The recent economic crisis in Greece and the strategy of capital

The recent economic crisis in Greece and the strategy of capital

by Spyros Sakellaropoulos

- Introduction

In this article it is proposed to examine the dimensions of the recent economic measures taken in Greece in response to the increase in the deficit and the public debt. The basic approach will be to demonstrate that reality is entirely different from what is presented in official rhetoric. Starting point for the scenario is the expansion of the global crisis through the countries of the Economic and Monetary Union in conjunction with questions arising out of the existence of a common currency for national formations with different productivity, the specific role of financial capital in the overall conjuncture, but also maintenance of the hegemonic position of Germany within the EU. That said, as far as Greece is concerned the problem of the deficit and the debt is employed as a bridgehead for the deployment of aggressive class policies. The reason for this has to do with Greek capitalism’s inability to continue to be integrated in the same way as before into the international division of labor. Failure to adopt a technologically and sectorally restructured model that could assist in raising Greek competitiveness against the powerful imperialist formations inevitably leads to an attempt to solve the problem through shifting the relevant cost onto the popular strata through the recent economic measures (reduction in salaries, greater labor flexibility, loosening of restrictions on firing, reduction in pensions). Stated somewhat differently, we are currently experiencing the most aggressive campaign of the bourgeois state, on the economic level, since the end of the Greek Civil War. The effort is centred on rapid transfer of wealth from labor to capital with an intensity unprecedented in modern times. Through this project the Greek bourgeoisie calculates that it will acquire the capacity to deal with the pressures to which it is being subjected by capitalist formations of higher productivity. .

2. The General Context

The advent of the global economic crisis has brought to the surface the structural contradiction that was present from the outset in the endeavour of the single European currency. As acknowledged even by Paul Krugman (Krugman 2010), who is the last person to be suspected of espousing Marxist views, it was predictable that at some point the establishment of a single currency by countries with entirely different levels of productivity would bring to light a host of contradictions. These are contradictions that have to do with the different structural characteristics of each country, the uneven rates of capital accumulation, the unequal contributions to international competitiveness, leading not only to differentiations in the rates of inflation, an increase in GNP and a spiraling of public debt but also, and above all, to differentiations in international specialization of the national productive systems (de Grauwe 2009).

In this context, in conditions of capitalist development, from the moment that it cannot be used as an instrument for devaluation, the single currency is used as a lever for exerting pressure for modernization of the less competitive capitals. Of course what is involved is not a neutral procedure and on the basis of the law of uneven development the tendency will be for the differences between national capitals generally to become greater. It is for precisely this reason that Germany, as the economically most powerful formation of the European Union, chose the solution of the euro. It judged that its superiority in competitiveness, reinforced by inability of the individual member states to implement devaluations, would result in protracted export growth, as indeed occurred. That said, the worsening financial crisis had the effect of partially, but not totally, modifying the existing economic and political context. Conditions of recession were generated in which the competitiveness deficit became ever more obvious, with the result - among much else – that financial indicators were disrupted and the cost of borrowing increased. This occurred because of fall in consumption expenditure, leading to a cutback in state revenues and an increase in the deficit as a percentage of the smaller GNP. The situation was aggravated by the fact that the fall in production triggered an increase in unemployment, so that there was an even greater shortfall in public revenues and more frequent resort to borrowing to cover basic needs. The situation is exacerbated through the fact that the fall in production generates an increase in unemployment, resulting in an even greater shortfall in public revenue. The absence of elementary redistributive policies with the potential to offset the uneven development shows nothing more or less than that the EU is not a confederation, much less a federation, but a sui generis institutional conjunction of national formations competing with each other for the largest possible appropriation of produced wealth.

This new reality will lead the Greek bourgeoisie to a change of model vis à vis its mode of insertion into the international division of labor. To be able to understand the content of this change of model it will be necessary to demystify certain myths that the ruling class seeks to impose through its political representatives and through the shapers of public opinion.

3. Myth 1: There is a certain deviant quality to the Greek economy necessitating implementation of such extreme austerity measures

Truly, if one takes seriously what is said in the mass media, in official governmental circles and also among a certain section of organic intellectuals, in their endeavour to justify the violence of the measures being taken, one could conclude that what is taking place in the Greek economy is something unprecedented, making it an extreme case by Western standards. But the available data does not support such a conclusion. For a start the Greek state is not the most wasteful in Europe. Its operating costs correspond to 17.3% of Greek GNP, as against 19.9% for Germany, 24% for France and 23.7% for Great Britain, and a European average of 21.8% (Vergopoulos, 2010). As far as deficits are concerned, the USA in 2009 ran a 12.5% deficit, Japan a 10.5% deficit, with the average for the countries of the Eurozone 6.6%.

As for debt, it may indeed be the case that the Greek debt in 2009 reached the level of 113.4% of GNP, but economically very robust Japan finds that its debt has skyrocketed to the level of 197.2%[1]. This situation appears in a very different light if we take into account the overall debt of every country (that is to say the total sum borrowed by the state, businesses and private individuals). According to official IMF statistics, overall Greek debt amounts to 179% of GNP, at a time when the EU average is 175% and Holland presents an overall debt of 234% of GNP, Ireland 222%, Belgium 219%, Spain 207%, Portugal 197%, Italy 194%. Corresponding findings emerge from an examination of the figures for external debt (that is to say the debts of the state, businesses, and private individuals to foreign banks, bearing in mind that part of the debt is to banks in the same country): Among the so-called PIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Greece, Spain), Ireland owes 414% of GNP, Portugal 130%, Greece 89.5% and Spain 80% (Delastik 2010a).

Moreover, Greece may appear to have a great need to borrow money but the situation for many other Western states is no different. Specifically, the country’s new loan requirements for 2010 are expected to amount to 50 billion euros, at a time when other “small” countries such as Belgium and Holland are each programmed to be borrowing 100 billion euros. And if for foreign banks the risk of lending 50 billion euros to Greece is considered high, what can be said of Germany, which admittedly has a GNP nine times higher than that of Greece, but is nevertheless expected to borrow 370 billion euros. And France will go as high as 450 billion euros, and Italy 400 billion, so that their in terms of a proportion of GNP their borrowing is of the same order of magnitude as Greece’s (Delastik 2010b).

What emerges from all the above? For a start, that similar economic problems are being faced by other Western countries. When this started to become clear, a second argument was enlisted: that Greece faces both debt problems and deficit problems and it is the combination of the two that has generated the present crisis situation. But this argument has two contradictions to it. The first is that countries much more developed than Greece, such as the USA and Japan are also deeply in debt and have a large deficit. The fact that they don’t face problems similar to Greece’s has to do with the fact that as much stronger economic powers they are in a position in this present phase to manage the global economic crisis in a different way. The second contradiction has to do with the fact that an overall framework of dramatization of the situation began to be generated both in Portugal and in Spain. Spain has a high level of debt. Portugal, by contrast, is not greatly indebted and its deficit is clearly lower than Greece’s. The underlying factors must therefore be sought elsewhere. As we propose to demonstrate in paragraph 6, they mostly relate to Greece’s, but also Portugal and Spain’s, lack of competitiveness, aggravated by the present global crisis and its links to the crisis of the euro, inducing the markets to withdraw confidence from the Southern European capitalisms.

