Social stratification among immigrants in Greece

Social stratification among immigrants in Greece

Spyros Sakellaropoulos[1]

Department of Social Policy, Panteion University,

Athens, Greece

Abstract

Greece, especially after the fall of so-called “existing socialism”, has been transformed into a recipient country for immigrants. An examination, employing Marxist methodology, is undertaken of the social stratification of the foreign labour force in Greece before (2001) and during (2017) the crisis. The changes are highlighted and their causes investigated. In addition to this, a comparison is made between the social stratification of the country's total workforce and that of the foreign workers (2017), and an interpretation offered of the differences that emerge.

Key words: social stratification, immigrants, Greece, social classes, social disparities

- Introduction

Greece is a country that for many years (1870-1970) was characterized by significant outward flows of labour. There has nevertheless been a limited inflow of foreign workers dating back to the establishment of the Greek state when foreign nationals began to be employed either as staff in embassies or as specialized technical personnel in a number of different, foreign principally, enterprises. In the formal sense of the term, Greek subjects of the Ottoman Empire living and working in metropolitan Greece could be added to this number.

But the first time that workers at a low level in the labour hierarchy came to Greece was in the 1970s. They were for the most part of Pakistani origin because a relevant agreement between Greece and Pakistan was signed for them to work initially in the Skaramangas shipyards, and employed primarily in construction. They were followed in the 1980s by Filipino nationals engaged as home helps.

After the fall of existing socialism citizens of former socialist countries very soon started coming to Greece, first and foremost Albanians, but also Turks and Egyptians.

The reasons why foreign workers are judged to have chosen Greece as place to settle are the following:

- A number of foreigners use the country as an intermediate stage on their way to a more economically developed European country. This is assisted by the fact that Greece has both land and sea borders and is a crossroads between two continents (Georgarakis 2009, 37).

- The fact that Greece was already a member of the then EEC in the 1980s and since 2002 has been a member of the European Monetary Union has in itself been conducive to attracting immigrants.

- The morphology of the Greek economy itself possesses peculiarities generating key prerequisites for the absorption of a low-skilled workforce: a large number of small and medium-sized enterprises[2], a broad agricultural sector, a developed illegal economy. (Georgarakis 2009, 37-38).

With the exception of a small number of foreign workers who, as in the period prior to the 1970s, were employed in positions requiring occupational skills and a high level of education (working in subsidiaries of multinational companies, diplomatic staff, employees of international organizations), the vast majority of foreigners in 1991 worked in construction (primarily Albanians, Poles, Turks) in the metals sector (Egyptians, Pakistanis) in cleaning and the food industry (Thais, Poles, Africans), but also in other sectors such as trade, health, manual work in industry, etc. (Katsoridas 1996, 6). Three decades later, above and beyond the Albanians who are employing in almost all sectors of the economy, accounting for about 50% of the total number of foreign workers (see below), the relevant 2013 study of the Ministry of the Interior indicated that there are numerous migrant women from Bulgaria, the Philippines, Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, working as domestic helps, Egyptians employed in the fishing and textile industries, Pakistanis engaged in manufacturing, construction and services, Indians working in agriculture and stockbreeding (General Secretariat of Population 2013, 33-35).

2.Some demographic – sociographic data

Data from the National Statistical Authority shows that the number of foreigners in the population as a whole rose sharply between 1971 and 2011, from 92,568 people in 1971 (1.05% of the total population) to 171,424 in 1981 (1.76% of the total population), to 797,093 people in 2001 (6.97% of the total permanent population) and from there to 911,029 people in 2011 (8.43% of the total permanent population) (Kapsalis 2018, 39)

This is undoubtedly a significant change, highlighting Greece as a host country of immigration, as opposed to its past history, when tens of thousands of Greeks left every year for the US, Germany, Canada, Belgium and other countries. The fact that there is a proportionally large concentration of foreigners in Greece is also apparent from the comparative data (2005) of the Centre of Research and Analysis of Migration where Greece, with 7.3%, is fifth among twenty European countries in the percentage of foreigners in the population, Switzerland coming first with 19.3% followed by Germany with 8.9%, Austria also with 8.9% and Belgium with 8.4% (Robolis 2007, 61).

As for national origins, in 2011 the highest proportion, 52.7%, of the foreigners living in Greece had Albanian citizenship, 8.3% Bulgarian, 5.1% Romanian, followed by 3.7% Pakistani and 3% Georgian. In the second quarter of 2017 the distribution of aliens by economic activity was 21.4% in accommodation and catering, 14.3% in trade, 13.3% in agriculture, 12.8% in construction and 12% in processing (Kapsalis 2018: 84-85).

In the field of individual occupations, in 2008 56% of non-national males were skilled workers, 20.6% unskilled workers, 8.0% operators of fixed industrial installations and machine operators and 8.0% employees in the service sector and sales. Correspondingly, 58% of female foreign workers were unskilled workers, and 26.9% employed in small-scale sales and provision of services (Kavounidis 2012, 90).

Last, but not least, in terms of net monthly earnings of foreign workers in 2008, 32.8% earned up to € 750- or less than the then lowest salary of € 761, 35.3% earned between € 751 and €1,000 and only 12.9% received over € 1,000. Moreover, 14.5% did not respond to the relevant question included in the survey by the Greek statistical authority (Kavounidis 2012, 97).

