The Class Structure of Society in the Republic of Cyprus

The Class Structure of Society in the Republic of Cyprus

Abstract

This article examines the structure of contemporary society of the Republic of Cyprus in the theoretical context of the Marxist model. The decisive role in determining social stratification at the theoretical level is assigned to the concepts of exploitation and domination. The problematic of the article is opposed to notions supporting an over-inflated new bourgeois order, shaping of social classes at the global level, fracturing of exclusive correspondence between social position and class. A critical presentation is also offered of older studies on the composition of Cypriot society. This engagement with the facts leads in itself to the conclusion that Cypriot society includes a significantly broad petit bourgeoisie (around half of the population), placing Cyprus in the category of a type of ‘transitional’ society with numerically large petit bourgeois layers along side an arithmetically smaller working class[AO1] .

Keywords: Cyprus, social classes, social stratification, Marxism

- Introduction

The purpose of this article is to examine the social stratification of the Republic of Cyprus in the most recent period. In order to make this task feasible, the examination is preceded by theoretical positioning, situated within the Marxist analytical model, on the subject of social classes. The concepts of exploitation and domination are posited as the key factors in the formation of social classes. It is argued that apart from the two main classes (bourgeoisie and working class) there are other classes and strata whose sizes vary in accordance with the historical evolution of each social formation. There follows a critique of three major theorists in the neo-Marxist current (Nikos Poulantzas, Erik Olin Wright, William Robinson), aspects of whose work (disproportionate weight of the petit bourgeois strata, assignment of each position in society to a single social class, formation of transnational social classes) could serve to justify mistaken interpretations of the stratification of Cypriot society (and not only of Cyprus).

After outlining our own theoretical position, we embark on a presentation and critique of two older studies of Cypriot society, those of Demetrios Christodoulou [AO2] and of AKEL. Then empirical data from Cyprus’s statistical services is presented as being part of the theoretical framework adopted by the current study. The presentation interprets Cyprus society’s specific character and structure and compares this specific social stratification with that of other countries of the developed West.

2. Our theoretical framework

Within the framework of an article focused on the morphology of Cypriot society. it is not possible to refer extensively to theoretical issues of social class theory, which we have analyzed in detail in other work (Sakellaropoulos, 2014). For this reason we will simply mention certain aspects of our theoretical findings, choosing not to embark on more exhaustive discussion, whether inside or outside the Marxist schema.[1]

In our opinion, Lenin's definition is as pertinent as ever in clarifying the multifaceted problem of defining social classes: ‘Classes are large groups of people which differ from each other by the place they occupy in a historically determined system of social production, by their relation (in most cases fixed and formulated in law) to the means of production, by their role in the social organization of labour, and, consequently, by the mode of acquisition and the dimension of the share of social wealth of which they dispose’ (Lenin, 1977, p. 13). We might note that in Lenin’s definition there is a co-articulation of three criteria: a) position in relation to the means of production, b) position in the social division of labour, c) means of acquisition of – and level of – income (Bensaid, 1995, p. 203).

The common denominator traversing these three criteria in Lenin’s definition is the phenomenon of exploitation. The possessor of the means of production exploits the person who possesses only labour power, because the possessor pays the labourer less than the value of the work. However, in order for this social relation, derived from the possession of capital, to be reproduced (after all, this is why Marx claimed that capital is primarily a social relation), some structural characteristics must be shaped in the production process that will facilitate circulation of capital and create the hierarchical structures necessary for working discipline to become attainable.

Therefore, what is elaborated is an internally intricate but also externally pyramidal organization of production wherein, for the relations of exploitation to be implemented, relations of domination are also absolutely essential. In this sense, exploitation and, secondly, relations of domination, especially the way they are articulated into a social structure (Croix, 1984, p. 94), are the agents in formation and reproduction of social classes.

The conclusion is that the foundations of prevailing social arrangements are to be situated in the existence of relations of exploitation and domination, yet membership in a particular class depends firstly on who owns the means of production and secondly on each person’s position in the division of labour and the amount of social wealth a person extracts.

Nevertheless, it must be made clear that the economic element (relation to the means of production, level of income, etc.) is the most important and decisive, albeit not the only, element. The ‘position occupied by individuals’ may be determined by reference to both the political and the ideological elements that contribute to shaping the relations of domination. Thus the top echelon of the state bureaucracy: members of government, high-ranking military personnel, etc., belong, by virtue of their position in the machinery of power, to the bourgeois class.

The intervention of capital and the state in maintaining and reproducing relations of exploitation is continuous and embraces all levels of social activity. The reason for this is that capital does not only exploit workers economically but also exercises power over their functioning in the workplace, from the moment that it determines what and how they will produce. At the same time, through the Ideological Apparatus of the State,[2] it integrates them ideologically as the workers accept the terms of their political and economic exploitation as the ‘natural’ result of the exchange of ‘wage’ and ‘labour power’ equivalents. To put it differently, the framework of the relations of exploitation is reproduced by the political and ideological mechanisms functioning, within which capitalist power is also reproduced, not through the realization of surplus value but through reproduction of managerial and executive labour.

It should be stressed that classification of the various agents in social relations is no static, cerebral process. On the contrary, social classes are defined through an antagonistic relation: the class struggle (Balibar, 1985, p. 174), which determines the movement of history. This means that class struggle results in transformations in the positions of social categories and social strata in such a way that there is no one-to-one correspondence between assigned social class and membership in a particular professional category. Nothing is exempt from change (Aronowitz, 2002, p. 56).

With these general definitions as our starting point, we proceed to make some conclusions about the most significant characteristics of the bourgeois class: it is the class that directs the capitalist productive process, and it always, with a view to its own interests, defines the context and the hierarchies of the social praxis dominated by capital (Bihr, 1989, p. 88-89). Its position is based on owning the means of production and subjecting society to its power. At a level of high abstraction, its members are defined as non-productive exploiters/possessors/extractors of surplus labour-cum-organisers of the mechanisms of domination (Johnson, 1977, p. 203).

The working class is deprived of possessing the means of production, but it performs all those practices that are aimed at furthering reproduction of capital and reinforcing social power. It neither possesses control of, nor is able to influence the context of its labour. It simply plays an executive role within the social division of labour (Bihr, 1989, p. 90). In a more abstract away we could define the working class as consisting of exploited/non-possessors/producers/wage-earners enduring the constraints imposed by the mechanism of domination (Johnson, 1977, pp. 202-203).

Nevertheless, the existence of the two basic classes of the capitalist mode of production does not mean that there are not other social classes in a society. Only at a high level of abstraction – that of the mode of production – is it possible to speak of only two classes. At the national social formations level, the number of classes is greater precisely because the different historical development of each formation includes more modes of production but also ‘a) because there are also more modes of production, that is to say forms of organization of the productive process, which are not based on the appropriation of surplus labour, on exploitation, and b) because some of the class functions of the dominant class are normally delegated to social groups that are not part of the dominant class (are not owners of the means of production)’ (Milios, 2002, p. 64). Τhis social class we name the petit bourgeoisie occupies, in the active sense of the term, a position between the working class and the bourgeoisie.

