Greece at a Crossroads: Crisis and Radicalization in the Southern European Semi-periphery

Greece at a Crossroads: Crisis and Radicalization in the Southern European Semi-periphery

σε συνεργασία με Πάρη Γέρο και Χρίστο Παπαθεοδώρου

Introduction

The Greek crisis represents the deepening of a long systemic contradiction whose origins lie in the 1960s, in the stagnation of monopoly capitalism and the emergence of the South. The industrial centers of the world economy were struck by a crisis of profitability, which was displaced outward in space and forward in time by the financialization of monopoly capital, technological innovations in robotics and information systems, and shifts of industrial production to selected countries in the South, especially East Asia. These shifts and transformations inaugurated a new dynamic of accumulation, which has been driven by predatory financial institutions, a new international division of labor, and, upon the collapse of the Eastern bloc, a security system dominated by the unparalleled firepower of NATO (Amin 2003, Foster 2010, Foster et al. 2011).

Greece is the latest in a long string of countries that have fallen victim to these shifts and transformations. Initially, in the 1980s, the burden of adjustment to global disequilibria was, by and large, borne by the peripheries and semi-peripheries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, which under IMF instruction undertook a unilateral opening to the world economy (Moyo and Yeros 2011). In the 1990s, it was the turn of the Eastern bloc, which was radically reintegrated into the world economy via the same, if not more tumultuous, ‘shock therapy’ measures. The welfare-state systems in the West also began to come under attack at this time, while the world economy as a whole entered a period of slower growth, punctuated by the serial bursting of financial bubbles. But, throughout this period, the centers of the system retained their capacity to evade a major meltdown of their own. This all changed in 2008, when the biggest of all bubbles burst in the US housing market.

Greece is not the first country to be hit by the systemic crisis, but it is the first semi-peripheral country to undergo a sustained process of radicalization. This is in itself a new and significant political fact, given the specific role that semi-peripheries fulfill as systemic ‘shock absorbers’ (Arrighi 1997). Add to this Greece’s participation in a major currency zone, a major regional market, and the planet’s supreme military alliance, and we can see why the political turmoil in this small country can make stock markets tumble everywhere and threaten to set off global chain reactions.

Semi-peripheries in a Systemic Scissors Movement

An important dimension of this systemic transition has been the continuing differentiation among semi-peripheral states. In the 1980s, the hitherto emerging semi-industrialized countries of Latin America were reconverted into export-oriented economies under the weight of debt, entering thereafter a path of slow industrial growth or de-industrialization, along with re-specialization in primary sectors and expansion of services (Marini 1992, Martins 2011). Meanwhile, the Southern European semi-peripheries pinned their hopes on integration into the German-led European industrial and monetary sphere of influence, thus initiating a similar process of industrial stagnation and de-industrialization. However, in the latter case, a hard landing was initially averted by eventual incorporation into a credit-induced growth model, intimately tied to German industrial exports and European and US financial institutions. Both of these groups of semi-peripheries underwent deep financialization, but Southern Europe was spared severe demand compression.

New industrial growth centers also sprouted in Eastern Asia, with an export orientation, but these too would eventually stumble into the trap set by finance capital, which mounted a new assault in 1997-98. The main country that resisted the assault in this case was China, only to emerge as the game changer in global industrial production. Its controlled but sustained opening to foreign capital, and its internal re-organization, went on to push another half a billion workers onto the global assembly line, putting downward pressure on wages in industrial production all around (Minqi 2008).

It is in this global scissors movement, between a technology-intensive Germany and a labor-intensive China, operated by the financial sector, that Greece, and the Southern European semi-periphery as a whole, has finally been caught. Germany’s strategy in the last decade of cutting domestic wages — a policy of “beggar thyself and thy neighbour” in the words of Lapavitsas et al. (2010) — could not but deepen intra-Eurozone disequilibria. The stage was thus set for a major crisis within Europe: the sudden credit crunch ensuing from the US-led financial crisis finally cut through the EU’s fragile fabric. The Southern European semi-periphery, with Greece in the forefront, has now been called upon to adjust and essentially to converge downward, closer to Balkan and Latin American wage levels. In the case of Greece, its crisis has laid bare the fragility of a development model driven by shipping, construction, tourism, and banking capital, and founded on the exploitation of Greek workers as well as a large immigrant workforce — mainly from South Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe — that has been especially subject to super-exploitative relations.