3. The theoretical framework

Within the framework of an article focused on the stratification of the foreign workers in Greece it is not possible to refer extensively to theoretical issues of social class theory, which we have analyzed in detail in other work (Sakellaropoulos, 2014). For this reason I will simply mention certain aspects of our theoretical findings, choosing not to embark on more exhaustive discussion, whether inside or outside the Marxist schema.[3]

In my opinion, Lenin's definition is as pertinent as ever in clarifying the multifaceted problem of defining social classes: ‘Classes are large groups of people which differ from each other by the place they occupy in a historically determined system of social production, by their relation (in most cases fixed and formulated in law) to the means of production, by their role in the social organization of labour, and, consequently, by the mode of acquisition and the dimension of the share of social wealth of which they dispose’ (Lenin 1977, 13). I might be noted that in Lenin’s definition there is a co-articulation of three criteria: a) position in relation to the means of production, b) position in the social division of labour, c) means of acquisition of – and level of – income (Bensaid 1995, 203).

The common denominator traversing these three criteria in Lenin’s definition is the phenomenon of exploitation. The possessor of the means of production exploits the person who possesses only labour power, because the possessor pays the labourer less than the value of the work. However, in order for this social relation, derived from the possession of capital, to be reproduced (after all, this is why Marx claimed that capital is primarily a social relation), some structural characteristics must be shaped in the production process that will facilitate circulation of capital and create the hierarchical structures necessary for working discipline to become attainable.

Therefore, what is elaborated is an internally intricate but also externally pyramidal organization of production wherein, for the relations of exploitation to be implemented, relations of domination are also absolutely essential. In this sense, exploitation and, secondly, relations of domination, especially the way they are articulated into a social structure (Croix 1984, 94), are the agents in formation and reproduction of social classes.

The conclusion is that the foundations of prevailing social arrangements are to be situated in the existence of relations of exploitation and domination, yet membership in a particular class depends firstly on who owns the means of production and secondly on each person’s position in the division of labour and the amount of social wealth a person extracts.

Nevertheless, it must be made clear that the economic element (relation to the means of production, level of income, etc.) is the most important and decisive, albeit not the only, element. The ‘position occupied by individuals’ may be determined by reference to both the political and the ideological elements that contribute to shaping the relations of domination. Thus the top echelon of the state bureaucracy: members of government, high-ranking military personnel, etc., belong, by virtue of their position in the machinery of power, to the bourgeois class.

The intervention of capital and the state in maintaining and reproducing relations of exploitation is continuous and embraces all levels of social activity. The reason for this is that capital does not only exploit workers economically but also exercises power over their functioning in the workplace, from the moment that it determines what and how they will produce. At the same time, through the Ideological Apparatus of the State,[4] it integrates them ideologically as the workers accept the terms of their political and economic exploitation as the ‘natural’ result of the exchange of ‘wage’ and ‘labour power’ equivalents. To put it differently, the framework of the relations of exploitation is reproduced by the political and ideological mechanisms functioning, within which capitalist power is also reproduced, not through the realization of surplus value but through reproduction of managerial and executive labour.

It should be stressed that classification of the various agents in social relations is no static, cerebral process. On the contrary, social classes are defined through an antagonistic relation: the class struggle (Balibar 1985, 174), which determines the movement of history. This means that class struggle results in transformations in the positions of social categories and social strata in such a way that there is no one-to-one correspondence between assigned social class and membership in a particular professional category. Nothing is exempt from change (Aronowitz 2002, 56).

With these general definitions as our starting point, we proceed to make some conclusions about the most significant characteristics of the bourgeois class: it is the class that directs the capitalist productive process, and it always, with a view to its own interests, defines the context and the hierarchies of the social praxis dominated by capital (Bihr 1989, 88-89). Its position is based on owning the means of production and subjecting society to its power. At a level of high abstraction, its members are defined as non-productive exploiters/possessors/extractors of surplus labour-cum-organisers of the mechanisms of domination (Johnson 1977, 203).

The working class is deprived of possessing the means of production, but it performs all those practices that are aimed at furthering reproduction of capital and reinforcing social power. It neither possesses control of, nor is able to influence the context of its labour. It simply plays an executive role within the social division of labour (Bihr 1989, 90). In a more abstract away we could define the working class as consisting of exploited/non-possessors/producers/wage-earners enduring the constraints imposed by the mechanism of domination (Johnson 1977, 202-203).

Nevertheless, the existence of the two basic classes of the capitalist mode of production does not mean that there are not other social classes in a society. Only at a high level of abstraction – that of the mode of production – is it possible to speak of only two classes. At the national social formations level, the number of classes is greater precisely because the different historical development of each formation includes more modes of production but also ‘a) because there are also more modes of production, that is to say forms of organization of the productive process, which are not based on the appropriation of surplus labour, on exploitation, and b) because some of the class functions of the dominant class are normally delegated to social groups that are not part of the dominant class (are not owners of the means of production)’ (Milios 2002, 64). Τhis social class we name the petit bourgeoisie occupies, in the active sense of the term, a position between the working class and the bourgeoisie.

Τhe basic characteristic of members of the petit bourgeoisie is that their income is greater than what is necessary for reproduction of their labour power, irrespective of how this is achieved. Sometimes it is realized through the appropriation of surplus value and sometimes through earnings that exceed the cost of reproduction of their labour power. Above and beyond that a second characteristic is that they are not exclusively subjected to domination by other classes. The traditional petit bourgeoisie exerts power over the workers it employs; the new salaried petit bourgeoisie is subject to the power of capital but also exerts power over the working class, whereas the self-employed (who are also to be included in the new petit bourgeoisie) neither exert power nor are subjected to it.

