesen Albert and John Sonnett, 2001, «The Global 500», American Behavioral Scientist, 44, 10: 1602- 1615.

Blanke Jennifer and Augusto Lopez- Glaros, 2004, The Lisbon Review 2004: An Assessment of Policies and Reforms in Europe, Geneva: World Economic Forum.

Brenner, Robert 22006, The Economics of Global Turbukence, London and New York: Verso.

Colecchia Alessandra and Paul Schreyer, 2002, ‘ICT Investment and Economic Growth in the 1990s: Is the United States a Unique Case? A Comparative Study of Nine OECD Countries’, Review of Economic Dynamics 5: 408- 422.

Columbia Encyclopedia 2001, http://print.infoplease.com/ce6/society/A0840302.html.

Dichen, Paul 1999, Global Shift, London: Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd.

Duménil Gérard and Dominique Lévy 2004, Capital Resurgent. Roots of the Neoliberal Revolution, Cambridge, Mass. and London, England: Harvard University Press.

Emmanuel Arghiri, 1972, Unequal exchange; a study of the imperialism of trade, New York: Monthly Review Press.

European Economy, 2002, no 6.

European Economy 2006, no 1.

Frank Andre Gunder, 1969, Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America: historical studies of Chile and Brazil, Harmonsworth: Penguin.

Gowan, Peter 1999, The Global Gamble. Washington’s Faustian Bid for World Dominance, London and New York: Verso.

Gowan, Peter 2000, ‘The Euro-Atlantic Origins of Nato’s Attack on Yugoslavia’, in Tariq Ali (ed.), Master’s of the Universe? Nato’s Balkan Crusade, London and New York: Verso: 3-45.

Gowan, Peter, 2001, ‘Neoliberal Cosmopolitanism’, New Left Review, 11: 79- 94.

Gowan, Peter 2002, ‘The American Campaign for Global Sovereignty’, in Leo Panitch and Colin Leys (eds.), Socialist Register 2003 Fighting Identities: Race, religion and ethno-nationalism, London: Merlin Press: 1-27.

Gowan, Peter 2004, ‘Contemporary Intra-Core Relations and World Systems Theory’, Journal of World-Systems Research, X, 2: 471-500.

Gowan, Peter 2004a, ‘Triumphing toward International Disaster. The Impasse in American Grand Strategy’, Critical Asian Studies 36:1: 3-36.

Gowan, Peter, 2005, ‘Economics and Politics within the Capitalist Core and the Debate on the New Imperialism’, http://www.ie.ufrj.br/eventos/seminarios/pesquisa/economics_and_politics_within_the_capitalist_core_and_the_debate_on_the_new_imperialism.pdf.

Gowan, Peter 2005a, ‘America, Capitalism and the Interstate System’, Critical Asian Studies 37:3: 413-432.

Gowan, Peter 2009, ‘Crisis in the Heartland. Consequences of the New Wall Street System’, New Left Review 55: 5-29.

Hu Yao- Su, 1992, «Global or Stateless Corporations Are National Firms with International Operations», California Management Review, 34, 2: 107- 126.

Krasner, Stephen, 1995/96, «Compromising Westphalia», International Security 20, 3: 115- 151.

Krasner Stephen, 2001, ‘Abiding Sovereingty’, International Political Science Review 22, 3: 229- 251.

Lenin, Vladimir Illich 1916 [1970], Imperialism the highest stage of capitalism, A popular outline, Peking: Foreign Language Press.

Lenin, Vladimir Illich 1920 [1970], ‘Left - Wing’ Communism. An Infantile Disorder, Peking: Foreign Language Press.

Lenin, Vladimir Illich 1920a [1966], ‘The Second Congress of the Communist International’, in V.I. Lenin, Collected Works, vol 31, Moscow: Progress Publishers: 213-263.

Wood Meiksins Helen 2003, The Empire of Capital, London and New York: Verso.

Milios John, Dimitri Dimoulis and George Economakis 2002, Karl Marx and the Classics. An Essay on Value, Crises and the Capitalist Mode of Production, London: Ashgate.

New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition, 2002.

Nordhaug, Kristen 2005, ‘The United States and Asia in an Age of Financialization’, Critical Asian Studies 37,1: 103-116.

Palat, Ravi 2005, ‘On New Rules for Destroying Old Countries’, Critical Asian Studies 37,1: 75-94.