The radicalization that is now in progress in Greece is no longer a rare phenomenon. It is true that in most cases of severe adjustment, radical responses have been eventually controlled, coopted, or smothered, as the cases of Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Haiti, and Honduras have shown. But radicalization has also been leapfrogging around the world, shifting the correlation of forces in domestic politics, as well as regionally, from Nepal and Zimbabwe, to Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador (Moyo and Yeros 2011). The more recent uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East have threatened to do the same.

In all cases where radicalization has taken effect, it has constituted a robust challenge to the strategic control of whole regions. This is no less true of the radicalization in progress in Greece. And in all cases, radicalizing societies and states have been subjected to a systematic policy of destabilization by the US-led alliance. This has included economic and military sanctions, support for internal ‘pro-democracy’ and secessionist movements, coups d’état, and even outright invasion, as in the recent case of Libya. The sustained radicalization of socio-political forces in Greece is especially peculiar, not only because of the country’s semi-peripheral character, but also because it is located within the European Union, within the Eurozone, and within NATO. This puts us in uncharted waters.

Before we look more closely to the political dynamic of Greece’s radicalization, it is important to debunk some myths related to the causes of its crisis.

Demand Compression and Poverty

As expected, the economic crisis in Greece has served as an alibi for the tightening of the fiscal straightjacket, reduction in public spending, and deregulation of labor markets. There was an early euphoria about a new Keynesianism, against neoliberal orthodoxy, but this proved ephemeral and only served to legitimize generous state support and rescue of financial institutions.

The economic crisis in Greece has been presented, as in every other case, not as a global crisis, but rather as an individual country’s problem reflecting its own imbalances and profligacy. It has been presented as an isolated event, for which Greek workers and their politicians are to blame. Furthermore, according to the orthodox hypothesis of moral hazard, Greek workers have to be penalized severely, because in the years before the crisis they enjoyed a high standard of living, worked less than other Europeans, and received too much in social protection. These views, despite lacking any empirical plausibility, have dominated public debate, nationally and internationally.

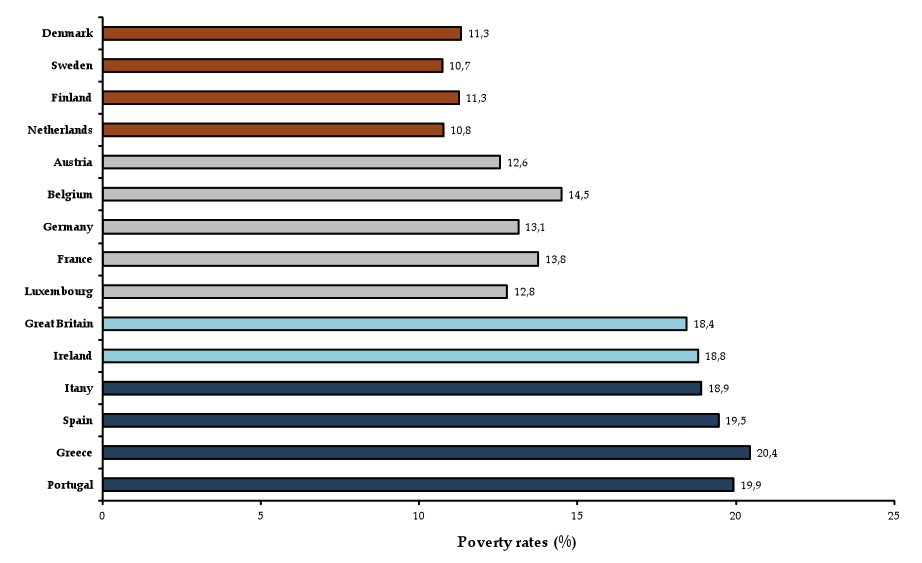

The official empirical evidence by Eurostat does not support the view of Greek profligacy. Eurostat estimates on poverty, based on the most recent data collected in 2009, before the onset of the crisis, adopt a broadly used definition of poverty, whereby the poverty line is set at 60 percent of a country’s median equivalent income. The data shows that, since the mid-1990s (for which we have comparable data for EU countries), poverty in Greece was consistently much higher than the corresponding average figures for all EU15 and EU27 countries (see epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu). As Figure 1 below shows, Greece had on average the highest poverty rate among EU15 countries during the period 1995-2010.