Further refining this line of thought we could argue that the petit bourgeoisie is divisible into the traditional petit bourgeoisie and the new petit bourgeoisie. The traditional petit bourgeoisie includes owners of small manufacturing companies, small family businesses and small commercial enterprises not involved with extended reproduction of capital (that is to say employing up to nine workers).[5] The new petit bourgeoisie is comprised of all those who work as either self-employed professionals or salaried employees engaged in supervising and organizing the work system, realizing surplus value, overseeing the cohesiveness of capitalist operations or, finally, legitimizing the terms of reproduction of existing social relations.

Nevertheless, if the theoretical approach of social stratification is to be comprehensive, it is necessary to refer to cross-class social categories, such as farmers, civil servants and intellectuals, besides the basic class divisions and the petit bourgeoisie.

Farmers fall into the above category, because despite being involved in land cultivation, they differ from each other depending on the expanse of the land they cultivate and the extent to which they employ land laborers

As regards the agricultural strata and small landowners, i.e. those who, in Greece, are proprietors of up to 50 acres, they are the less affluent layers of rural society and do not employ wage labour. Correspondingly, proprietors who make limited use of wage labour in cultivation of their land,. those who in Greece own between fifty and two hundred acres and are engaged in simple reproduction of their capital (Panitisidis 1992) belong to the intermediate rural strata, whereas those who employ a wide range of salaried employees, those who in Greece are proprietors of more than 200 acres, which enables them to proceed with extended reproduction of capital, belong to the wealthy rural strata.

Another stratum that is distinctive for its cross-class characteristics is that of the civil servants, because a civil servant may be employed in very different sectors. A significant sector employed in public enterprises such as processing, energy and water supply, communications, transport and banks, are productive working people (Meiksins 1986, 17), because they are paid less than the value of their work when they exchange their labour power for capital. In that sense individuals in this category are both productive workers and people exploited by the collective capitalist and to be included in the working class.

On the other hand people working in education, in cases where education is provided free, and administrative personnel in the various public bodies and ministries are not productive workers but, with the exception of senior and middle-ranking officials in the ministries, the armed forces, university professors and civil servants who are members of the new petit bourgeoisie (engineers, lawyers, doctors) and work in the public sector, belong to the working class for the following reasons:

1) They do not own their means of production.

2) Their surplus labour is subject to extraction.

3) They perform the function of the collective worker (Carchedi 1977, 134).

4) They are remunerated with a salary which is determined by state income policy (Lytras, 1993, 98), which is equal to the value of their labour power, because it correlates directly with salaries in the private sector (Bouvier, Ajam ανδ Mury 1963, 73) which tend not to rise above the level of reproducing their labour power.

Therefore, civil servants as a collectivity, united essentially by the institution of tenure, are a cross-class entity. The great majority can be classified as working class; the middle-ranking officials in the ministries, public enterprises and the military, and university teachers belong to the petit bourgeoisie, and the heads of administration (political, military, academic) and the managers of state-owned companies belong to the bourgeoisie by virtue of the dominant position they occupy within the collective capitalist known as the State.

Another category of individuals not belonging to a specific social class are the intellectuals. This is not a professional category but a social layer, a large number of which are salary earners. Gramsci, who considered the question in depth, regarded the action of intellectuals as confined to the realm of the superstructure and pertaining to both the ‘private sphere’ and ‘political society’. Those who are in the private sphere are concerned primarily with the functioning of their hegemony, and in the latter are concerned with the management of their direct domination (Gramsci 1972, 62). There is an internal graduation to their activity. The highest rung is occupied by individuals who have undertaken the formulation, organization and systematization of the dominant ideology (Gramsci 1972, 63) and who belong to the bourgeoisie. The lower levels include executive officers whose concern is the generation and promotion of consent and discipline and who are to be included in the petit bourgeoisie.

Workers who contribute intellectual labour constitute a separate category. They produce surplus labour/value for their employers (e.g., educators in the private sector). These ‘intellectual workers’, from whom surplus labour/value is extracted, belong to the working class. They do not count as ‘intellectuals’ because they are charged not with planning and organizing consent but rather with implementing the terms of its realization.