Τhe basic characteristic of members of the petit bourgeoisie is that their income is greater than what is necessary for reproduction of their labour power, irrespective of how this is achieved. Sometimes it is realized through the appropriation of surplus value and sometimes through earnings that exceed the cost of reproduction of their labour power. Above and beyond that a second characteristic is that they are not exclusively subjected to domination by other classes. The traditional petit bourgeoisie exerts power over the workers it employs; the new salaried petit bourgeoisie is subject to the power of capital but also exerts power over the working class, whereas the self-employed (who are also to be included in the new petit bourgeoisie) neither exert power nor are subjected to it.

Further refining this line of thought we could argue that the petit bourgeoisie is divisible into the traditional petit bourgeoisie and the new petit bourgeoisie. The traditional petit bourgeoisie includes owners of small manufacturing companies, small family businesses and small commercial enterprises not involved with extended reproduction of capital (that is to say employing up to nine workers).[3] The new petit bourgeoisie is comprised of all those who work as either self-employed professionals or salaried employees engaged in supervising and organizing the work system, realizing surplus value, overseeing the cohesiveness of capitalist operations or, finally, legitimizing the terms of reproduction of existing social relations.

Nevertheless, if the theoretical approach of social stratification is to be comprehensive, it is necessary to refer to cross-class social categories, such as farmers, civil servants and intellectuals, besides the basic class divisions and the petit bourgeoisie.

Farmers fall into the above category, because despite being involved in land cultivation, they differ from each other depending on the expanse of the land they cultivate and the extent to which they employ land laborers

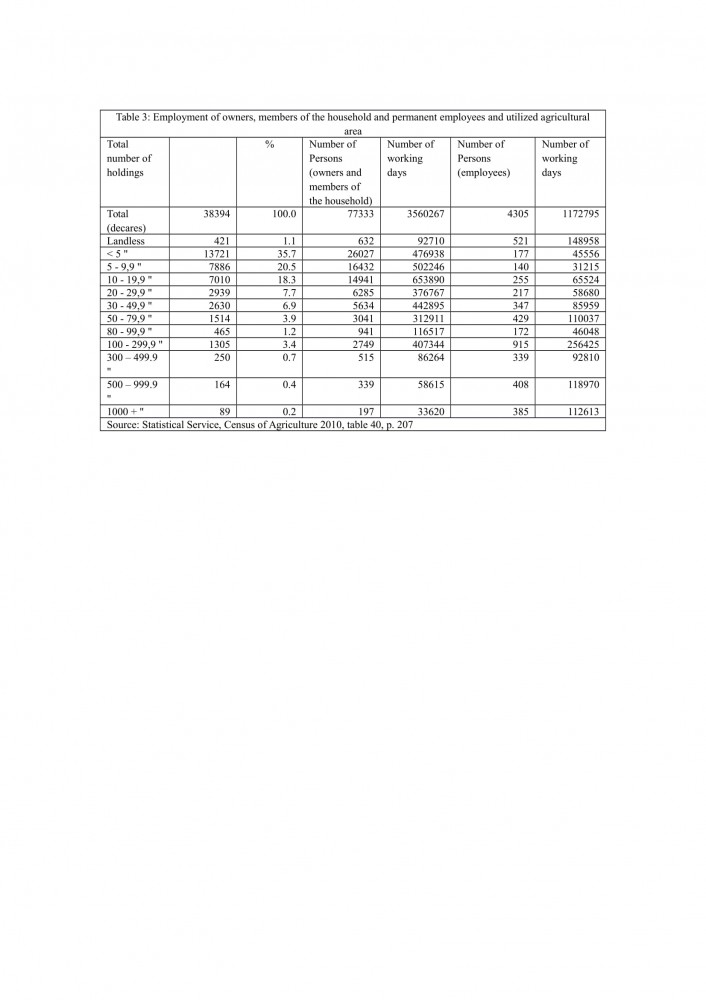

In Cyprus, the agricultural strata and small landowners of up to 30 decares are the less affluent layers of rural society and do not employ wage labour. Correspondingly, proprietors who make limited use of wage labour to cultivate their land, because they own between 30 and 99 decares and are engaged in simple reproduction of their capital, belong to the intermediate rural strata; whereas, those who employ a wide range of salaried employees, and are proprietors of more than 100 decares, enabling them to proceed with extended reproduction of capital, belong to the wealthy rural strata.

Another stratum that is distinctive for its cross-class characteristics is that of the civil servants, because a civil servant may be employed in very different sectors. A significant sector employed in public enterprises such as processing, energy and water supply, communications, transport and banks, are productive working people (Meiksins, 1986, p. 17), because they are paid less than the value of their work when they exchange their labour power for capital. In that sense individuals in this category are both productive workers and people exploited by the collective capitalist and to be included in the working class.

On the other hand people working in education, in cases where education is provided free, and administrative personnel in the various public bodies and ministries are not productive workers but, with the exception of senior and middle-ranking officials in the ministries, the armed forces, university professors and civil servants who are members of the new petit bourgeoisie (engineers, lawyers, doctors) and work in the public sector, belong to the working class for the following reasons:

1) They do not own their means of production.

2) Their surplus labour is subject to extraction.

3) They perform the function of the collective worker (Carchedi, 1977, p. 134).

4) They are remunerated with a salary which is determined by state income policy (Lytras, 1993, p. 98), which is equal to the value of their labour power, because it correlates directly with salaries in the private sector (Bouvier-Ajam and Mury, 1963, p. 73) which tend not to rise above the level of reproducing their labour power.

Therefore, civil servants as a collectivity, united essentially by the institution of tenure, are a cross-class entity. The great majority can be classified as working class; the middle-ranking officials in the ministries, public enterprises and the military, and university teachers belong to the petit bourgeoisie, and the heads of administration (political, military, academic) and the managers of state-owned companies belong to the bourgeoisie by virtue of the dominant position they occupy within the collective capitalist known as the State.

Another category of individuals not belonging to a specific social class are the intellectuals. This is not a professional category but a social layer, a large number of which are salary earners. Gramsci, who considered the question in depth, regarded the action of intellectuals as confined to the realm of the superstructure and pertaining to both the ‘private sphere’ and ‘political society’. Those who are in the private sphere are concerned primarily with the functioning of their hegemony, and in the latter are concerned with the management of their direct domination (Gramsci, 1972, p. 62). There is an internal graduation to their activity. The highest rung is occupied by individuals who have undertaken the formulation, organization and systematization of the dominant ideology (Gramsci, 1972, p. 63) and who belong to the bourgeoisie. The lower levels include executive officers whose concern is the generation and promotion of consent and discipline and who are to be included in the petit bourgeoisie.

Workers who contribute intellectual labour constitute a separate category. They produce surplus labour/value for their employers (e.g., educators in the private sector). These ‘intellectual workers’, from whom surplus labour/value is extracted, belong to the working class. They do not count as ‘intellectuals’ because they are charged not with planning and organizing consent but rather with implementing the terms of its realization.