Panitch, Leo 1998, « ‘The State in a changing world’: Social- democratizing global capitalism?», Monthly Review 50, 5: 11- 22.

Panich, Leo 2000, ‘The new Imperial State’, New Left Review 2: 5-20.

Panitch, Leo and Sam Gindin, 2003-4, ‘American Imperialism and Eurocapitalism: The making of Neoliberal Globalization’, Studies in Political Economy 71/72: 7- 38.

Pozo-Martin, Gonzalo 2006 ‘A Tougher Gordian Knot: Globalisation, Imperialism and the Problem of the State’ , Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 19, 2: 223 - 242.

Pozo-Martin, Gonzalo (2007) ‘Autonomous or materialist geopolitics?’ , Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 20,4: 551 — 563.

Poulantzas, Nicos 1974, Fascisme et dictature, Paris : Seuil.

Poulantzas, Nicos, 1975, Classes in Contemporary Capitalism, London: New Left Books.

Poulantzas Nicos, 1973, Political Power and Social Classes, London: New Left Books.

Poulantzas Nicos 1978, State, Power, Socialism, London New Left Books.

Prashad Vijay 2005, ‘American Grand Strategy and the Assassination of the Third World’, Critical Asian Studies 37:1: 117-127.

Sakellaropoulos, Spyros and Panagiotis Sotiris 2008, ‘American Foreign Policy as Modern Imperialism: From Armed Humanitarianism to Preemptive War’, Science and Society, 72: 2: 208-235.

Santos Dos, Theotonio 1973, ‘The crisis of the Development theory and the problem of dependence in Latin America’ in H. Bernstein (ed), Underdevelopment and Development’, Harmonsworth: Penguin, 57- 80.

Stiroh, Kevin, 2001, Information Technology and the US Productivity Revival: What do the Industry Data Say?, Federal Reserve bank of New York, http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr115.html.

Σωτήρης, Παναγιώτης 2003, «Αυτοκρατορία: Νέο θεωρητικό υπόδειγμα ή μήπως αναπαραγωγή παλαιών αντιφάσεων;», Θέσεις 85: 11-44.

The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourht Edition 2000.

UNCTAD 2006, http://stats.unctad.org/Handbook/TableViewer/tableView.aspx access 21/6/2006.

Vicziany Marika 2005, ‘Peter Gowan’s ‘American Grand Strategy’. An Asian Regional Perspective’, Critical Asian Studies 37:1: 128-139.

Wallerstein Immanuel, 1974, The World Modern System, New York : Academic Press.

World Economic Forum 2008, The Lisbon Review 2008. Measuring Europe’s Progress in Reform, Geneva: World Economic Forum.

[1] See Hilferding 1981; Lenin 1916; Lenin 1920; Lenin1920a; Bukharin 1970; Bukharin 1973

[2] On a more general assessment of the role played by finance in the neoliberal era see Duménil and Lévy 2004.

[3] On this see Milios, Dimoulis and Economakis 2002.

[4]We note that the percentage share of ICT Investment in Total Non-Residential Investment in 2000 in the sector of ICT equipment and software was 29,9 for the US, 16,0 for Japan, 16,3 for Italy, 15,0 for the UK, 16,2 for Germany, 14,4 for France, 21,4 for Canada (Collecchia/ Schreyer 2002: 427).

[5]It is characteristic that the total factor productivity growth in the two high tech producing industries (industrial machinery and equipment, electronic and other electric equipment) was 7,6% and 7,2% per year for 1995- 1998 respectively. In contrast, during the same period average growth rates were only 2,5% for manufacturing as a whole and 1,3% for the non farm business sector (Stiroh 2001)

[6]It is characteristic that rise of the real unit labour cost during 1991- 2005 varied in EU15 between 0,7% and 0,3% and in US between 0,5% and -1,1% (European Economy 2006)

[7] It is worth noting that even Robert Brenner, who has insisted on the persistence of elements of systemic crisis in the world economy during the past two decades, does not deny true productivity gains in the US economy, pointing instead to a crisis of profitability (Brenner 2006).

[8]For a further development of Dependence School’s basic points see, among many others, Dos Santos 1973; Amin 1976; Emmanuel 1972; Wallerstein 1974; Frank 1971.

[9]From this point of view it is not surprising that Gowan expresses a great admiration to World Systems theory. See Gowan 2004.