4.The social stratification of the foreign labour force

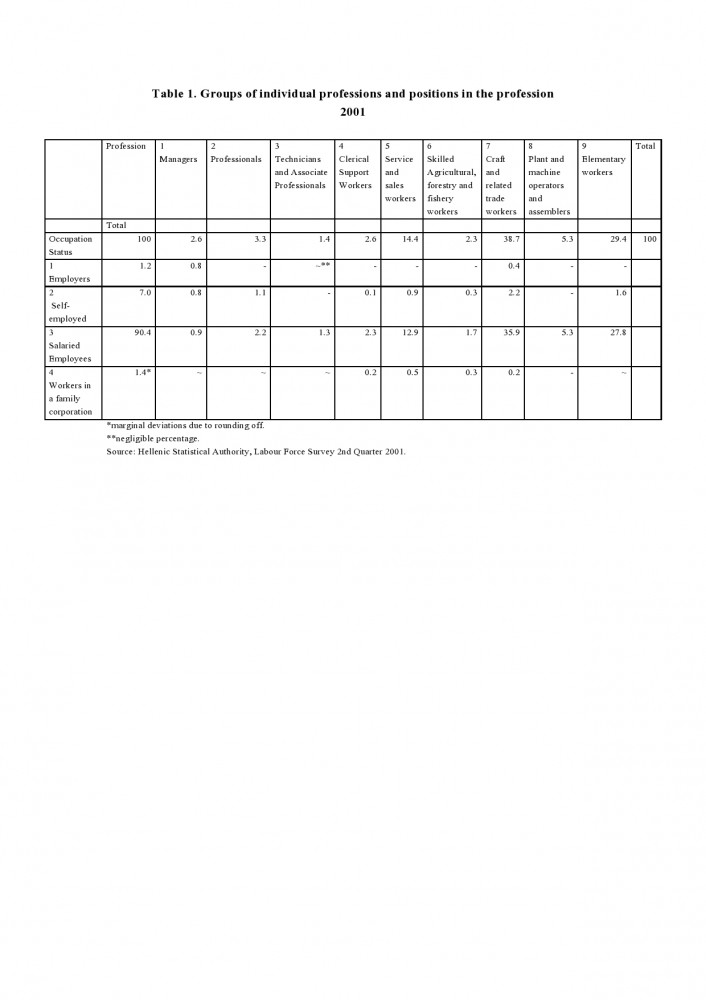

On the basis of the theoretical framework that has just been presented, we can proceed to an assessment of social stratification of the foreign immigrants in the Greek society at 2017.Above and beyond the preceding theoretical inferences we propose to utilize existing data from the Labour Force Quarterly Data on the mode of employment of the workforce (occupation and position in the workplace) in addition to the methodology has been adopted in a preceding study (Sakellaropoulos 2014) which we cannot present in detail here. The final result for 2001 can be seen in this table

It is estimated that the totality of employers (1.2% of the total number of foreign workers in Greece) belong to the traditional petty bourgeoisie because, on the one hand, there is no significant number of foreign employers employing ten people or more and so qualifying to be regarded as part of the bourgeoisie and, on the other there are no foreign landowners also employing farm workers and so, depending on the size of their property, belonging either to the rich or the medium rural strata.

The self- employers comprise 7% of the total and can be divided into the following three categories:

The first category includes people employed in agriculture (0,3% of the total). They are farmers who do not employ a salaried workforce and they simply manage to subsist, so they belonging to the social strata of poor farmers.

The second category includes members of the new petty bourgeoisie, that is to say all branches of the liberal professions who do not experience exploitation or domination and who together comprise 5,8% of the total. The third group consists of small entrepreneurs (small traders and small sellers) who do not exceed 0,9% of the total and are to be included in the traditional petty bourgeoisie.

The category of Salaried Employees, which is also the most populous statistical category (90.4% of the total), consists primarily of members of the working class but also includes members of the bourgeoisie (0.9% of the total employed as managers - 1,619 persons in absolute terms - working in around 35[6] 0 multinational companies operating in the country), and the new petty bourgeoisie (2.2% of the category “professionals” and 1.3% of the category “technicians and associate professionals”). From that point on, the remaining 86.0% are members of the modern working class, with the new petty bourgeoisie class coming to 3,5% and bourgeoisie to 0,9%.

Workers in a family business account for 1.4% of the total, primarily consisting of those performing ancillary tasks in trade (0.5% of the total) and secondarily of agricultural workers (0.3% of the total), some as Clerical Support Workers (0,2% of the total) and some (0,2% of the total) who are working as Craft and related trade workers. Therefore, this 0.3% should be included among the poor agricultural strata, and 1.1% among the members of the traditional petty bourgeoisie who are not engaged in expanded capital accumulation.

Making the relevant calculations, it emerges that the bourgeoisie accounts for 0.9% of foreign workers, the traditional petty bourgeoisie 3.2%, the new petty bourgeoisie 9.3%, the poor rural strata 0.6% and the working class 86%.

Nevertheless, the question remains of the unemployed foreign workforce, which in the second quarter of 2001 came to 11.4% (Kapsalis 2018, 79). In another study on calculation of social stratification in the Greek population as a whole I distinguished between the unemployed with a tertiary educational degree who were to be included in the new petty bourgeoisie and those who did not and were accordingly classified as working class. In the case of foreigners this is not feasible because, as the relevant research by Lianos and Papakonstantinou has shown, aliens are mostly employing in lower posts within the process of production, even if are highly educated (Lianos and Papakonstantinou 2003, 153-157). The only exception to this is foreign citizens coming from countries in the developed West who, in the event that they lose their jobs, will not stay in Greece to seek new employment but will return to their country of origin. As a result, 11.4% of the unemployed can be regarded as belonging to the working class.

So, appending the 11.4% of the unemployed to the 100% of workers, an index of 111.4 emerges as a new total on the basis of which calculations of social stratification of foreign workers in the country should be made. Making the relevant calculation it emerges that the working class is 86 + 11.4/ 111.4= 87.4%, the bourgeois class 0.9/111.4 = 0.8%, the traditional petty bourgeoisie 9.3/111.4 = 8.3% and the poor farming strata 0.6/111.4 = 0.5 %.

The conclusion that emerges is that the overwhelming majority of foreign workers belong to the working class. They are people coming from their countries to Greece with their only thought being how they can earn some money themselves and send a sum to their relatives in their homeland. Irrespective of their level of education, which is often high (Lianos and Papakonstantinou 2003, 153-157), they do not hesitate to undertake menial work precisely because of the great need to earn money, the amount of which has high purchasing capacity in their countries of origin. A few migrants work as farmers, either as farm hands or by cultivating a small area. There are also a limited, but existing, number of foreign workers who are self-employed. As far as we can see they are people who have managed to acquire a certain basic personal capital that enables them to be something other than wage labour. An even smaller number, who would be classified as traditional petty bourgeoisie, are in a position to secure enough capital to employ workers, usually of their own nationality, and hired to work in light industry and petty trade. Last but not least there is the small number of foreign workers belonging to the bourgeoisie. They are citizens of countries of the developed West who are executives in multinational corporations, whose life and activities bear no relation to the everyday life of the overwhelming majority of other foreign workers.