3.The Debate in the Framework of the Neo-Marxist School

What was said in the previous paragraph had to do with the emergence of our theoretical approach to social classes. On the basis of this problematic we engage with three of the most prominent theoreticians of the social classes in the so-called neo-Marxist school, namely Nikos Poulantzas, Erik Olin Wright and William Robinson. We do this because each of them (Poulantzas for the new bourgeoisie, Robinson for the globalization of social classes, Wright for the contradictory character of class situatedness) has developed an approach that has influenced the discussion by opening up issues that should be a subject for debate for the sake of further clarification of the theoretical framework adopted by our side.

a) Nikos Poulantzas

Nikos Poulantzas judges that the heart of the capitalist system is the production of surplus value, so that this form of production is the decisive factor for dividing society into classes and he upholds the view that the working class is defined ‘by productive labour, which under capitalism means labour that directly produces surplus-value’ (Poulantzas, 1979, p. 94). As a result, Poulantzas claims that only workers in the industrial sector who are immediate producers of surplus value belong to the working class. Those who do not possess the means of production are included in the new petit-bourgeoisie.

.

Poulantzas's position suffers from two weaknesses in this respect. The first is reductionism whereby the working class as a whole is identified with productive workers and excluded from the category of non-productive workers. ‘The working class’ thus appears as a concept derived from the concept of productive labour. By contrast, Resnick and Wolff observe it would be more appropriate to define the working class as a particular social group acting within a capitalist social formation (Resnick and Wolff, 1982, p. 9), which implies the need to analyze the particular social conditions that led to its formation without finding it necessary to import ancillary concepts. His second error is to conceive of the aim of production under capitalism as the creation of capitalist commodities, the value of which is expressed partly in the surplus value produced. The question is not one of producing commodities but of realizing surplus value, or profit (Nagels, 1974, p. 131), through a uniform capitalist process (Berthoud, 1974, p. 102). If the products do not reach the market and are not sold, neither will profit be realized nor will self-reproduction of capital take place, as the merchant-capitalist will not again order commodities from the manufacturer-capitalist.

Perhaps our most significant disagreement with Poulantzas has to do with his use of the term ‘services’. It is one thing for the term ‘service’ to denote a form of exchange of the product with money, and quite another for it to mean a form of production of immaterial products (Colliot-Thélène, 1975, p. 97). Poulantzas seems to make the mistake of defining productive labour through its material content, as a result of the transformation of nature, whereas Marx focuses on the social form of labour, particularly on the relations of production, on the basis of which the productive process is put into operation (Bihr, 1989, pp. 47-48). Whether the form of the product is ‘material’ or ‘immaterial’ is irrelevant, but it should be transformed into a commodity and exchanged with the general equivalent (money) and that surplus value should be realized.

Finally, while Poulantzas clearly adheres to the Marxist analytical model, he appears to neglect the fundamental element of Marxian theory that is class struggle, along with its effects on transformations in social stratification. This makes his approach to the enlargement of the tertiary sector awkward, a phenomenon which exposes further the commercialization of many more aspects of everyday life in which a significant faction of the working class participate fully. (Αronowitz, 2002, p. 59). Correspondingly, changes in the technical division of labour result in older specialists losing intellectual autonomy and progressive dissipation of their distinctive qualities (Martin, 2015, pp. 259-260).[4]

b) Erik Olin Wright

Erik Olin Wright’s view of social stratification also warrants inclusion in the so-called radical approaches. His approach is clearly influenced by the positions of analytical Marxism, and especially by Roemer, according to whom exploitation is a parameter in a negotiating relationship between individuals in the market. To be precise, the basic position compares different systems of exploitation and treats productive organization as a ‘game’ whose players enjoy different forms of ownership (e.g. resources such as specialized skills or financial capital) through which they enter production, utilizing them to generate income on the basis of a specific framework of rules (Wright, 1987, p. 68).

On the basis of the above, for Wright the view that each position within a class structure corresponds to a single social class is to be rejected. There are positions which, due to their complex class character, pertain to more than one social class. This leads him to the conclusion that it is appropriate to speak of contradictory class positions. Such contradictory class positions are to be found in three ‘regions’ of the capitalist social stratification where entities that are part of different social classes exhibit common structural elements.

The first region is that generated between the new salaried petit bourgeoisie and the working class. The individuals concerned are neither workers nor lower middle class. The second region occupies a position between a traditional bourgeois class and a bourgeoisie including elements not belonging to either of the aforementioned. They are small entrepreneurs with relatively little capital and few employees. The third region is situated between wage earners and capitalists, and the players in it are the so-called middle strata who are wage-earners but have skills and/or exercise power (Wright, 1976, p. 39, 1997, pp. 19-23). The upshot is Wright’s conclusion that in modern capitalist societies there are 12 classes (Wright, 1987, p. 88) based on a combination of criteria: a) possession/non-possession of means of production, b) administrative proficiency, c) vocational specialization and credentials.

Of course, such a position raises a number of questions. Particularly problematic is the position on the skills possessed by certain agencies with which they can exploit the working class, resulting in the creation of a complex structure with 12 classes, where the working class comprises the lowest rung in the hierarchy. Only unskilled labourers belong to this class, because those possessing any specialized qualification are immediately elevated to a higher social rank. Similarly, membership of the bourgeoisie is confined to big capitalists who own the means of production (Malakos, 1991, pp. 71-72). The petit bourgeoisie are exclusively self-employed. Small capital holders with few employees are in the contradictory class position of small employers and are not to be included in the traditional petit bourgeoisie.

Besides that, precisely because much of the weight of the analysis of exploitation as a phenomenon is regarding qualifications and credentials, Wright ultimately tends to portray the phenomenon as exploitation of one person by another (Meiksins 1986: 109). The reason for this is that exploitation for Wright is not only economic in content, but it becomes more likely when there is inequality in possession of specialties or unequal possibilities for exercising authority (Carter, 1986, p. 687). It is here that Wright’s and, more generally, analytical Marxism’s basic methodological problem emerges. The class struggle that shapes social classes is a struggle for social power and the correlation of power is what, at every point, shapes the rules of its conduct (Bensaid, 1995, p. 99).

c) William Robinson

Employing Marxian methodology, William Robinson comprehensively and clearly expounds the theory of the Transnational Bourgeois Class (TBC). For him the TBS was generated when the capitalist system entered into the historical era of globalization. The question that Robinson poses is how is it possible for capitalism at an ever accelerating rate to become transnational (as labour does) and for the same thing not to happen with capitalists and workers (Robinson, 2001-2002, p. 501). His answer is that only when we understand the meaning and the dynamic of globalized capitalism and the consequences it entails at every level of human practice will we be able to comprehend what is happening in terms of social stratification theory. The nature of globalized capitalism is such that the local, the regional and the global are no longer mediated through nation states and national productive systems. The classes and the social groups encounter each other at these multiple levels in new ways that render them increasingly less connected with old national/state identities and mediations.