4. Myth 2: The problem of Greek competitiveness arose because in recent years Greek working people have adopted a consumption model that does not correspond to the economy’s real capacities.

Expressed simply, what this means is that during the preceding period wage increases were awarded that the Greek economy could not support, with the result that production costs rose excessively and Greek products were rendered uncompetitive. The logical corollary of this myth is that from now on the income of Greek workers will have to be lowered so that the lost competitiveness can be regained.[2]

The theory of a rise in real incomes in Greece, and moreover at a rate disproportionate to the average for the EU-15 is nevertheless contentious for a number of reasons. Available figures from the European Commission do indeed indicate that between 1995 and 2008 there was a 37% cumulative increase in the purchasing power of average wages in Greece. But this figure is overestimated. For a start it assumes an average rate of inflation and not the inflation corresponding to the consumer goods and services mostly utilized by working class households. Doing the relevant calculations it emerges that this overestimation is in the order of 0.7% annually (Labour Institute of the Greek General Confederation of Labour, 2009). Moreover the average wage does not reflect the reality as experienced by the large majority of workers because the very high amounts paid to executives are included in this figure. Finally, the average of the real wage payments are not calculated for a stable number of hours but for total work time, so that overtime pay is included.[3]

The problem is that the absence of such data for the period as a whole complicates the task of drawing clear conclusions on what has befallen the great majority of wage-earners. We therefore judge that it would be safer to use different tools if one wishes to comprehend exactly what has taken place.

Starting from the share of wages in GNP we ascertain that there is a long-term trend towards contraction of this share from 56% in 1995 to 54% in 2008. The deterioration in living conditions for Greeks also appears from the fact that the proportion of household income saved fell from 14.1% in 1996 to 8.9% in 2004. Meanwhile the proportion of the population living below the threshold of poverty in 2006 came to 21%. It is interesting thathalf of the poor have an income less than 44.4% of the median income and so are very far from being in a position to be able to escape from poverty (Labour Institute of the Greek General Confederation of Labour, 2008: 210- 211). The mass resort to private borrowing perhaps becomes comprehensible from this perspective. Not being able to satisfy their consumer needs in the same manner as the preceding generation[4], a significant proportion of Greeks have turned to the banks. As a result, following the deregulation of consumer credit in 2003, household debt has gone through the roof: 28% annually for the period 2002- 2007. As a proportion of GNP the overall debt burden for Greek households rose to 50% at the end of 2009 from 34.7% at the end of 2005 (Mitrakos-Symigiannis 2009: 7)

Another indicator that registers social inequalities is taxation, where indirect taxes account for 66% of tax revenues, tax on salaries 12%, taxes on large companies 10%, on small companies 4%, and on self-employed professionals 3% (Kyprianidis-Milios 2010: 10) But the situation with the more “proportionate” direct taxes does not appear any fairer: in 2004 wage earners and pensioners accounted for 44% of income tax revenues and in 2006 50.1% By contrast while in 2004 companies paid 43% of overall income tax, by 2006 this had fallen to 36.3% (Labour Institute of the Greek General Confederation of Labour, 2008: 22- 23).

The above is comprehensible only as the result of a conscious class policy on taxation on the part of the state. And nothing different from this could be expected given that for large companies the tax burden fell from 29.9% in 2000 to 18.6% in 2006. In the same year the corresponding figures for Spain were 53.3%, for France 31.4%, for Italy 27.1%, for Cyprus 26.8%, for Belgium 21.6%, for Denmark 32.3%, for Portugal 22.6%, for England 27.7% and for the EU-25 28.7%. By contrast, the real tax burden on labor in Greece in 2000 came to 34.5% and by 2006 had risen to 35.1%. For Spain in the same year the figure for labor was 30.8%, for France 41.9%, for Italy 42.5%, for Cyprus 24.18%, for Belgium 42.7%, for Denmark 37.1%, for Portugal 28.6%, for England 25.8% and for the EU-25 36.4%. It can therefore be seen that the real tax burden on labor in Greece corresponds to the average for the EU-25, while the real tax burden on profits comes to hardly half of the EU-25 average (15.9% in Greece, as against 33% in EU-25. (Labor Institute of the Greek General Confederation of Labor, 2008: 22- 23)[5].

Τhe overall conclusion from all the above is that Greece is distinctive for its economic inequalities. This becomes particularly evident when one takes into account that the top 20% of Greeks in the scale of wealth earn 40.4% of the overall national income, while the bottom 20% of Greeks earn just 7%. By contrast in the EU15 countries as a whole this ratio in the last decade has never been higher than 4.8:1 (Labour Institute of the Greek General Confederation of Labor: 213).

General conclusion: Over the last fifteen years social inequalities in Greece have increased because the wealth produced was distributed very unevenly. Today’s problems in the Greek economy cannot therefore be regarded as attributable to (putative) increases in workers’ incomes.

5. Myth 3: (Supposed) increase in wages has led to a rapid decline in exports

Τhe first point worth emphasizing is that even if we accept, as a working hypothesis, that there has been a real increase in wages, this does not necessarily lead to a fall in competitiveness. The reason for this is that even not taking into account the methodological observations we made in the preceding paragraph, the average productivity of labor in the EU15 countries has risen more than wages (19% as against 14%). The problem therefore cannot have its origins in salaries.

It would also be a mistake to imagine that the problem of competitiveness is one that has emerged now – and even less that it has been caused by a rise in salaries.