Figure 1: Poverty rates in the EU15, 1995-2010 (1994-2009 incomes), average values (poverty line set at 60 percent of the national median equivalent disposable income)

Source: www.ineobservatory.gr (based on Eurostat data)

However, as noted above, these estimates are based on poverty lines defined at national level. Papatheodorou and Dafermos (2010a) have shown that, when the comparison is based on a common EU-wide poverty line, the true dimension of the differences in living standards between Greece and the rest of Europe becomes clearer. Comparable estimates of poverty rates in the EU, based on the Greek poverty line, and taking into account differences in purchasing power, show that, in most EU15 countries (excepting Portugal, Italy, and Spain), less than 6 percent of the population has living standards as low as the poorest 20 percent of Greeks.

On the other hand, it has been argued that these high poverty rates exist because Greeks work less hard or fewer hours than the rest of the EU population. This is an argument that has also been widely reproduced by the media, particularly during the period in which austerity programs were introduced. But again, Eurostat data provides a totally different picture. The average hours that Greeks work per week in their main jobs are the highest among all the EU27 countries. Thus, in 2011, Greeks worked on average 42 hours weekly in their main jobs (see epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu), significantly higher than the corresponding figure for the total EU27, which is 37 hours. Compared to the other Europeans, Greeks work more hours as well as have one of the highest poverty rates in Europe.

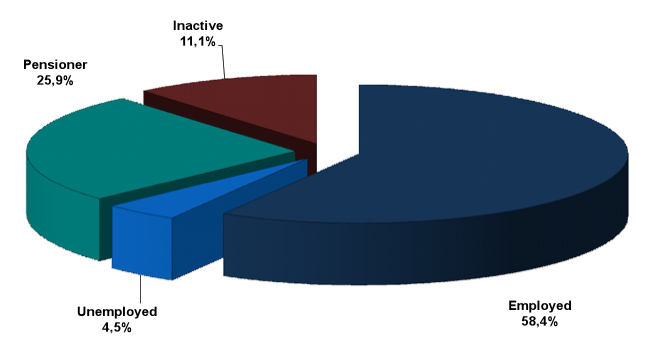

The above figures bring us to another crucial notion that emerges from the dominant discourse: the notion that poverty is associated mainly with unemployment. Thus, they claim, reducing unemployment will be the most effective measure to alleviate poverty. Considering unemployment as structural, the remedies proposed, at both country and EU levels, are those of labor market deregulation and flexibilization of labor contracts. In this argument, the association of unemployment with poverty is justified by the high risk of poverty faced by the unemployed.

Of course, no one would doubt that poverty is associated with unemployment. However, a more careful examination of the relevant data reveals that other social categories are also associated with equally high risks of poverty (see Papatheodorou and Dafermos 2010b). For example, farmers in Greece, and those working in the agricultural sector generally, show an even higher poverty risk than the unemployed. Additionally, part-time employees also face very high poverty rates. Moreover, as Figure 2 shows, more than 58 percent of those in poverty are members of households with an employed head of household. Overall, almost 85 percent of the Greek poor live in households that are headed by an employed person or a retiree. Fewer than 1 out of 20 poor live in households with a head of household unemployed. These figures reveal that poverty is not associated with only unemployment. Having a job in Greece has never guaranteed escape from poverty.

Figure 2: Contribution (%) to total poverty by the employment status of the head of household, Greece, 2008 (2007 incomes)

Figure 2: Contribution (%) to total poverty by the employment status of the head of household, Greece, 2008 (2007 incomes)

Source: Papatheodorou and Dafermos (2010b)

It should also be noted that due to austerity measures, for a large number of employees, particular the young, the minimum net monthly wage for full-time employment has now been reduced to an amount that is lower than the country’s poverty line for a single person in 2010. Of course, as mentioned earlier, the above estimates refer to a period before the current economic crisis took a significant toll on incomes. Yet, they strongly suggest that the impact of the economic crisis on poverty will not be restricted only to those who suffer directly from the huge increase in unemployment. Poverty will — probably more importantly — be affected by the austerity policies that promote the deregulation of the labor market, the abandoning of collective bargaining, the reduction of minimum wages and salaries, and the increase of the flexibility of the labor market, particularly of part-time contracts.