This means that, in this new period, factions of the bourgeois classes from different countries are being merged with new capitalist groupings in transnational space (Robinson, 2012, p. 355). This new transnational bourgeoisie is the faction of the global bourgeoisie, represented by transnational capital (Robinson, 2001, p. 165). It has a consciousness of its own identity and at its summit is a managerial elite that controls the processes of globalized political strategy, corresponding to the transnational financial capital that is the hegemonic faction of capital globally. (Burbach and Robinson, 1999, pp. 33-34). The transnational bourgeoisie is to be distinguished from the national and local capitalists through its having been implicated in globalized production and through management of the globalized circulation of accumulation, something that endows it with an objective class foundation and identity that situates it in the globalized system irrespective of its geographical origin. As regards action, given the consciousness of its transnational character, the transnational bourgeoisie promotes a class-based project of capitalist globalization reflecting the globalized character of its decisions and the rise of a transnational state machine subject to its directives (Robinson and Harris, 2000, p. 22).

From the moment that the national productive structures are transformed into transnational ones, the global classes, whose organic development took place within the nation state, are also transformed through incorporation into the ‘national’ classes of other countries. The formation of the global social class accelerates dividing the world into a global bourgeoisie and a global proletariat. (Robinson and Harris, 2000, p. 17; Robinson, 2001, p. 168-169).[5]

The “”into transnational ones” must be unchanged

Our position, in contrast to that of Robinson, is that one cannot speak of either a global bourgeoisie or of a global proletariat. The absence of a single economic structure creates different conditions of profitability, and on the basis of this factor the national classes have been impelled into action, particularly in the wake of the crisis of overaccumulation (1973), which initiated a significant downward trend in profitability. The most powerful of the national bourgeoisies, i.e. those with higher levels of productivity, are attempting to expand their activities abroad – but only where they feel they can achieve a high level of profitability.

From the moment that the dynamic section of a bourgeoisie succeeds in penetrating other social formations, it assumes the character of the national bourgeoisie of the national formation in question. Thus, there is no SBO consisting of capitalists with shared supranational characteristics. The considerations that are of primary interest to each capitalist are the percentage of profit to be extracted from the employees, the level of the collective worker and the average rate of profit prevailing in the national economy in question.

By the same token there is no supranational proletariat with common supranational interests. Members of the working class live under different conditions of exploitation from one formation to another, and their social struggles modify the specific national framework of exploitation. On a second plane, in the context of the imperialist chain, the national capitals within which the results of class struggle have been registered, all compete with each other.

The two previous sections presented the main position supported in this article on the theory of social classes and its differences with three of the most important views developed within the neo-Marxist theoretical current. A specific choice was made to answer questions relating to general considerations concerning the theory of social classes on the creation of worldwide classes, the petit bourgeoisification of contemporary societies, and the downgrading of the significance of the bourgeoisie/working class dichotomy.

In continuation, and prior to presentation of data for assessment of the social structure, it may be appropriate that there be some mention of the two previous studies (Christodoulou, 1995 and AKEL, 1996) that have been conducted on social stratification in Cyprus. The decision was that this should be done after presentation of our basic theoretical positions so as to highlight the methodological differences that distinguish this study from its two predecessors.

5.The Studies by Demetrios Christodoulou (1995) and AKEL (1996)

Christodoulou’s study focuses primarily on the uneven pattern of distribution of economic growth in the Republic of Cyprus following the invasion. Thus, as regards the overall level of social inequality on the basis of 1991 data, 3% of households lived in absolute poverty and 4.3% in relative poverty. Above and beyond that, the gross annual income per family in 1991 came to CYP 10,975. But 11% of households had an income of less than CYP 2,500 pounds (i.e. 25% of the average income) and 3% had an income of over CYP 30,000 pounds. Ten percent of the total number of households had an income that barely came to 1.57% of the total income, while the wealthiest 10% of households had a share of the income corresponding to 26.3% of the total. This means that the most affluent 10% enjoyed 26.3% ÷ 1.57% = 16.75 times more income than the poorest 10% (Christodoulou, 1995, p. 48).

As for the social structuring of the Cypriot population, Christodoulou concludes that the wealthiest layers comprise 5%, a broad middle class represents 65% and a working class embraces 30% of the population (Christodoulou, 1995, pp. 47-48). It is however by no means obvious what methodology he employed to arrive at these conclusions. We might point out that the lack of clarity is even more pronounced if we take into account that, before presenting these estimates, he submits, once again without any preceding presentation of the calculations, a more complicated breakdown of the social structure (rural proletariat 1%, rural lower middle class and middle class 25%, manual working class 30%, white-collar working class 20%, proprietors of non-farming small businesses, privileged employers 10%). No figures are mentioned for the managerial class and the owners of some larger and some medium-sized businesses, but they are characterized as a ‘small and powerful class’, nor for independent working professionals, but they are described as a ‘small high-income class’. Once again, it is not at all obvious by what means we have been led to this conclusion.

The AKEL study includes a lengthy section on socio-economic development in Cyprus, a theoretical part on the concepts of class stratification and finally a part which includes the statistical data to map the social structure of Cyprus. It concludes that, in 1992, 60.7% of the economically active population belonged to the working class; the middle strata of the urban population fluctuated between 14.7% and 16.4% of the economically active population; the middle strata of the rural population was 9.8%; the bourgeoisie accounted for between 4.7% and 6.5% of the economically active population and the upper-bourgeoisie of Cyprus is estimated at around 1% of the population (AKEL, 1996, pp. 94–100).

The AKEL study is undoubtedly a comprehensive effort which, on the basis of a specific methodology, ends up with an overview of Cypriot society in the early 1990s. In our study, apart from the fact that it refers to the same community, but about 20 years after Cyprus had joined the European Union[AO3] , there are a number of methodological differences from the AKEL study.

For a start, the Cyprus Communist Party’s (AKEL’s) study is timid about referring to researchers beyond the classics of Marxism-Leninism. This is not simply because an absence of quotations from later Marxist-oriented analysts but also it is an indirect acceptance that from Lenin’s time to the present day there have not been any noteworthy changes. Thus developments such as strengthening the role of managers in monopolized enterprises, societies’ urbanization, salaried staff assuming executive functions, the new petit bourgeoisie playing key tactical roles, agricultural production changing due to food companies pre-purchasing produce are downplayed in the context of AKEL’s analysis. For our part, bearing in mind the significance of the central point of Lenin’s intervention on the question of stratification in a capitalist society, we attempt to enrich it through using additional tools corresponding to present-day developments (integration of managers into the bourgeoisie, the existence and segregation of two distinct sectors of the petit bourgeois, differences of social insertion within the farming strata of the population, see below).

To put it differently, our view is that, in the present day, using the term ‘middle class’ and differentiating based on geographical criteria, which may have been of some value in the transition period to monopoly capitalism as described by Lenin, obfuscates analysis rather than facilitates it.

In this sense we believe that is correct to characterize the petit bourgeois class as an intermediary class, subordinated to the two fundamental classes (Resnick and Wolff, 1986, p. 102) and not to equate it with the middle class. Synonymous as these two terms may seem, in this case their referents are completely different. The use of term ‘middle class’ in AKEL’s research implies an imaginary continuity in social stratification, a graded pyramid at the basis of which is the working class, in the middle the so-called middle strata and on the top the ruling class. By contrast, the term ‘intermediary’ denotes an intermediate social class, which is not economically exploited but functions in an ancillary capacity within the structures of economic exploitation.