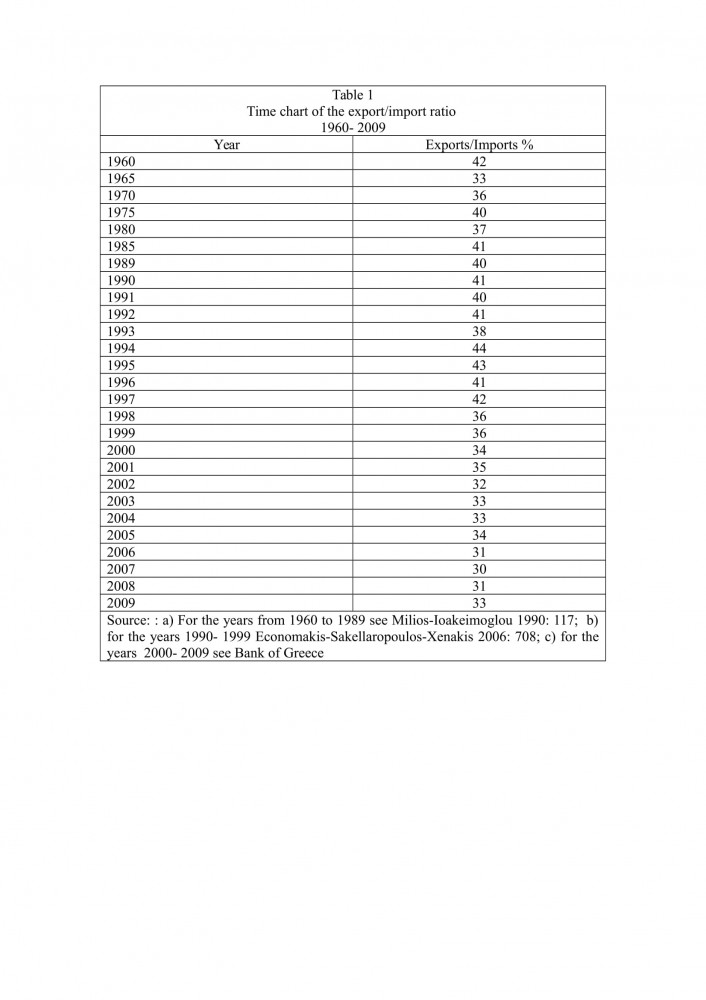

Let us examine the situation a little more closely. For us to conclude today that there is now a crisis in competitiveness means that at some quite recent point in time this problem did not exist and that therefore the Greek economy has seen significant growth. The following table, covering the last fifty years, shows no such recent change.

Τhe conclusion that emerges from the figures in Table 1 is that the export-import ratio for the period between 1950 and 1989 presents some not particularly significant fluctuations, between 1/3 and 1/2.5. The clearly higher figure for imports does reflect a lack of competitiveness but it has not resulted in anything like bankruptcy or any comparable economic misfortune. The subsequent period between 1990 and 1999 saw stabilization of the ratio at 1/2.5 Finally, for the period 2000-2009 we may conclude the following: a) A slight slippage in the export/import ratio is to be observed, causing it to fluctuate around 1/3. This development is linked to the power of the Greek social formation’s integration into the international division of labor and above all to the pressures exerted on the Greek economy as a result of the country’s entry into the Eurozone by national formations with superior productivity, but also through the use in itself of the euro as an expensive currency in transactions with countries outside the Eurozone. b) In any case, this decade does not seem to be have been characterized by any drastic reduction in exports on such a scale as to justify taking measures as drastic as those jointly decided by the Government, the European Union and the International Monetary Fund

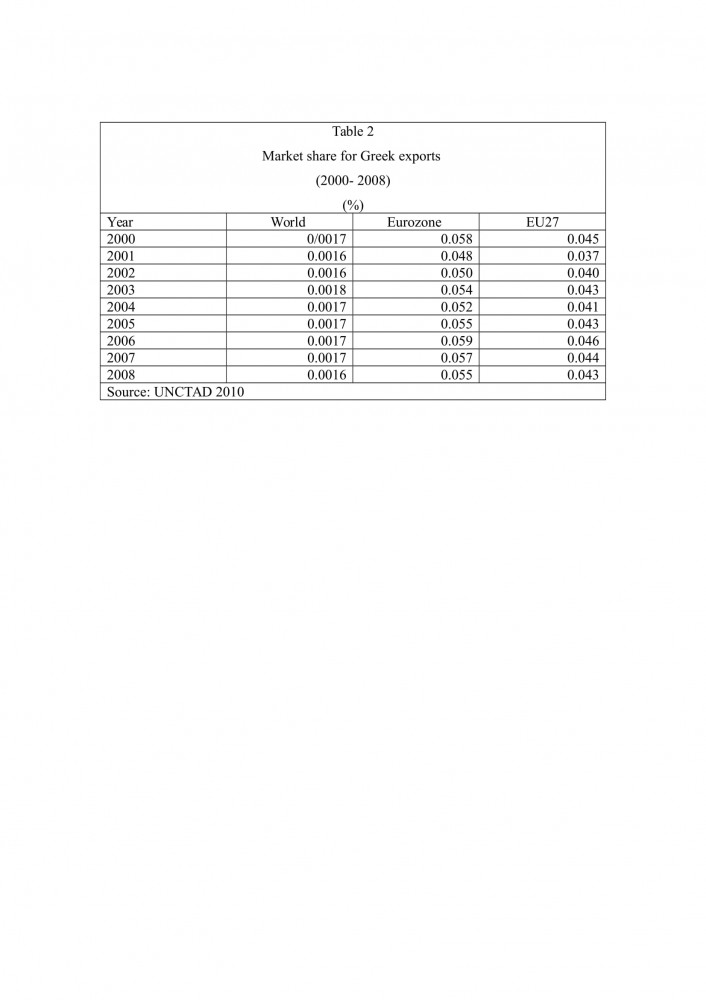

That there is no problem of plummeting Greek competitiveness can be seen from the figures in Table 2, which examines the evolution of Greece’s market share as a proportion of world exports, exports to the Eurozone and exports to all the other countries of the European Union.

We note that not even these figures provide any evidence of a profound exports crisis. There are fluctuations attributable to conjunctural factors but they all move within very specific limits. Thus, between 2000 and 2008 the Greek share of global exports fluctuates between 0.016 and 0.018 of the total, of exports to the countries of the Economic and Monetary Union between 0.048 and 0.059 and of exports to the countries of the EU between 0.037 and 0.049. It could of course be argued that even given the size of Greece these contributions are very low. We would not dispute the assertion that Greek capitalism does not derive its strength from industry, but in any case the specific existing data do not indicate any falling off in exports.

6. What is the real problem?

Τhe real problem has to do with the model for integration into the international division of labor adopted by the Greek bourgeoisie in the postwar period. The emphasis was placed primarily on shipping - in any case Greek remains steadily the number one shipping power in the world – and on development of the construction industry (above and beyond the rebuilding of the country it is worth mentioning the very significant presence of Greek construction companies in North Africa and the Middle East) and tourism and only secondarily and in a subordinate capacity in industry, and even less in industry for export. Subsequently, with the country’s entry into the EEC, the whole orientation was reinforced by Community funding. .