Let us see now how things have evolved sixteen years later.

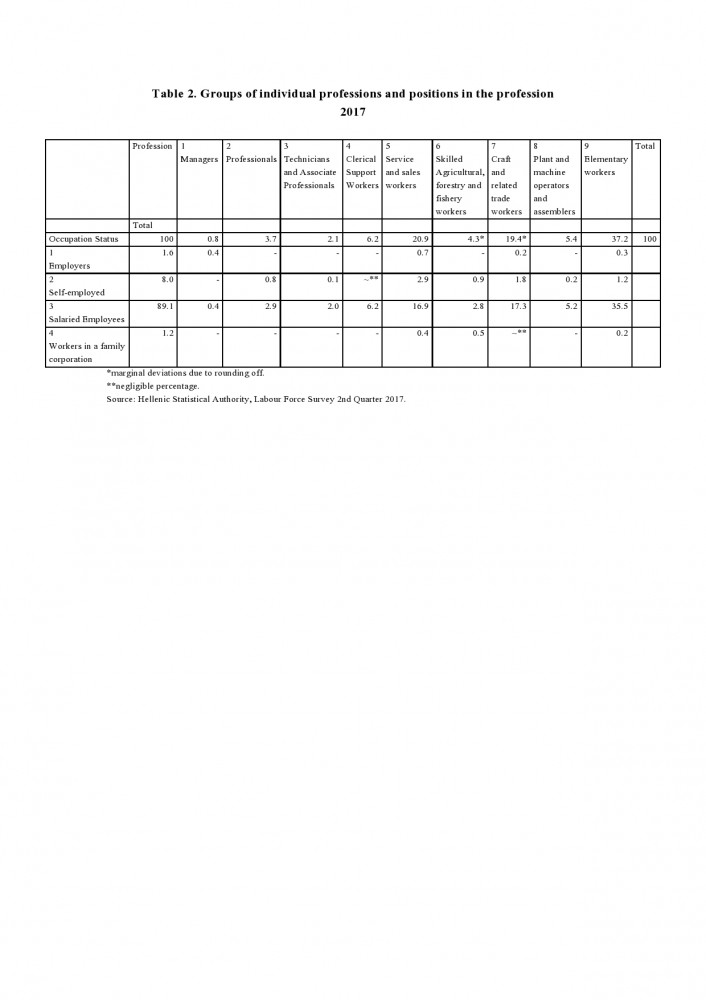

Taking the corresponding data for the second quarter of 2017, one comes up with the following table:

Using the same methodology as that employed for processing the data in Table 1, we are drawing the following conclusions:

All the employers (1.6% of the total number of foreign workers in Greece) are to be categorized as traditional petty bourgeoisie, simply because there is still no significant number of foreign employers with 10 or more people working for them. Nor are there foreign landowners to occupy farm workers.

The self- employers comprise 8% of the total and, as we have already seen, can be divided into the following three categories:

The first category includes people employed in agriculture (0,9% of the total). They are farmers who do not employ a salaried workforce so they belonging to the social strata of poor farmers.

The second category includes members of the new petty bourgeoisie who together comprise 4,2% of the total. The third group consists of small entrepreneurs (small traders and small sellers) who do not exceed 2,9% of the total and are to be included in the traditional petty bourgeoisie.

The category of Salaried Employees, which συνεχίζει να αποτελεί the most populous statistical category (89.1% of the total), consists primarily of members of the working class but also includes members of the bourgeoisie (0.4% of the total employed as managers - 858 people in absolute figures – working in the around 300[7] multinational enterprises operating in the country) and the new petty bourgeoisie (3.7% of the category “professionals” and 2.1% of the category “technicians and associate professionals”. From that point on, the remaining 82.9% are members of the modern working class, with the new petty bourgeoisie class coming to 5,8% and bourgeoisie to 0,4%.

Workers in a family business account for 1.2% of the total, primarily consisting of agricultural workers (0.5% of the total) and secondarily those performing ancillary tasks in trade (0.4% of the total) and some (0,2% of the total) who are working as elementary workers. They are individuals involved in family-run economic activities. Therefore, this 0.5% should be included among the poor agricultural strata, and 0.4% among the members of the traditional petty bourgeoisie who are not engaged in expanded capital accumulation, and there are also 0.2% who belonging to the working class.

Calculations indicate that the bourgeoisie account for 0.4% of all foreign workers, the traditional petty bourgeoisie 4.9%, the new petty bourgeoisie 10%, the poor rural stra 1.4% and the working class 83.1%.

But there too the question arises of the foreign labour that is unemployed, amounting to 25.7% of the total in the second quarter of 2017. Following the same argument as was adopted for the 2001 data, it can be postulated that 25.7% % of the unemployed belong to the working class.