Similarly, breaking down the urban social classes fragments the uniformity of the capitalist mode of production on the basis of ‘spatiality’, highlighting two problems: one is that the countryside also has factories, shops, services, etc., and even agricultural production has been unequivocally incorporated into the capitalist productive framework. This is accomplished by the capitalist system adopting a plethora of specialized measures: 1) politically motivated reductions in the price of agricultural products and increases in the prices of industrial products, 2) high rates of taxation that are particularly burdensome for farm producers, 3) inflationary policies which, as forms of compulsory saving, serve to redistribute wealth to the advantage of the wealthiest (Vergopoulos, 1974, pp. 172 ff), 4) agreement between oligopolistic capital and family farms for production of a specific quantity (on a ‘piecework’ basis) for big food and animal product companies.

The AKEL study employs certain, newly coined terms such as intellectuals joining the working class (p. 92) and ambiguous class status (p.91), and the equation of ‘intellectuals’ with graduates of university and higher education is also questionable (pp. 94-95).

6.Application of the Theoretical Model to Cypriot Society

The next step will be to implement the adopted theoretical approach to highlight the morphology of Cypriot society. Empirical material is used multidimensionally so as to meet the requirements of the theoretical model. The study is accordingly not limited to registration of economic categories (e.g. presentation of the 10% most affluent households, their designation as bourgeois, with 60% assigned to the middle class and 30% to the working class). Instead, it takes a variety of data (position and occupation at work, record of number of enterprises, record of agricultural crops) and performs calculations based on theoretical parameters related to ownership of the means of production, role in the social division of labour, specific position in accordance with size of the business and area under cultivation, stratification within the social layer of civil servants. Following this, there should be two assumptions. The first is that if there were more detailed data for some categories (e.g. civil servants’ professions and positions at work and/or detailed data on the distribution of positions inside private companies), more accurate conclusions could be drawn. The second is that whatever result emerges, it will be nothing more than a general picture of Cypriot society. A number of practices such as the shadow economy and/or illegal activities that also have economic impact are not easy to calculate, thus obliging the researcher to accept a less accurate picture than would be desirable.

7.Presentation of the Empirical Data

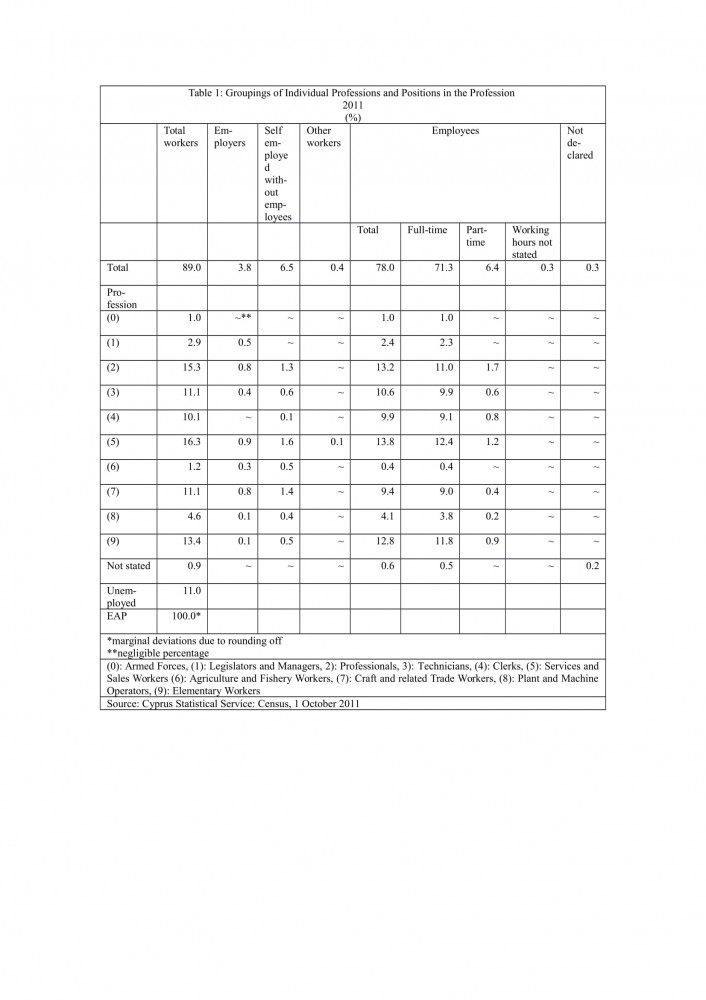

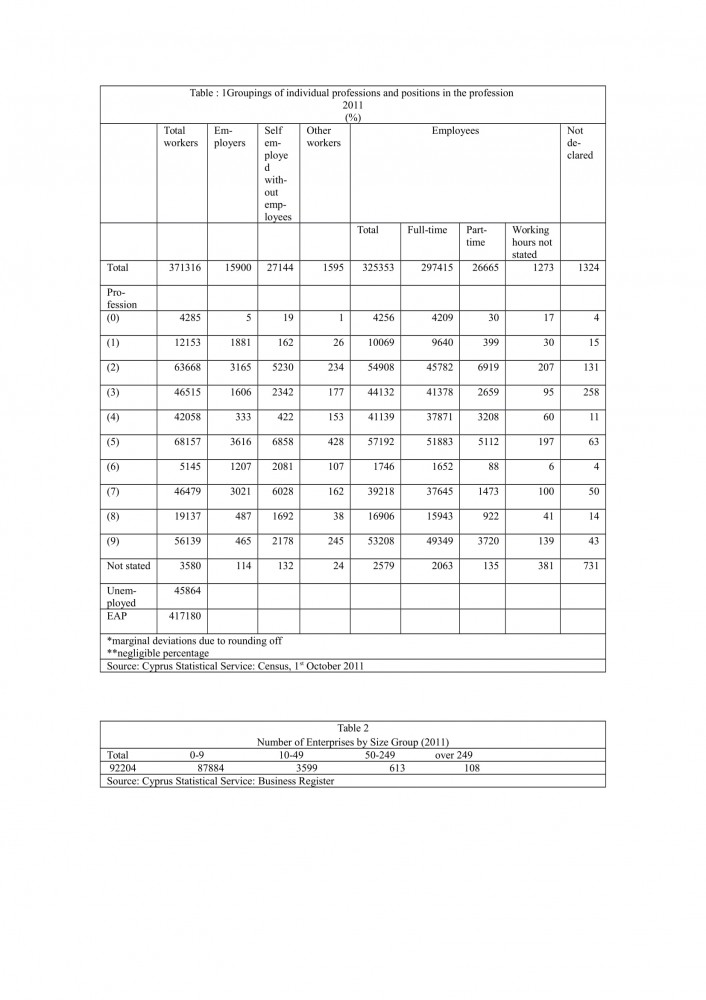

Within the parameters of the outlined methodological framework, we can proceed to analyse the Cypriot social classes in 2011. We propose to utilize data from the 2011 census on the mode of employment of the workforce (occupation and position in the workplace) in addition to the methodology adopted in another study (Sakellaropoulos, 2014) which we cannot present in detail here. The final result for 2011 can be seen in this table, based on elaboration of the relevant data from Table 1 in the Appendix.