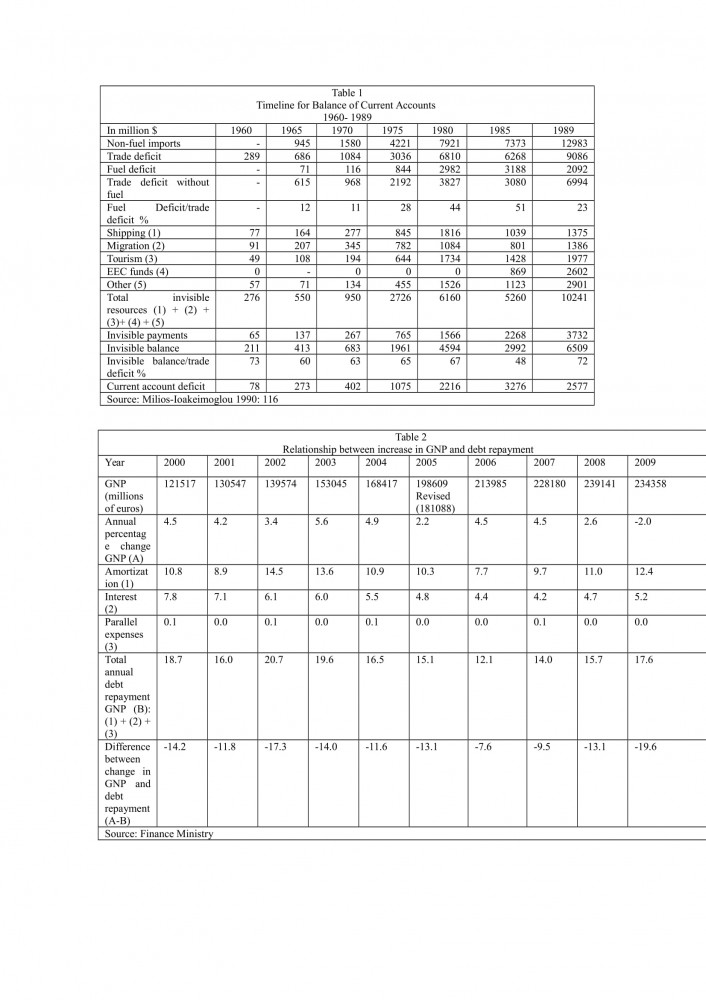

This strategy is presented in Table 1 in the Appendix. Income from tourism and shipping and EEC funding made a decisive contribution to reducing the trade deficit. To put it somewhat differently, the relative weak point of Greek capitalism , namely the competitiveness of its industry, was offset by the fact of the very strong presence in shipping, the development of the tourist industry, and funds from the EEC/EU, to a large extent channeled towards construction.

In the 1990s the even greater opening to international markets brought about by the world-wide victory of neo-liberalism (the phenomenon called by some “globalization”) intensified the pressures on the Greek economy. The solution opted for as a way of dealing with the new realities was not any kind of technological transformation or radical reshaping of the mode of organization of labor, above and beyond the adoption of certain forms of labor flexibility. On the contrary, the emphasis was placed on continuing the same model, with simultaneous intensification of the level of exploitation of the popular layers (reduction in labor’s share of the product generated, increases smaller than the rise in productivity) as well as through utilization of cheap migrant labor. It is characteristic that in a period of pronounced internationalization of capital, Greece is a country making very few direct investments abroad[6] and those it makes almost exclusively in the former “socialist” countries of the Balkans.

Entry into the European Monetary Union, the carrying out of large-scale construction works, the organization of the Olympic Games in 2004, none of this introduced any diversification into the strategy but on the contrary left it unmodified, and stronger. At the same time there was a perpetuation of various parallel ways of strengthening the power coalition and its underpinnings, such as toleration of the illegal economy (which at the dawn of the 21st century reached the level of 28.5% of the GNP, at a conservative estimate), collusion of sections of the monopolies with the state machine, with resultant overpricing of public works projects, etc.

Τhe problems began to worsen when there was a reduction in European funding, a fall in income from tourism, increase in borrowing to cover the costs generated in public works spending by favoritism towards certain corporate monopolies (the example of the Siemens scandal is typical), chronically high levels of military expenditure primarily because of broader geopolitical planning and obligations[7], excessively high public expenditures because of overpricing (one indicative example is the functioning of the hospital sector and everything associated with it: drugs, medical equipment, medical examinations conducted in private clinics because of the inability of public hospitals to perform them) changes to the shipping register for Greek shipowners, with their diversion to the shipping register of Cyprus. At the same time the entry into the EU of formations with lower labor costs (the former “socialist” countries) exacerbated the image of falling Greek competitiveness by increasing competition within the same economic integration. This is a development that was most damaging to the traditional Greek labor-intensive industries (textiles, clothing, footwear), resulting in their going bankrupt or transferring production to other countries of the Balkans. A significant role was also played by the high level of inflation in Greece compared to the average of the Eurozone countries. It might perhaps be thought that a rate of inflation in the order of 3.5% is nothing out of the ordinary and not worth bothering, about but this is not so considering that in the Eurozone countries inflation fluctuated around levels of 2.2%, an approximately 70% difference. Over the course of decade this deviation made a substantial contribution to the reduction in Greek competitiveness.[8]

Bank capital for its part attempted to pressure businesses into moving towards drastic restructuring, but this ran up again the inability of many businesses to incorporate such significant changes within the time period intervening before the international crisis broke out, often with disintegrative effects. After a certain point what was being generated was a vicious circle, with the crisis triggering cutbacks in financing for businesses, further aggravating the recession, etc.

All this was to make its presence very much felt in terms of enterprise efficiency. According to the data we have at our disposal, the marginal efficacy of fixed capital[9] was on a long-term upward trajectory until 2004, this being not unrelated to a significant increase in investments (at the highest levels of all EU countries for the period 1996-2004) in mechanical equipment (Ioakeimoglou-Milios 2005: 590-591)[10]. From that point on, every additional unit of investment in fixed capital was accompanied by a smaller increase in the product generated. This marked the end of an investment cycle characterized by the deployment of new technologies in the form of mechanical equipment imported from abroad. The cycle in question got under way in 1996 and from the 25% that was the product/capital ratio in 1995 it reached 28.5% in 2005. The rising trend peaked in 2006 and went into a downturn in 2008 (Labor Institute of the Greek General Confederation of Labor, 2008: 2009).

Τhe upshot of all this is that, aided and abetted by the global recession, from 2005 onwards the Greek economy began to show pronounced symptoms of contraction. GNP, which in real terms had been on an upward trajectory between 1996 and 2004, peaked in 2005 and then went into a sharp decline. According to predictions GNP will fall by about 2% in real terms in 2010. The annual rate of growth slowed from 4.0% in 2007 to 2.9% in 2008 and -2% in 2009. Last but not least, industrial production fell by 4.0% in 2008 whereas in 2007 it had risen by 2.7%.

At the level of state management the crisis translated into a 6.6% rise in the public deficit, which in 2008 was equal to 12.9% of GNP. This was triggered by a significant falloff in revenue, the return of taxation monies (around 4%) and increases in public expenditure (around 2%). It is characteristic that whereas for the entire period between 2002 and 2008 public revenue increased each year, in 2009 for the first time it recorded a fall of 1.1 billion euros.