If one adds the 25.7% of the unemployed to the 100% of the workers, an index of 125.7 on the basis of which calculations, here too, can be made of the social stratification of foreigners in Greece. It accordingly emerges that the working class comprises 83.1 + 25.7 /125.7 = 86.6%, the bourgeoisie 0.4/125.7 = 0.3%, the traditional petty bourgeoisie 4.9/125.7 = 3.9%, the new petty bourgeoisie 10/125.7 = 8% and the poor rural strata 1.4/125.7 = 1.1%.

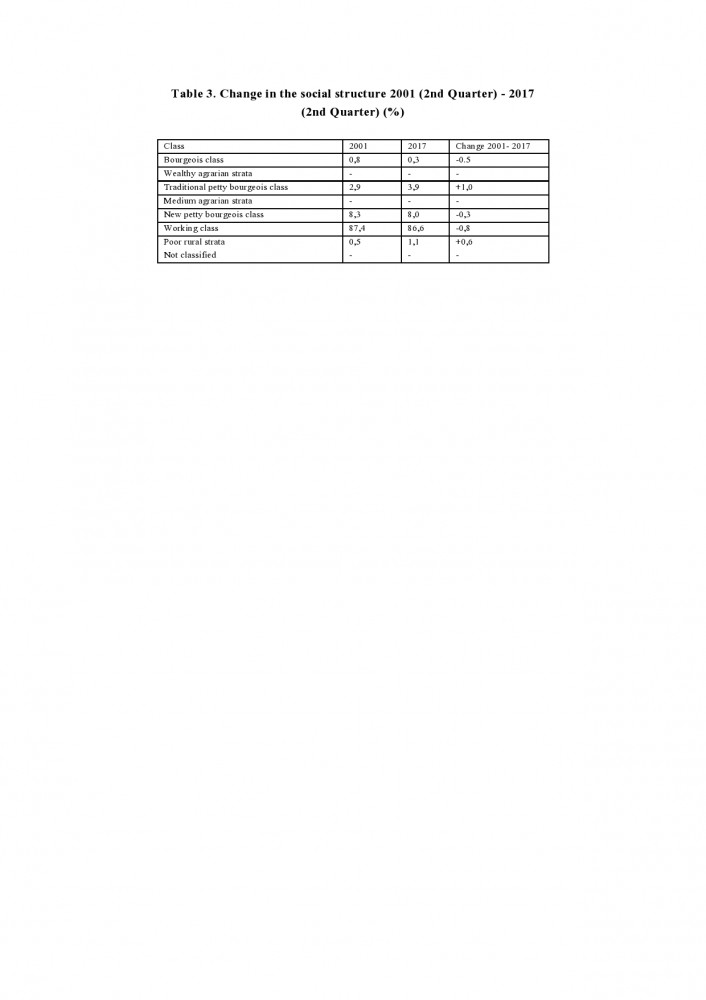

Based on the data for 2001 and 2017, it has been the following table:

It is observed that the bourgeoisie undergoes a significant contraction, attributable to the harshness of the economic crisis which struck the Greek economy, inducing a significant number of multinational companies either to withdraw from Greece or to reduce their activity[8]. At the same time it does not appear that foreigners of non-Western origin are in the habit of establishing enterprises employing more than ten people. This can also be attributed to the severity of the crisis, discouraging any significant degree of financial risk, as well as to repatriation of some of the immigrants, not to mention limitation of the amount of capital obtainable by some of them during their stay in Greece.

In contrast the traditional petty bourgeoisie has seen a real increase on account of their acquisition of some basic capital in the first years of their working in Greece, making it possible for them to achieve some upward social mobility. It is in this context that the rise in the number of poor rural strata can also be understood. These are farmers who thanks to their savings have been able to acquire some small portion of land of their own, but they are not in a position to be able to employ labourers.

The marginal contraction of the new petty bourgeoisie is linked to the aforementioned diminution in the presence of multinationals and the fact that such non-Western foreigners as have succeeded in acquiring some capital have chosen to invest it in small businesses, in the hope that this will contribute to further improvement of their financial situation.

Correspondingly the very slight numerical reduction of the working class can be explained by the tendency towards social ascent of a segment of foreign workers, more or less counterbalancing the withdrawal of executive staff of multinational enterprises belonging either to the bourgeoisie or to the new petite bourgeoisie.