To arrive at an approximate figure for the size of the bourgeois class, we postulate that the 4,500 employers (or 1.0% of the potential workforce[6]), who own businesses employing more than nine wage-earners[7] and pursue expanded reproduction of capital belong to the bourgeois class. Likewise to be included in the bourgeois class are those sections of ‘senior management’ that are employed in big Cypriot companies, which on account of their size have a vertically integrated structure and personnel performing purely managerial tasks: the number of people involved comes to around 400 (four managers on average for every productive unit employing 250 people[8]), that is to say approximately 0.1% of the potential workforce. To these must be added the managerial personnel of state enterprises and the broader public sector, numbering an estimated 4,100 people[9], i.e. 1.0% of the potential workforce.

Correspondingly there is the petit bourgeois class which can be subdivided into the traditional and new petit bourgeoisie. To calculate the size of the traditional petit bourgeoisie, we used the Cyprus Companies Registry (see Table 2 in the Appendix), from which we ascertained that there are 87,884 employers with small businesses, usually family businesses, employing up to nine workers, who classified as traditional petit bourgeoisie (small traders, artisans, etc.). Some of these small employers would not have declared themselves as such in the 2011 census, given that in Cyprus the total number of employers barely comes to 15,900. The reason for this specific discrepancy is that some businesses have ceased operations, some are registered without functioning and some employers own more than one business. Given this, if we conclude that finally 2/3 (58,000) of registered businesses have one employer at the head of them, then 13.9% of the potential workforce belongs to the traditional petit bourgeoisie.

The new petit bourgeoisie is comprised of every kind of self-employed person who is not subject to exploitation or domination. In aggregate, from the ‘self-employed’ category, they amount to 5.9% of the potential workforce. To that figure, another 14.4% must be added from the category ‘public employees’ (2.4% of the potential workforce is to be included in the ‘senior’ personnel category, 11% from the category ‘technically qualified’ working full time, along with 1.0% in ‘uniformed’ occupations (e.g. police and military). In reaching this conclusion we took into account both the repressive role that is played by the said ‘uniformed’ sectors and the fact that some of the ‘technically qualified’ are employed part-time and so, irrespective of the position they may attain, appropriate a smaller proportion of the overall wealth, which does not exceed the cost of reproduction of their labour power. .

Farmers can be divided into three large social categories: wealthy, medium and poor, according to the approach we adopted in the preceding section of our paper. As a basis for further calculation and classification we have utilized data on the distribution of the lands under cultivation. But a paradox is to be observed here, which has to do with the number of farmers. Specifically we should note that while category (6) of Table 1 ‘Agricultural and Fishery Workers’ includes 5,145, or 1.2%, of the potential workforce, exposing a near total de-agriculturalization of Cypriot society, the 2010 agricultural census mentions 38,394 farms belonging to natural persons, or 9.2% of the potential workforce. The difference is of course too great to be attributable to the familiar statistical deviation. Our view is that in reality a great number of the proprietors of smallholdings either do not cultivate them at all or cultivate them only to a very limited extent, extracting additional income but without agriculture being their main mode of employment. Thus, on the 13,721 farms up to five decares in size, 26,027 proprietors and members of their households, together with 177 farmhands, engage in farming an average of 19.9 days per year. Correspondingly, on the 14,896 properties that range between five and 20 decares in size, 31,373 proprietors and members of their households, together with 395 farmhands, engage in farming 39.4 days per year.

It emerges from the above that, in general terms, allotments that are less than 50 hectares of land are so small that most of the farmers are obliged to have another job as their principal occupation. By contrast, the 9,616 proprietors of medium sized allotments, between 30 and 99.9 dectares in area, who work on average 90 days a year with their family members and 105 days a year with their farmhands, may be regarded as being part-time farmers, or to be more precise some of them have farming as their chief occupation and others do not. Finally, the 3,800 proprietors of properties more than 100 decares in area and who work with members of their households on average 154 days a year and 199 days a year with their farmhands are mostly full-time farmers.

In conclusion, we estimate that, of the 3,800 proprietors and members of their households owning more than 10 decares, 70%, that is to say 2,660 people or 0.6% of the potential workforce, are employed in farming as their chief occupation and are to be included in the category of wealthy farmers. Correspondingly, we judge that, of the 9,616 proprietors and members of their households who own allotments between 30 and 100 decares in size, 35%, that is to say 3,366 people or 0.8% of the potential workforce, are employed in farming as their chief occupation and belong to the medium farmer category. Finally, we estimate that, of the 64,317 proprietors and members of their households who own allotments up to 30 decares in size, 25%, that is to say 16,079 people or 3.9% of the potential workforce, have farming as their chief occupation and belong to the strata of poor farmers.

The category of employees, which is numerically the strongest (78% of the potential workforce), is made up primarily of members of the working class. If from that 78% we deduct the 14.4% we have characterized as belonging to the petit bourgeoisie, along with the 1.1% who are salary earners but also members of the bourgeoisie, we end up with a figure in the order of 62.5%. But we have argued that a sizeable proportion of the 58,000 owners of small enterprises, around 48,000 or 12%, do not declare themselves as such, and so must also be deducted from the proportion of employees belonging to the working class. But this figure too must be treated cautiously, given that some employees are in fact relatives, ancillary members of a family business, and as such belong to the traditional petit bourgeoisie. Not having at our disposal more detailed data and taking into account AKEL’s corresponding calculations[10] for the 1990s, we conclude that around 13% of the potential workforce can be included in this category. Finally, the 4.1% difference between the apparent 1.2% of agricultural workers (category 6) and the actual 5.3%, which is the statistic we arrived at, must also be deducted from the total of employees. We thus come up with a figure of 33.4% for the working class of Cyprus.

Nevertheless, what must be underlined is that there is a hidden element in the statistics for the working class, namely the number of unemployed. Undoubtedly this 11.0% should not be completely included in the working class category given that sections of the new petit bourgeois have also fallen victim to unemployment. Nevertheless if we take into account that 30.4% of the total unemployed have tertiary educational qualifications, we conclude that the 11.0% of the unemployed are to be divided into 7.7% who are members of the working class and 3.3% who are members of the new petit bourgeoisie.

Above and beyond these categories there is also a further 0.9% which is undeclared and not includable anywhere.

Therefore, we can conclude that the bourgeoisie comprises 2.1% of the potential workforce, the wealthy farming strata 0.6%, the traditional petit bourgeoisie 26.9%, the new petit bourgeoisie 23.6%, the intermediate farming strata 0.8%, the poor farming strata 3.9% and the working class 41.2%, with a further 0.9% remaining unclassified.