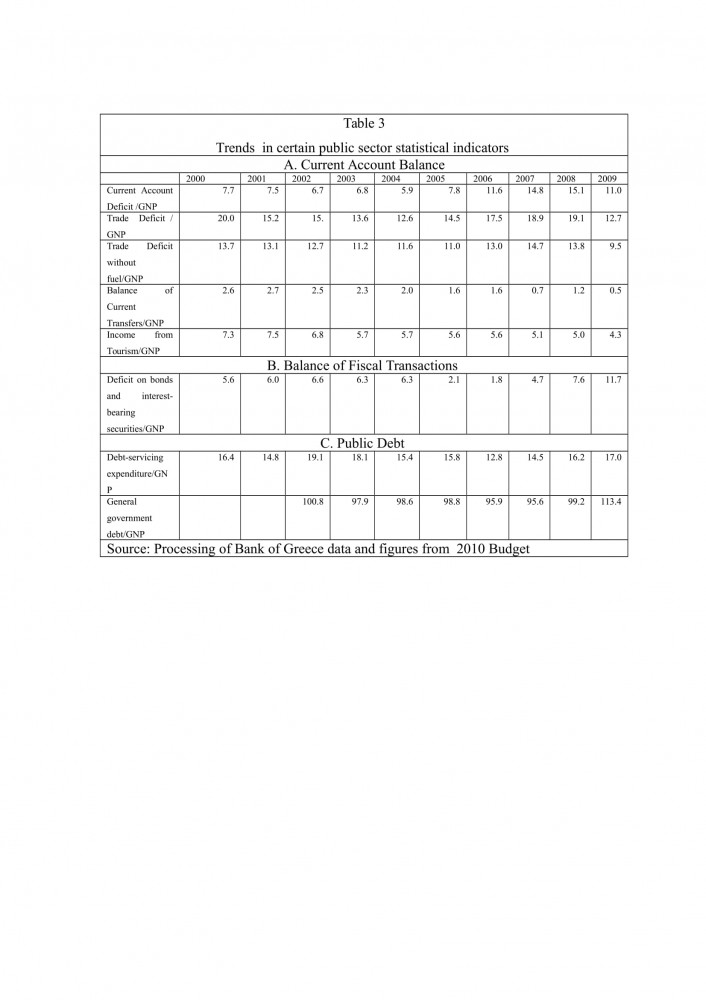

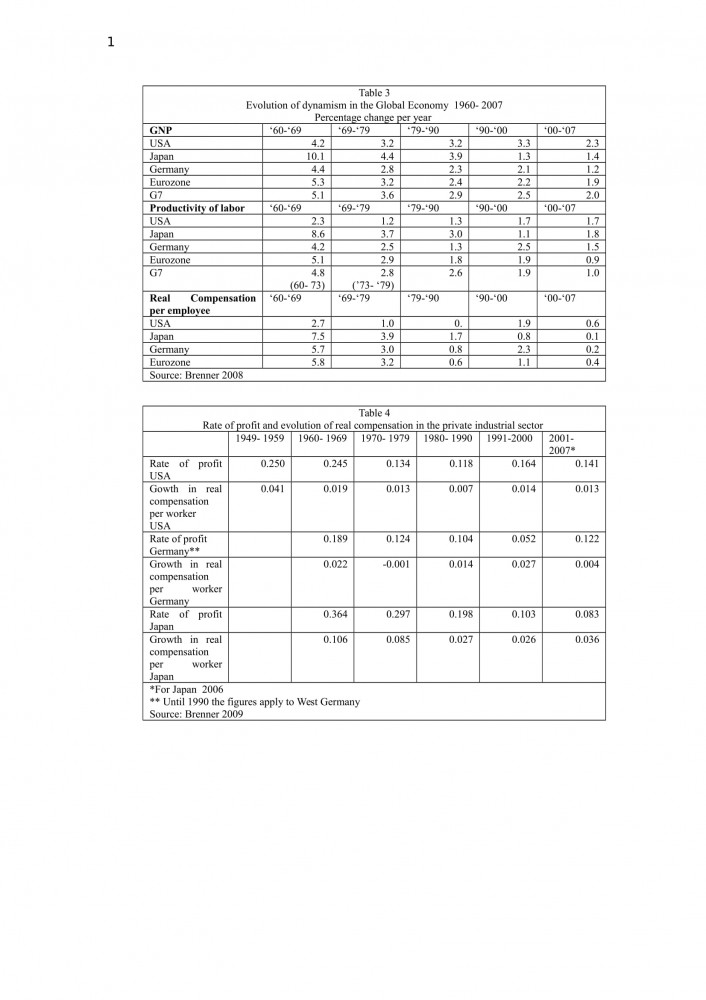

This is the background against which the data in Table 3 should be read:

We have attempted to present the existing data from the viewpoint of their correlation with GNP to avoid the latent danger of overdramatizing certain real or presumed developments.

As for the current account balance, the first finding has a bearing on the trade deficit. It is noted that the deficit was falling prior to 2004, when because of the Olympic Games significant economic development was taking place. Subsequently the deficit increases and in 2008 is back to the figures for the year 2000, falling again in 2009 on account of the de-internationalization induced by the global recession. What it is in any case faced is not an exports crisis of such dimensions as to warrant, even from a bourgeois viewpoint, such drastic measures as those that have been taken. Moreover, if it is also taken into account the question of fuel, as an energy-importing country Greece would be in a much better situation from the viewpoint of the trade balance if it did not also have to deal with this problem. Apart from this, one must take into account the relatively high rate of inflation, which in a situation of fixed nominal exchange rates led to many Greek products gradually losing competitivenesss, as did the increase in imports that was a concomitant of the economic growth and contributed to the rise in demand for imported products and investment in imported mechanical equipment (Milios 2010).

The evolution of the current account deficit follows a similar trajectory: falling until 2004, rising until 2008, falling again in 2009. But it should be noted that in the period subsequent to 2004 the deficit fluctuates around much higher levels than prior to 2004. This on the one hand again confirms that we are not faced by a sudden exports crisis and on the other shows that the other indicators are lagging even further behind. In our opinion the primary factor underlying this is the fall in tourist revenues, which is virtually continuous between 2000 and 2009 – despite the organization of the Olympic Games, which one might expect to have given a boost to tourism. This anyway is why, supposedly, the country undertook the inordinate costs involved. In our assessment the adoption of the (expensive) euro must have played a significant role in this process. The second reason is associated with cutbacks in current transfer payments, i.e. Community subsidies. We note that the termination of the Third Community Support Programme has had a negative effect on this indicator.

What should be underlined is that the crisis in the current account balance highlights a very significant deviation on the part of the Greek economy by comparison both with its own recent past and with the prevailing average in the Eurozone. This is a crisis that affects both Portugal and Spain, bringing to light similar economic phenomena there. Specifically, between 2006 and 2009 the Greek deficit was consistently in two-digit figures whereas during the same period the countries of the Eurozone were moving on average at levels between +4% and -0.8%, the Portuguese deficit was steady at 10% and the Spanish was fluctuating between 7% and 10% (European Economy 2009). The basic question is therefore neither the debt nor unemployment but the current account balance, which brings to light more general problems of productivity.