One would have hoped that, during the crisis, the social protection system in Greece would be reinforced, in order to protect people from the increasing risk of poverty and deprivation. Yet, social protection and corresponding social spending has itself been demonized as a contributor to the burgeoning public debt and hence the economic crisis. Claims abound that social spending has been too generous and too high relative to the country’s level of economic growth.

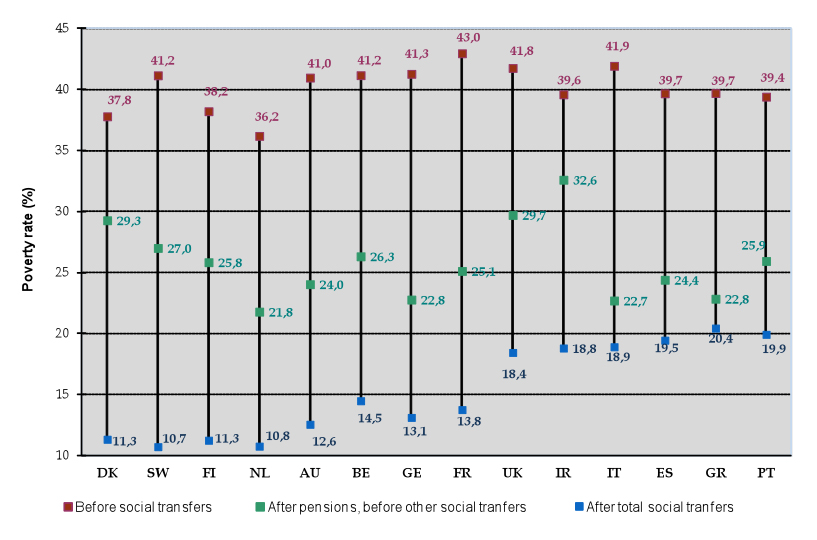

Again, the empirical data do not provide any support to these views. Social expenditures in Greece, as a percentage of GDP, have been significantly lower than the average corresponding figures for the EU. Only in very recent years has this gap between the Greek and the EU figures been narrowed. Additionally, as Figure 3 shows, the country’s social protection system is particularly weak in alleviating poverty and inequality. Social transfers (except pensions) in Greece have by far the weakest distributional impact in reducing poverty among EU countries. Thus, the high poverty rates in Greece are mainly a result of the weak distributional impact of social transfers.

Figure 3: Poverty rates (%) in the EU15 for incomes before and after social transfers, 2010 (2009 incomes) (poverty line set to 60% of the national median equivalized disposable income)

Figure 3: Poverty rates (%) in the EU15 for incomes before and after social transfers, 2010 (2009 incomes) (poverty line set to 60% of the national median equivalized disposable income)

Source: www.ineobservatory.gr (based on Eurostat’s data)

As we can see, for household income before social transfers, poverty in Greece is not one of the highest in the EU. Moreover, for income after pensions, poverty in Greece is among the lowest in the EU15. It is the other social transfers in cash, that is, the various social benefits except pensions, that have a very weak distributional impact in Greece compared to other EU countries.

The austerity program in Greece has been further undermining welfare rights and weakening the already weak Greek social protection system (see Petmesidou 2011). Thus, pension incomes (current and future) and social assistance benefits have now been significantly reduced and large cuts in social services have taken place. A new basic pension of €360 per month, funded by general taxation, is well below the country’s 2010 poverty line for a single person (€598 per month, referring to 2009 incomes). However, this amount could be further reduced if economic conditions worsen. Similarly, unemployment benefits are also well below the country’s poverty line.

It is evident that austerity and stabilization measures will increase poverty in Greece and will reduce further the incomes in that part of the population that has the highest rate of consumption (low and middle income strata), with profound implications for total demand and growth.

The Dynamics of Political Radicalization

The austerity measures and the attendant social fallout have had very significant effects both in terms of social mobilization and politics. The evolution of mass protests has corresponded to the schema characterized by Stathis Kouvelakis as “protracted popular warfare,” whereby each successive wave of austerity measures has led to a new wave of social protests, each being more intense than the one preceding it.

The first key date in the process of radicalization was 5 May 2011, when, following the announcement of the first Memorandum for austerity measures, a human sea of hundreds of thousands of people deluged all of the large cities. There followed a number of other days with strikes throughout the country, albeit without the massive participation of 5 March.