8.Discussion

One preliminary conclusion that can be extracted from the preceding theoretical and empirical exposition is that in the Republic of Cyprus the ruling class comprises around 2.7% of the potential economically active population (bourgeoisie and wealthy farming strata), a majority (51.3%) offer social support to this ruling class (traditional petit bourgeoisie, new petit bourgeoisie and intermediate farming strata), while on the other side of the capital – labour contradiction, is the working class (41.2%), with the poor farming strata as potential allies (3.9%).

Of course it should be mentioned at this point that these findings are a grosso modo outline of Cypriot society, the first to be attempted for 20 years. Unfortunately, what is missing are the more specialized studies of the kind that have been carried out on Greek society, which would help us to arrive at more precise conclusions.

From the Cyprus Statistical Service’s data, we detect a relative polarization between the two basic classes and their allies, which however differs from the situation in which each side would number approximately half the potential workforce. On the contrary, the ruling class, together with its social supports, clearly outnumbers the so-called subaltern classes. This fact amounts to a direct antithesis with the prevailing situation in Western capitalist countries. The relevant study that we carried out on the social structure of various countries of the developed West at the beginning of the 1990s indicated that the working class comprised approximately two-thirds of the workforce, and the bourgeoisie, along with its supportive classes, comprised approximately 1/3: in the USA the working class comes to 65%, in Canada it approaches somewhere between 62% and 65%, in the United Kingdom 65% to 70%, in Western Germany between 62% and 70%, whereas in Japan it is estimated to be between 73% and 77% (Sakellaropoulos, 2002, pp. 123-124).[11]

Returning to Greece, in the relevant study we conducted on the social transformations brought about by the recent crisis we ascertained that in 2009 (fourth quarter) the social structure was as follows: bourgeoisie 3.2%, wealthy farming strata 0.7%, traditional petit bourgeoisie 7.3% , new petit bourgeoisie 29.5%, intermediate farming strata 1.9%, poor farming strata 7.4%, and working class 49.1% (Sakellaropoulos, 2014, p. 307). The bourgeoisie and its supporting classes thus comprised 42.6% of the population, and the working class, together with the poor farming strata, is 57.4%. This shows that, prior to the crisis, Greece was somewhere between Cyprus and the other Western countries. Data from within the crisis period (2014 first quarter) indicate that the bourgeoisie comprised 2.8%, the wealthy farming strata 0.6%, the traditional petit bourgeoisie 6.9%, the new petit bourgeoisie 25.3%, the intermediate farming strata 1.4%, the poor farming strata 7.1% and the working class 55.3% (Sakellaropoulos, 2014, p. 307). Thus the bourgeoisie and its supporting classes comprised 37.2% and the working class together with the poor farming strata 62.8%. We see that the crisis has brought significant changes to Greek society, which is coming to resemble Western societies, with the important distinction of having, for historical reasons, a comparatively large farming population.

Consequently the Cypriot social formation presents some very important divergences from developments in the West but also in Greece, displaying characteristics of a more ‘transitional’ type of society, with a large number of intermediate strata alongside a clearly smaller working class. Transitional societies evolve out of the ‘traditional’ societies of the early period of capitalism where, despite the hegemony being exercised by the bourgeoisie in alliance with the petit bourgeois strata, the farming strata remain in the majority.

The Cypriot social formation can be attributed to the presence of small businesses in the post-war period, in both industry and trade and services. Admittedly a clear tendency towards concentration of capital is also to be noted. For example there are only nine processing enterprises employing over 250 workers and 4,990 which employ from zero to nine, but developments such as the de-agriculturalization of the economy (contraction in the numbers of those employed full time in farming from 38.3% in 1973 to 5.3% in 2011) and the expansion of trade, tourism and other services (employment in the tertiary sector rose from 35.5% in 1973 to 55.7% in 2011) paved the way for the establishment of a basic network of small to medium businesses (for example, in 2011 there were 15,784 businesses engaged in trade with up to nine employees and 4,669 corresponding businesses specializing in catering and accommodation, and it is noteworthy that there were 1,282 similar insurance and real estate companies and 1,455 legal and accounting offices, 1,241 architects, 1,810 agencies providing educational services, 2,586 concerned with human health and 2,946 barbers, hairdressing salons and beauty salons) all setting the pattern for social stratification in Cyprus.

Appendix

References

AKEL (1996) The Class Structure of Cypriot Society. Economic and Social Changes, Nicosia (in Greek).

Althusser, L. (1976) ‘Ideologie et Appareils Ideologiques d’ Etat,’ in Positions, Paris: Editions Sociales, pp. 67–125.

Aronowitz, S. (2002) ‘How Class Works. Power and Social Movement,’ London: Yale University Press.

Atkinson, W., (2015) Class, Cambridge: Polity.

Balibar, E. (1985) Classes, in Labica, G and Bensussan, G. (eds) Dictionnaire Critique du Marxisme, Paris: PUF, pp. 170–179.

Bensaid, D., (1995) Marx l΄intempestif, Paris: Fayard.

Berthoud, A. (1974). Travail productif et productivité du travail chez Marx, Paris: Maspero.

Bieler, A. and Erne, R. (2014), ‘Transnational Solidarity? The European Working Class in the Eurozone Crisis’, Socialist Register 2015, Vol. 51, pp. 157–177.

Bihr, A. (1989) Entre Bourgeoisie et Prolétariat, Paris: L’ Harmattan.

Billiteri, T.J. (2009) ‘Middle-class squeeze: is more government aid needed?’ CQ Researcher Vol. 19 No. 9, pp. 243–262.

Bouvier-Ajam, Μ and Mury, G. (1963) Les classes sociales en France, Paris: Editions Sociales.

Burbach, R. and Robinson, W. (1999) ‘The Fin De Siecle Debate: Globalization as Epochal Shift,’ Science & Society Vol. 63, No. 1, pp. 10–39.

Carchedi, G. (1977) On the Economic Identification of Social Classes, London: Routledge.

Carter, B. (1986) Review of E.O. Wright’s Classes, Sociological Review Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 686–688.

Chibber, Vivek (2014) ‘Capitalism, class and universalism: Escaping the cul-de-sac of postcolonial theory’, in Panitch, L, Albo, G., Chibber, V. (eds) ‘Registering Class’, Socialist Register Vol. 50, pp. 63-79.

Christodoulou, D. (1995) ‘Where the Cypriot “miracle” has not reached,’ in Peristianis, N. and Tsangaras, G. (eds), Anatomy of a Transformation (in Greek), Nicosia: Intercollege Press, pp. 35–55.

Colliot-Thélène, C. (1975) ‘Contribution à une analyse des classes sociales.’ Critiques de l' Economie Politique no. 21, pp. 93-126.

Croix de ste, G.E.M. (1984) ‘Class in Marx's Conception of History, Ancient and Modern,’ New Left Review, no 146, pp. 94-111.

Dallinger, D. (2013) ‘The endangered middle class? A comparative analysis of the role played by income redistribution,’ Journal of European Social Policy Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 83-101.

Gramsci, A. (1972) The intellectuals (in Greek), Athens: Stochastis.

Johnson, Τ. (1977) ‘What is to be known?’ Economy and Society, Vol. 6, No. 2., pp. 194-233.

Lenin, V.I. (1977) A Great Beginning, Peking: Foreign Languages Press.