The current account balance crisis became interwoven with the global crisis complicating what had hitherto been the role of the Greek banks. Up to the time that the global crisis broke out, Greek lending institutions had been in a position to cover the current accounts deficit by borrowing from abroad so as to cater for the increased demand for foreign exchange. This was also the way they replaced the inputs for purchase of government bonds and shares which in the first years of operation of the euro helped to cover the current accounts deficit. But the lack of liquid funds from foreign banks that was one of the consequences of the crisis meant that Greek banks were unable to acquire low-interest loans, with increase in the deficit as a natural result (Pelagidis-Mitsopoulos 2010:247).

Moving on to the balance of fiscal transactions, the basic problem we detect has to with the deficit from portfolio investments and particularly bonds and interest-bearing securities. The period between 2000 and 2004 is characterized by relative stability, with the deficit being kept at levels of 5-6%. The subsequent overheating of the economy through increase in the GNP resulted in a drastic reduction of the deficit to 1.8% in 2006, but from 2007 on a rapid rise is observable, with the result that in 2009 the deficit rises to 11.7%. In our assessment this development is attributable to a number of factors: reduction in real GNP in 2009 because of the recession, an increasing resort to borrowing owing to the cost of the public works projects carried out during the preceding period, reduction in tax revenues both because of the economic contraction brought about by the global recession, which naturally affected Greece also, and because of reductions in company taxation.

As might be expected, all the above have repercussions on debt. From 2006 onwards there was an increase in expenditure for servicing of debt. In 2009 a marked increase is to be observed in indebtedness as such. From 2007 onward debt increases significantly in absolute terms[11]. On this we have two observations to make:

The first is that increase in debt is a serious question, not easily to be brushed aside. It is a major problem for the Greek bourgeoisie, exposing the crisis in the model of capitalist development that had been implemented in the previous (many) years. The data in Table 2 of the Appendix show that while the decade between 2000 and 2009 is characterized by high rates of growth, in essence this does not improve the situation of the economy, because the additional revenue is channeled into meeting interest payments and if we also take into account payment of amortization, a deficit is generated that necessitates a renewed resort to borrowing. The crisis of 2009, which was to be characterized by negative growth, propelled the Greek economy much further into deficit. The overall picture becomes darker when one bears in mind that a large number of expired loans will have to be paid in 2011-2013, with the average time period for repayment of loans falling from 10 years to 7 years.

Nevertheless, and this is the second observation, we are not speaking here of something historically unprecedented, nor should parallels be drawn with 1898 or 1932, when historical conditions were entirely different (the absence of a common currency, a lesser degree of internationalization of the Greek economy and so a lesser effect of the aforementioned two bankruptcies on the international economy). Besides that, it is evident from Table 3 that in 2002 and 2003 the situation was clearly bleaker, because debt servicing costs were higher. Moreover almost all of the debt (97%) is in euros and so is not influenced by the fluctuations of the euro against the dollar, the yen and the pound, and no question arises of there being insufficient reserves of foreign exchange (Vergopoulos 2009). 75% of it is held by European banks, which for obvious reasons do not want to see a collapse of the Greek economy.[12] Finally, 75% of the debt is with fixed - and 25% with fluctuating - interest rates, so that the effect of the markets is largely confined to new loans (Stathakis 2010).

7. The three key dimensions of the question

Our basic position is that things took this turn because the real problem on the one hand involved the crisis of strategy of Greek capital but on the other triggered wider changes. We should bear in mind that Greece is a country of the Eurozone, so that the effects of this specific crisis, which is unfolding within the context of global recession, could not remain merely “local”.

As far as the crisis of Greek capitalism is concerned, the Greek ruling class’s inability to forge an alternative bourgeois strategy is seen in a negative light by the international money markets, which for their part initiate a process of withdrawal of confidence of the financial houses from Greek capitalism. In other words the real problem was neither the deficit nor the debt (in any case as we have shown, similar problems are being faced by other countries) but two entirely different issues: the downgrading from the international markets being experienced by Greek capitalism and the more general international dimension of the crisis. Let us examine these two issues more closely.

In relation to markets, the assessment is that Greek capitalism in the coming period will very likely be downgraded within the international division of labour so that investment in it involves certain dangers. It is for this reason that Greece is now borrowing at such high interest rates.[13] This has its effect on the banking system: the banks are looking for capital abroad to sustain demand, but Greece’s low credit rating necessitates the imposition of high interest rates on its borrowing (Pelagidis-Mitsopoulos 2010: 248). Why is this happening? Channeling of capital into the fiscal sector is predicated on predictions that entail a significant element of risk: the markets make an assessment of future production, positing a right to the future income that is expected to be generated by this production. The problem is that there is no way of ensuring that these profits will in fact be realized. From the moment that the markets form the impression that the conditions prevailing in a country (and in this there are included both factors like the strategy of the bourgeoisie and the resistance to it that is mounted by the subaltern strata) do not guarantee the initially predicted profitability, they then “downgrade” the country in question through mass outflow of capital and/or a rise in interest rates (Ioakeimoglou 2001b).

In its international dimension, the Greek crisis has to do both with the euro and with inter-imperialist antagonisms. The aspiration of a number of European countries was to create a strong currency that would gradually come to function as the global reserve currency. And the euro did indeed make extremely satisfactory progress, winning a substantial share of the global markets. In the international bond markets in December 2007 the euro accounted for 32.7% of their overall value, as against the 21.7% of 1999. By contrast, the dollar’s share fell from 46.8% in 1999 to 43.2% in 2007. In 2004 19% of transactions in specific fiscal products (spots, swaps, outrights) were in euros, with the predominant dollar notching up 44% of the market, the pound 8.5% and the yen 10%. Most significant, however, was the presence of the euro in total global reserves. According to the relevant statistical data, in 2007 63.9% of global currency reserves were in dollars (as against 71% in 1999), with the euro’s share in the vicinity of 26.5% (as against 17.9% in 1999), sterling as low as 4.7% (as against 2.9% in 1999) and the yen 2.9% (as against 6.8% in 1995) (Melas 2010: 35). The euro therefore succeeded in demonstrating a considerable dynamism, without of course becoming main reserve currency, but imposing certain limitations, albeit unevenly, on the predominance of other currencies. This development was to encounter a reaction from the rival formations, the more so because from the time of its creation, the revaluation of the euro was primarily against the dollar and the pound.