5. Comparison of stratification among immigrants and the entirety of the working population

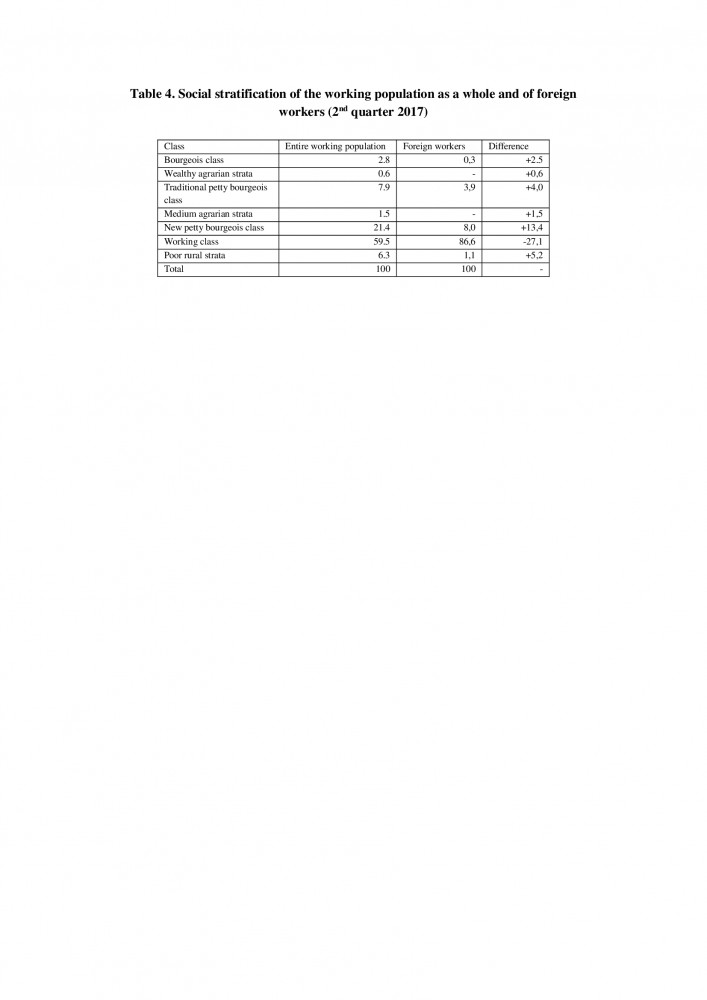

Availing the results from another of our studies on social stratification in the entire working population of Greece (Sakellaropoulos 2019) in correlation with the findings of the present article on stratification among foreign workers in 2017 it is presented Table 4:

The data of Table 4 shows that in all social categories, with the exception of the working class, the number of foreign workers is clearly below the national average. And it is indeed interesting that foreign workers are entirely absent from two categories (wealthy and middle-level rural strata). The latter exposes, on the one hand, their financial incapacity to proceed with purchases of medium-sized and large areas of farmland but also that the brevity of the time they have so far been living in Greece precludes the conclusion of inheritances, crop combinations, etc. Which is why they are the proprietors only of smallholdings, and even that by way of exception. Conversely, Greeks are to be numbered among the poor farmers precisely because of the transfers of small-scale ownership in the agricultural sector in Greece.

That said, there is an evident correlation between the absence of medium and large-scale property and the low proportion of foreigners qualifying for inclusion in the bourgeoisie. It is very difficult for people having lived for ten or at most twenty years in a country whose economy is plagued by an unprecedented economic crisis to be in a position to accumulate enough capital to establish companies with at least ten employees working in them. As indicated, this meagre participation (0.3%) is not from immigrants coming from countries of Eastern Europe and the Third World but rather from executives of multinational companies that have continued to operate in Greece.

It is interesting about the existed little difference from the rate of inclusion in the traditional petite bourgeoisie. For a foreigner it is a sign of upward social mobility to have succeeded in rising above the status of wage labour, joining the ranks of small property ownership. On the contrary, for the Greeks it is a consequence of the crisis and of contraction in the size of many until then larger businesses.

The new petty bourgeoisie is largely associated with the particular functions performed for capitalism by professions such as doctors, engineers and lawyers. In the case of aliens this does not apply: these are people who may not be able to establish their own business but are able to earn a living beyond the framework of salaried employees. That is the reason for this divergence from the national average.

The very significant difference in rates of inclusion in the working class is a reflection, of course, of everything previously mentioned, and at the same time leads to a more general conclusion. The explosion in the number of foreigners in Greece from 171,000 in 1981 to 911,000 in 2011 can be seen from two viewpoints. The former has to do with the significant strengthening of the Greek economy from a highly skilled but low-wage workforce that contributed to the vigorous growth rates observable prior to the crisis. It could also be pointed out that precisely the presence of these people was a factor in delaying the emergence of the crisis. The latter is linked to the way in which the great majority of them have been incorporated into the Greek reality. On the one hand, there was the attitude of the Greek state and a considerable section of Greek society which greeted them with practices of authoritarianism, superexploitation, hostility, contempt - at best with mistrust. On the other hand they themselves were required in a very short time to adapt to the new circumstances, to survive in this hostile climate and in a twofold way to transform their identities: from citizens of their State of origin to migrants, i.e. quasi second-class citizens, and in many cases from people in positions requiring university-level specialization to unskilled labourers.

6.Conclusion

The social history of Greece was characterized by the export of labour for a period of about 100 years (1870-1970). Then, until the onset of the economic crisis, this stopped and a period of limited but real labour inflow commenced. This trend was intensified following the fall of the regimes of so-called “existing socialism”. Within a very brief period of time Greeks would have to become accustomed to living with a significant number of their foreign fellow citizens and the foreign citizens to become accustomed to a quite different, and to a significant extent hostile, social environment.

The jobs made available to them were menial, poorly paid and very often without insurance (in the “black” labour market). The result of this was that in their overwhelming majority - about ninety percent - they were included in the working class. One exception to this trend were foreign workers from Western countries who occupied executive positions in the domestic subsidiaries of multinational companies.

This situation was to be modified in the years of the crisis without, however, changing radically. A section of the workforce coming from the West left as the multinationals they worked for underwent contraction or ceased operations. Above and beyond that, the bulk of the foreign workers from former socialist and Third World states continued to be part of the working class. But there were also limited, but existent, sections that experienced improvement of their social position, finding a place in the strata of petty proprietors (small shop owners, small farmers).

This trend in no way ran contrary to the overall tendencies in Greek society, where there was a dichotomy between Greek and foreign workers. Among the former the so-called middle strata were very much in evidence. In the latter case the prevailing social identity was working class.

References

Alevra, Emilia. 2005. Multinational enterprises in Greece. [in Greek.] http://hellanicus.lib.aegean.gr/bitstream/handle/11610/6113/file0.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y, accessed on 8/19/2018.