Lytras, A. (1993) ‘Introduction to the theory of Greek social structure’ (in Greek), Athens: Livanis.

Malakos, T. (1991) ‘On “analytical Marxism” or why Marxists should be interested in analytical Marxism and critical of it.’ Theseis No. 36, pp. 51-74.

Martin, R. (2015) ‘What Has Become of the Professional Managerial Class?’ in Panitch, L. and Albo, G. (eds), ‘Transforming Classes,’ Socialist Register, Vol. 51, pp. 250-269.

Meiksins, P. (1986) ‘Beyond the Boundary Question,’ New Left Review, No. 157, pp. 101-120.

Milios, G. (2002) ‘The question of the petit bourgeoisie. A single class or two discrete class aggregations?’ (in Greek), Theseis No. 81, pp. 59-80.

Nagels, J. (1974) Travail collectif et travail productif,’ Bruxelles: Εditions de l' Université de Bruxelles.

Palmer, B. (2014) ‘Reconsiderations of Class: Precariousness as Proletarianisation,’ in Panitch, L, Albo, G., Chibber, V. (eds) ‘Registering Class’, Socialist Register, Vol. 50, pp. 40-62.

Poulantzas, N. (1979) Classes in Contemporary Capitalism, London: Verso.

Radice, H. (2015) ‘Class Theory and Class Politics Today’, Socialist Register 2015, pp. 270-292.

Resnick, S. and Wolff, R.D. (1982) ‘Classes in Marxian Theory,’ The Review of Radical Political Economics, Vol. 13, No. 4, pp. 1-18.

Resnick, S. and Wolff, R.D. (1986) ‘Power, Property and Class,’ Socialist Review, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 97-124.

Robinson, W. and Harris, J. (2000) ‘Towards a Global Ruling Class: Globalization and the Transnational Capitalist Class,’ Science and Society, Vol. 64, No. 1, pp. 11-54.

Robinson, W. (2001) ‘Social Theory and globalization: The rise of a transnational state,’ Theory and Society Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 157-200.

Robinson, W. 2001/2002, ‘Global Capitalism and Nation-State-Centric Thinking – What We Don’t See When We Do See Nation-States: Response to Critics,’ Science & Society, Vol. 65, No. 4, pp. 500-508.

Robinson, W. (2012) ‘“The Great Recession” of 2008 and the Continuing Crisis: A Global Capitalism Perspective”, International Review of Modern Sociology, Vol. 38, No. 2, pp. 169-198.

Sakellaropoulos, S. (2001) Greece after the Dictatorship (in Greek), Athens: Livanis.

Sakellaropoulos, S. (2002) ‘Revisiting the Social and Political Theory of Social Class,’ Rethinking Marxism, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 110-133.

Sakellaropoulos, S. (2014) ‘Crisis and Social stratification in 21st century Greece’ (in Greek), Αthens: Topos.

Vaughan-Whitehead D., Vazquez-Alvarez, R. and Maitre, N. (2016) ‘Is the world of work behind the middle-class erosion?’ in Vaughan-Whitehead, D. (ed.) Europe’s disappearing middle class. Evidence from the world of work, Cheltenham: Edward Elgae and Geneva: International Labor Office, pp. 1-52.

Vergopoulos, K. (1974) ‘Capitalisme difforme,’ in Amin, S. and Vergopoulos, Κ. (eds) La question paysanne et le capitalisme, Paris: Anthropos, pp. 63-294.

Wright, E.O. (1976) ‘Class boundaries in advanced capitalist societies,’ New Left Review, No. 98, pp.3-41.

Wright, E.O. (1987) Classes, London: Verso.

Wright, E.O. (1997) Class Counts: Comparative Studies in Class Analysis, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[1] For a recent comprehensive presentation of the basic content of the Marxian and Marxist problematic on the question of social classes, see Atkinson, 2015, pp. 19-39.

[2] For the importance of the role of the Ideological State Apparatus see Althusser, 1976.

[3] For why more than nine workers are needed for there to be extended reproduction of capital, see Sakellaropoulos, 2001, p. 170.

[4] Something similar might be said of the precariousness in employment. The spread of the regime of temporary employment, something concerning not only the secondary but also the tertiary sector (and in some cases even the primary), is an outcome of class struggle involving power correlations that allow this phenomenon to grow. It is not a hybrid new social class (Palmer, 2013, pp. 42-43) but an internal stratification within the working class. Class is constituted through exploitation and the drive for domination, whereas employment status is modifiable. On the issue of the fragmentation of the working class see Radice, 2014, pp. 278-279.

[5] For a more political extrapolation of Robinson's views and the need for universalization of social tensions against a universal capital, see Chibber, 2014. For the problems faced by potential pan-European resistance to EU policies, see Bieler and Erne, 2014, pp. 160-168.

.

[6] By ‘potential workforce’ we mean the aggregate number of working employees and the unemployed.

[7] The Cyprus Statistical Service’s 2011 census of companies recorded 92,204 companies, of which 4,320 registered more than nine employees.

[8] According to the Company Register there were 108 such businesses (see Table 2 of the Appendix).

[9] This is the figure that emerges if we take it into account that according to the 2008 register of civil servants there were 63,384 civil servants working on various contractual bases whereas in 2011, according to the director of the statistical service, they had risen to a figure of 71,553 (17.2% of the potential workforce). The top level of the hierarchy is occupied by people in a position of responsibility (supervisors, directors). From the preceding analysis we concluded that directors belong to the bourgeoisie and supervisors to the new petty-bourgeoisie. Given our estimate, based on the corresponding ratios in the Greek public sector according to which there is one supervisor for every five employees and four supervisors for every director, the total number of directors comes approximately to 1/21 of the total staff, that is to say 3,400, and to them should be added the senior judiciary, revocable ministerial advisors, top-level university academics and the political personnel of the national and local governments, bringing us to a total of 4,100.

[10] The AKEL study gives a corresponding figure of 13% for the beginning of the 1990s (ΑΚΕL 1996: 96).

[11] In the context of the Marxist theoretical model, we do not know of any comparable comparative study. On the contrary, there are a number of studies that approach classes as economic rather than social categories. In other words income distribution is the key criterion and not relations of domination and exploitation. The most recent study to adopt this approach is that of Vaughan-Whitehead, Vazquez-Alvarez and Maitre (2016), which deals with changes in the size of the middle classes between 2004-2006 and between 2008-2011 in EU countries, Iceland and Norway. In it, households with between 60% and 120% of the median income are defined as middle class. The findings indicated that although Cyprus, Spain and Estonia saw a dramatic expansion of the middle class in the preceding period (2004-2006), between 2008 and 2011 they experienced a decrease. Similarly, there are countries where there was continuation of an already noted contraction of the middle classes, such as Greece, Germany and the UK. Finally, in France, the Czech Republic and Sweden, where an increase in the core middle class was registered between 2004 and 2006, a reverse trend was noted between 2008 and 2011 (Vaughan-Whitehead, et al., 2016, p. 15). For research on the corresponding methodology, see Billiteri, 2009 and Dallinger, 2013.