The second great wave of mobilizations occurred between 25 May 2011 and 15 July 2011, which saw the unfolding of the so-called “movement of public squares.” This was something truly unprecedented in Greek political history. On the evening of 25 May, in response to calls issued via Facebook, thousands of people occupied Syntagma Square in central Athens, directly opposite the Greek parliament. The most pessimistic observers believed that this particular mobilization was an imitation of what had happened at Tahrir Square in Egypt, or Puerta del Sol in Madrid, and would not have staying power. They were soon proved wrong: day after day, more and more people came out, and similar occupations spread to all the public squares of Greek cities and towns. The result was that the Greek people came into contact with mobilizations of an unprecedented type that took place on a daily basis: every evening people came to the squares, shouted slogans, participated in public meetings, conducted group discussions with other “indignados,” thereby initiating a process of mass re-politicization.

An important role in all this was played by the big demonstrations that were also organized at this time. The high point was the demonstration of 15 June in which between 360,000 and 600,000 people participated. In total, according to one study, in that two-month period approximately 2,600,000 people (26 percent of the Greek population) took part in at least one mobilization. But the parliamentary vote in support of the new package of austerity measures (the Medium-Term Program) promising the discounting of debt brought gradual abatement to the mobilizations.

New mass protests emerged during the two-day countrywide strike of 19-20 October 2011. On the first day, in particular, the number of demonstrators must have been higher than on 15 June. A few days later, as the Papandreou government was celebrating the approval of the Medium-Term Program by the European Union, there was a qualitative shift in the character of the popular movement. On 28 October — a National Day remembering Greek resistance to fascist occupation — significant mobilizations occurred during the military processions, some of which had to be cancelled, most importantly in the second largest city, Thessaloniki, where facing cries of condemnation the President of the Republic himself, Karolos Papoulias, was obliged to withdraw. In our opinion, this alone was a breakthrough for the political consciousness of Greek working people. On the very day that the Greek bourgeois state sought legitimation through traditional commemorations, the Greek people called it into question! This amounted to direct rejection of the terms of the hegemony of the dominant bloc, indicating with stark clarity how expressions of social discontent were acquiring ever greater resonance.

The decision by the two largest parties to vote for a second Memorandum, which contained even more anti-popular measures, triggered new mobilizations in February 2012. These culminated in the demonstrations of 12 February, when the total number of participants nationally must have been, by conservative estimates, greater than at any time since 1974, the year which marked the transition to democracy.

At the political level, these social reactions have had very powerful repercussions. In terms of the strength of the traditional parliamentary groups, there have been, within the space of two and a half years, significant changes in their composition. Around 30 parliamentarians who disagreed with the policies of imposing austerity measures abandoned the traditional social-democratic party, PASOK, which had won the majority of seats in the 2009 elections, and 10 resigned. Also, around 15 abandoned the conservative New Democracy party for the same reasons. There have also been losses due to disagreements within the ultra-conservative LAOS party, which for an extended period had consented to the austerity measures. Overall, more than 60 parliamentarians elected in 2009 no longer belonged to the party through which they were elected.

In electoral terms, the influence of the three parties that supported these policies plummeted: the electoral constituency that had voted for these parties before the crisis, amounting to 80 percent, was now reduced to 40 percent. This development is particularly important if we consider that, since 1981, the two traditional parties that had alternated in power, PASOK and New Democracy, had consistently received between 75 and 87 percent of the vote. It is clear that implementation of the austerity measures has fractured long-term relations of political representation. Particularly after the new measures of the mid-2011, the mood of hostility towards the ministers and parliamentarians who supported them intensified considerably. It would be no exaggeration to say that they would no longer dare to show their faces in public, for fear of the censure they would encounter from ordinary citizens.

The post-1974 system of political representation was dealt a final blow in the 6 May 2012 parliamentary elections when PASOK and New Democracy took a decisive beating, together mustering no more than 33 percent of the popular vote. On this day, parliamentary representation fragmented among seven political parties: New Democracy placed first, with 19 percent of the popular vote, having lost at least 10 percent of its vote to a newly-formed right-wing splinter party, the Independent Greeks, with an anti-Memorandum agenda; PASOK was routed even more severely, coming in third, with 13 percent; SYRIZA, a rising player on the left with a militant social-democratic, pro-European agenda, placed second, with 17 percent; the Communist Party, with a radical anti-capitalist, anti-EU, anti-NATO platform, stagnated at around 8 percent; and ominously, an obscure fascist party, Golden Dawn, entered parliament for the first time, with 7 percent of the vote.