The crisis in Greece has been used not only as a device for extracting speculative profit from lending at exorbitant rates of interest but also as means of converting Greece’s crisis into a crisis of the euro[14]. Inside the Eurozone this has taken the form of real conflicts between Germany and France[15]. Perceiving the emerging danger, France wished to help Greece, not of course out of the kindness of their heart but out of apprehension that the crisis could then spread to Portugal and Spain, triggering the collapse of the common currency. Germany for its part judged that its particular interests were best served by the existing situation whereby, as the country with the highest productivity it had achieved domination of the Eurozone as an exporting power. To put it somewhat differently, further export penetration by Germany was based not on the nominal exchange rates of the basic reserve currencies but on technological innovation that would enable it to maintain its leading position in specific branches of industry (automobile manufacturing, chemicals, mechanical equipment) in the broader capital goods sector while imposing a ceiling on wages[16] (Horafas 2010: 12- 13). As a result, between 2000 and 2010 Germany will have accumulated a very large current accounts surplus. Just for 2007 it was in the order of 8%. This occurred because within this time period there was a very large growth of exports while domestic demand remained stationary, registering an almost imperceptible rise of 0.2% annually. The insignificant increase in domestic demand can be explained by the stagnating real incomes of workers, a rise of 0.4%, much smaller than the increase in productivity. The final result was that within the space of a decade a product would cost 25% more if it had been produced in Greece, Italy, Portugal or Spain, 23% if produced in Ireland and 13% if produced in France, while in Germany its price remained stable (Fleischbeck 2010: 57).

It was therefore thought in Germany that any assistance towards Greece would have the effect of reducing the profits of German companies because it would tend to offset differences in productivity and generate domestic problems in Germany, its export triumphs being contingent on policies of austerity to an extent unknown in the other countries of the Eurozone. In other words German capitalism agreed to be part of the euro on the calculation that when other formations surrendered the advantages of being able to devalue, they would be unable to compete with Germany’s high productivity and wage restraint. When the consequences of this policy started to become evident, the assessment was that it was preferable for the Greek economy to be placed under pressures rather than that there should be a questioning of the totality of the arrangements that had brought such great gains to Germany. To put it somewhat differently, with its adoption of the euro, Germany appeared to be making a decision to concentrate its activities inside the Eurozone. It is therefore no surprise that 43% of its exports should be to other countries within the monetary union.

There is of course an additional – third - dimension which has not fully crystallized but which we judge will in the near future become a matter of concern for more radical analysts. Starting from Greece, whose profile in the West by the way has always been unorthodox in the sense of having a more dynamic workers’ movement, strong leftist traditions and a political system tilted towards the left, a transition is evidently being sought to a new phase in the politics of the developed capitalist formations.

Today’s crisis shows that there are no countervailing trends to the falling tendency in the rate of profit, not even through changes in the organization of production (implementation of flexible work relationships) nor through technological innovation (use of informatics in production, new forms of automation, biotechnology). At the same time, the fact that a significant part of expanded accumulation has been associated with the development of services, that is to say with labour-intensive workplaces, has placed limits on increases in productivity. Moreover the dynamic emergence in the international division of labor of low-labor-cost, but as a working collectivity highly skilled, national formations (e.g. China, India) has objectively placed pressure on the hegemonic states, generating conditions of lower profitability. Finally, the channeling of a section of profits from production into the financial system[17] has retarded implementation of a broader restructuring of production and labour.

The crisis which appeared in the USA in 2007-2008 in the form of a housing price bubble represented a distillation of all preceding problems. Precisely because the financial over-extension was functioning as a pre-emptive ratification of the generation of future value and profits, it entailed a risk of sudden rectification and massive devaluation of holdings which, in conjunction with the latent tendency towards overaccumulation, resulted in global financial crisis.[18]

But the problem with this specific economic crisis is that it is really no more than the reactivation of the crisis of 1973, which was not solved but merely deferred, because all the elements of crisis persisted, in a latent condition. As indicated by Brenner, financial investment in the USA, the EU and Japan, on all indicators (product growth, investment, employment, salaries) has been steadily deterioriating since 1973 (Brenner 2002: Brenner 2008) – also see that data in tables 3 and 4 in the Appendix. For Brenner the problem is centred on the intensity of competition between American, Japanese and European businesses and given that the figures involved preclude withdrawals of fixed capital, a fall is induced in the average rate of profit in the productive sectors, leading to a slowing down of investment and a squeeze on wages. Increase in the rate of exploitation helped to avert a collapse in profitability but did not restore it to pre-1974 levels. An attempt was therefore made to solve the problem of capital accumulation through an increase in private consumption via an expansion of private lending. This merely ushered in a sequence of fiscal bubbles. The great failure in the bourgeois strategy was one of committing themselves so decisively to “expanding debt”, fuelling the conception that capitalists would be able to extract profits from the loans they issued to working people while at the same time strengthening demand for capitalist commodities (Wolff 2008). Recent developments have shown that such a procedure cannot not provide answers to the structural crisis of capitalism.

We have gone into some detail, then, on the subject of the global crisis, to show how profound the problems are and to what impasses the “solutions” so far proposed have led. What should become clear is that the crisis does not affect only Greece but that Greece is affected by it in its own distinctive way. We have traced, dialectically, the sequence “Greek crisis-crisis of the euro-global crisis” and the inverse of this. But here too Greece is playing the role of guinea pig. The desideratum is to find new ways of reversing the falling tendency in the rate of profit. The option that evidently predominates is that of changing the correlation between absolute and relative surplus value. This does not mean that relative surplus value will not continue to predominate, but there will be very great fall in labor’s share of the wealth produced, and a parallel increase in working time. For this reason in Greece too the measures are not confined to a new period of austerity but are symptomatic of an tendency to abolish the social gains of decades, on the pretext of finding a way out of the crisis.

8. Is there any chance of these specific measures leading to recovery?

On the basis of what we have established, we conclude that the measures taken will not only not contribute to reducing the deficit but are very likely to plunge the country into a deep recession. For a start the measures were not decided upon for the reasons that have been proclaimed, since as we have seen, the question as a whole is very different from how it has been presented, so that by extension if is difficult for there to be a correspondence between means and aims. That said, other questions also arise. The basic conception concerning fiscal reform centres on the notion that a cutback in overall demand will bring about a slump in sales resulting in a fall in prices and subsequent recovery of the market. What must not happen, argue the advocates of governmental policies, is that there should be a rise in wages, because that will reduce profits, investments and therefore employment. What does not register, not because of lack of intelligence but because these are clearly class policies, is that an increase in profits and investments becomes feasible only if economic policy focuses on expansion of overall demand. Otherwise the “cheap” goods will remain unsold, businesses will cut back on production, unemployment will increase and the recession will deepen. Why will that happen? Quite simply because the reduction in wages will lead to a corresponding reduction in private consumption, decreasing overall demand and bringing about a fall in fixed capital investments. Perceiving that their productive potential is not being sufficiently utilized, businesses have no reason to proceed with new investments – the more so when as in the case of Greece a large proportion of the fixed capital reserve has been accumulated recently. Τhe result is that there will be a reduction in input from all the factors comprising domestic demand, triggering an immediate rise in unemployment and so a further contraction in internal demand, etc. The bleakest aspect of the outlook is that it will be difficult for the Greek economy to return to its initial condition even when and if demand recovers. The reason for this is that by then a section of the capital reserve will have been liquidated, many companies will have gone bankrupt and part of the unemployed workforce will have lost its knowledge and its skills (Ioakeimoglou 2010a:).