Aronowitz, Stanley. 2002. How Class Works. Power and Social Movement. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Atkinson, Will. 2015. Class, Cambridge: polity.

Balibar, Etien. 1985. “Classes” in Dictionnaire Critique du Marxisme edited by Georges Labica and Gerard Bensussan, 170-179. Paris: PUF.

Bensaid, Daniel. 1995. Marx l΄intempestif. Fayard: Paris.

Bihr, Alain. 1989. Entre Bourgeoisie et Prolétariat, Paris: L’ Harmattan.

Bouvier-Ajam, Μaurice and Gilbert Mury. 1963. Les classes sociales en France. Paris: Editions Sociales.

Carchedi, Guglielmo. 1977. On the Economic Identification of Social Classes. London: Routledge.

Croix de ste, Geoffrey. 1984. “Class in Marx's Conception of History, Ancient and Modern”, New Left Review 146: 94-111.

General Secretariat of Population and Social Cohesion. 2013. National Strategy for integration of citizens of third countries. [in Greek.] Αthens: Ministry of the Interior

Georgarakis Nicos. 2009. “Immigration policy. Stances and resistance in the Greek Administration” [in Greek.], in Views on immigration and immigration policy in Greece today edited by Christina Varouxi, Nicos Sarris and Amalia Frangiskou, 33-60, Athens: National Centre for Social Research.

Gramsci, Antonio. 1972. The intellectuals. [in Greek.] Athens: Stochastis.

Johnson, Τerry. 1977. “What is to be known?”. Economy and Society, 6(2): 194- 233.

Kapsalis, Apostolos. 2018, Migrant workers in Greece. Labour relations and immigration policy in the Greece of the memoranda. [in Greek.] Athens: Topos.

Katsoridas, Dimitris. 1996. “Foreign workers in Greece and their living conditions” [in Greek.], Theseis 56: 1-16.

Kavounidi, Jenny. 2012. “Integration of migrants into the labour market” [in Greek.] in Migrants in Greece. Employment and integration into local communities edited by C. Kasimis and A. Papadopoulos, 69-104, Αthens: Alexandreia

Kotzamanis, Viron and Alexandra Karkouli. 2016. “Migrant inflows in Greece over the last decade: intensity and basic characteristics of illegal immigrants and asylum applicants” [in Greek.] Workshop for Demographic and Sociological Analysis 26: 1-7 https://www.tovima.gr/files/1/2016/04/metanaroes.pdf (accessed on 13/10/2018)).

Lenin, Vladimir Ilich.1977. A Great Beginning, Peking: Foreign Languages Press.

Lianos, Theodoros and Panaghiota Papakonstantinou. 2003. Contemporary Migration in Greece: economic investigation. [in Greek.] Athens: Centre of Planning and Economic Research.

Lytras, Andreas. 1993. Introduction to the Theory of Greek social structure. [in Greek.] Athens: Livanis.

Meiksins, Peter. 1986. “Beyond the boundary question”, New Left Review 154: 101- 120.

Milios, John. 2002. “The question of the petty bourgeoisie. A single class or two discrete class aggregations?” [in Greek.] Theseis 81: 59- 80.

Panitsidis, Giorgos. 1992. Approaches to the class structure of our farm economy. [in Greek.] Αthens: Synchroni Epochi.

Robolis, Savvas. 2007. Migration from and to Greece. [in Greek.] Thessaloniki: Epikentro.

Sakellaropoulos, Spyros. 2001. Greece after the Dictatorship. [in Greek.] Athens: Livanis.

Sakellaropoulos, Spyros. 2014. Crisis and Social stratification in 21st century Greece. [in Greek.] Αthens: Topos.

Sakellaropoulos, Spyros. 2019. Greece’s (un) Competitive Capitalism and the Economic Crisis -How the Memoranda Changed Society, Politics and the Economy, London: Palgrave.

Zografakis, Stavros, Antonios Kontis and Thodoros Mitrakos. 2009. Migrant steps in the Greek economy. [in Greek.] Αthens: ΙMEPO (Institution of Migration Policy).

[1] Corresponding address: Aspasias 4, 15125, Athens- Greece, email:sakellaropouloss@gmail.com

[2] It is characteristic that in 2006 81.1% of foreign workers were employed in a company with up to nine people working in it whereas the corresponding percentage for Greeks was 61.3%. Likewise only 2.5% of foreigners worked in companies employing over 50 wage-earners whereas the proportion for Greeks came to 10.9% (Zografakis, Kontis and Mitrakos 2009, 84)

[3] For a recent comprehensive presentation of the basic content of the Marxian and Marxist problematic on the question of social classes, see Atkinson, 2015, 19-39.

[4] For the importance of the role of the Ideological State Apparatus see Althusser, 1976.

[5] For why more than nine workers are needed for there to be extended reproduction of capital, see Sakellaropoulos 2001, 170.

[6] Alevra calculated that 350 multinational corporations had established in Greece (Alevra 2005, 94).

[7] As we have seen, Alevra calculated that 350 multinational corporations had established themselves in Greece. However, the coming of the crisis in Greece has led some multinationals to suspend their operation(Conti Tech, Bolton Group, ILVA, FrieslandCampina) and others to restrict it (Coca Cola, Pepsico, Teva).

[8] It is characteristic that whereas in 2001 99.6 thousand citizens of the developed countries of the West were resident in Greece, this number had fallen to 90.7 thousand in 2011 (Kotzamanis and Karkouli 2016, 2).