A new election is now planned for 17 June, and the reshuffling of the cards is already underway. Tactical and strategic maneuvers by all parties are now revealing more clearly the unique challenges of Greece’s crisis and the severity of the trap in which the country has been caught. The range of evolving positions include inter alia: to remain in the Eurozone and the EU and renegotiate the Memorandum, as espoused by New Democracy and PASOK; to remain in the Eurozone and the EU, but default unilaterally on debt and reject the Memorandum, as espoused by SYRIZA; to reject the debt, the whole EU project, and the NATO with it, as espoused by the Communist Party.

The first position is, in effect, a policy of persisting with wage cuts down to “competitive levels,” under German economic and US military hegemony. The second position, although contradictory in essence, is accompanied with a strategy (or desire) to inspire a Europe-wide uprising, which in turn would sustain Greece’s own. A return to social-democracy is envisioned, which would put banks under state control and invest in growth, although obvious questions remain about the ways and means of Greece’s and the EU’s re-insertion in the world economic and security system. The third position, of delinking, might appear to be the most coherent, but in this case obvious questions remain about “the day after” — for in the last thirty years Greece has not cultivated any other economic or security alliances.

Whatever the actual result of the new elections might be in June, there is a diminishing chance of the Eurozone surviving, much less a chance for Europe and the world economy to embark on a new era of accumulation on the terms of a globalised law of value. The world economy that monopoly-finance capital has stitched together is indeed hanging by a thread. Having laid waste to the peripheries and semi-peripheries of the South and the East, it is now the turn of the Southern European semi-periphery. Very soon, the center will have to look into the mirror.

References

Amin, Samir (2003). Obsolescent Capitalism. London and New York, NY: Zed Books.

Arrighi, Giovanni (1997). A Ilusão do Desenvolvimento. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes.

Foster, John Bellamy (2010). “The Age of Monopoly-Finance Capital,” Monthly Review, 61(9): 1-13.

Foster, John Bellamy, Robert W. McChesney and R. Jamil Jonna (2011). “The Global Reserve Army of Labor and the New Imperialism,” Monthly Review, 63(6): 1-31.

Lapavitsas, Costas et al. (2010). Eurozone Crisis: Beggar Thyself and Thy Neighbour, RMF Occasional Report, March, www.researchonmoneyandfinance.org, accessed on 20 May 2012.

Marini, Ruy Mauro (1992). América Latina: Dependência e Integração. São Paulo: Editora Página Aberta.

Martins, Carlos Eduardo (2011). Globalização, Dependência e Neoliberalismo na América Latina. São Paulo: Editora Boitempo.

Minqi Li (2008). The Rise of China and the Demise of the Capitalist World-Economy. London: Pluto Press.

Moyo, Sam and Paris Yeros (2011). “The Fall and Rise of the National Question,” in S. Moyo and P. Yeros (eds), Reclaiming the Nation: The Return of the National Question in Africa, Asia and Latin America. London & New York, NY: Pluto Press.

Papatheodorou, Christos and Dafermos, Yannis (2010a). Structure and Trends of Economic Inequality and Poverty in Greece and EU, 1995–2008, Report 2, Observatory of Economic and SocialDevelopments, Labor Institute (in Greek). Athens: Greek General Confederation of Labor.

Papatheodorou, Christos and Dafermos, Yannis (2010b). Dimensions of Poverty and Deprivation of the Workers in Greece and Attica (in Greek). Athens: Hellenic Social Policy Association.

Petmesidou, Maria (2011). “Is the EU-IMF “Rescue Plan” Dealing a Blow to the Greek Welfare State?” CROP Poverty Brief 4, www.crop.org/viewfile.aspx?id=225, accessed on 19 May 2012.

Christos Papatheodorou is Associate Professor of Social Policy at Democritus University of Thrace, Greece; Spyros Sakellaropoulos is Assistant Professor of Social Policy at Panteion University, Greece; Paris Yeros is Adjunct Professor of International Relations at the Catholic University of Minas Gerais, Brazil. A Spanish version of this article is being published by Batalla de Ideas in Buenos Aires.