To conclude, reductions in incomes will not solve the problem but on the contrary will raise a host of new problems (Thanassoulas 2010: 13). In the banking sector there will be a worsening of the precarious situation of the banks, with resulting new cutbacks in liquidity to the other sections of the economy (Lapatsioras-Milios 2010: 12)

9.Conclusion

As demonstrated by the “school of Althusser”, the peculiarity of the political is that it concentrates the class struggle at every level. In this sense the recent governmental measures are not simply a response to crisis, economic in character, but a clearly political strategy embodying specific class interests. The Greek ruling class finds itself at the centre of a maelstrom which is the product of a variety of different manifestations of class struggle: inability to continue with a specific mode of incorporation of the Greek social formation in the global division of labour,contradictions generated by the use of the euro in the context of global crisis, the requirement that all national formations should fall into line with the preferences of the powerful European bourgeoisies, the attempts at the international level to devise a new model for accumulation. Within this context our view is that the coming years will be characterized by attempts on the part of the national bourgeoisies to shift the cost of the crisis to the forces of living labor. The representatives of the popular interests, in politics and in the trade unions, will be called upon to forge effective strategies for turning back the offensive of capital. The future, apart from lasting a long time, promises to be extremely interesting…

Bibliography

Brenner Robert, 2002, The Boom and the Bubble. The US in the World Economy, London: Verso.

Brenner Robert, 2008, “Devastating Crisis Unfolds”, Against the Current 132, http://www.solidarity-us.org/node/1297

Brenner Robert, 2009, “What is Good for Goldman Sachs is Good for America. The Origins of the Present Crisis”,

http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/issr/cstch/papers/BrennerCrisisTodayOctober2009.pdf

Delastik Giorgos, 2010α, “So as not to be stupid”, Ethnos 11/2 (in Greek).

Delastik Giorgos, 2010b, “The big EU countries also deeply in debt”, Ethnos 6/3 (in Greek).

Economakis Giorgos, Spyros Sakellaropoulos and Athanasia Xenaki, 2006, “Direct Foreign Investments: Theoretical Investigation and Empirical Reconnaisance of Foreign Capital in Greece in the Period 1990-2002” in Vasilis Aggelis and Leonidas Maroudas (eds)., Economic Systems, Development Policies and Business Strategies in the era of Globalization, Studies in Honor of Professor Stergios Babanassis, Athens: Papazisis, pp. 677- 718 (in Greek).

European Economy, Autumn 2009.

Fleischbeck Heiner, 2010, “The Greek Tragedy and the European crisis: made in Germany”, Monthly Review 64: 56- 58 (in Greek).

Garganas Panos, 2010, “Crisis – from the banks to all the economy, ideology, politics” in Maria Styllou et al, Greek Capitalism and the Global Economy and Crisis, Αthens: Marxist Bookshop, pp. 38- 50 (in Greek).

Grauwe de Paul, 2009, “The Euro at ten: achievements and challenges”, Emprica 36: 5- 20.

Harman Chris 2008, “From the credit crunch to the spectre of global crisis” International Socialism 118, http://www.isj.org.uk.

Horafas Vangelis, 2010, “The Global economic crisis and the crisis in the European Union,” Monthly Review 64: 2- 21 (in Greek).

Incel Ahmet, 2010, “The acrobats of finance on stage again”, Αvghi 14/3, (in Greek).

Ioakeimoglou Ilias and Giannis Milios, 2010, “Indicators of Efficiency in the Greek Economy (1996- 2004)” in Vassilis Aggelis and Leonidas Maroudas (eds.), Economic Systems, Developmental Policies and Business Strategies in the era of Globalization, Studies in Honor of Professor Stergios Babanassis, Athens: Papazisis, pp. 577- 608 (in Greek).

Ioakeimoglou Ilias, 2010α, “The Coming Catastrophe”, http://www.ioakimoglou.net/assets/catastrophe.pdf. (in Greek)

Ioakeimoglou Ilias, 2010b, “Euro, the vulnerable currency”, Αvghi of 9/5/2010 (in Greek)

Ιoakeimoglou Ilias, 2010c, “Are wages to blame or the euro”. Αvghi of 22/4/2010 (in Greek).

Krugman Paul, 2010, “What caused the Euro-chaos”, Vima, 17/2 (in Greek).

Labor Institute of the Greek General Confederation of Labor, 2008, The Greek economy and employment. Annual Report 2008, Athens (in Greek).

Lapavitsas Costas et alii, 2010, Eurozone Crisis: Begar Thyself and Thy neighbor, RMF, http://www.researchonmoneyandfinance.org/media/reports/eurocrisis/fullreport.pdf

Lapatsioras Spyros and Giannis Milios, 2010, “Are they necessary, these measures the government takes to ‘save Greece”? Bloko 0: 12 (in Greek).

Kyprianidis Tassos and Giannis Milios, 2010, Editorial: “Camera Obscura. The inverted image of the “social market economy”, Theseis 111: 4- 13 (in Greek).

Melas Kostas 2010, “A first assessment of the Eurozone and the common currency”, Monthly Review 64: 22- 39 (in Greek).

Milios Giannis and Ilias Ioakeimoglou, 1990, The Internationalization of Greek Capitalism and the Balance of Payments, Athens: Exantas (in Greek) .

Milios Giannis, 2010, “The Greek economy in the 20th century” in Antonis Moisidis and Spyros Sakellaropoulos (eds.), Greece in the 19th and 20th century: Introduction to modern Greek society: Athens: Topos (in Greek) .

Mitrakos Theodoros and Georgios Symigiannis 2009, “Determinant Factors in Lending and Financial Pressures on Households in Greece”, Economic Bulletin of the Bank of Greece 32: 7-29. (in Greek).

Pelagidis Thodoris and Michalis Mitsopoulos, 2010, Turning point for the Greek economy. How progressive pragmatism can restore it to a trajectory of development, Αthens: Papazisis (in Greek).

Papantoniou Giannos 2010, “From development to Stagnation”, Vima of 3/1 (in Greek).

Stathakis Giorgos, 2010, “The Greek public debt, ‘bankruptcy’ and the Euro”, Avghi of 14/3 (in Greek).

Thanassoulas Takis, 2010, “Politics is concentrated economics”, Spartakos 101: 10- 13 (in Greek).

UNCTAD 2010, UNCTAD Handbook of Statistics, http://stats.unctad.org/Handbook/ TableViewer/tableView.aspx

Vergopoulos Costas, 2005, The Seizure of Wealth. Money-Power-Corruption in Greece. Athens: Livanis. (in Greek)

Vergopoulos Costas 2009, “Unfortunately we did not go bankrupt”, Εleftherotypia 17/12 (in Greek).

Vergopoulos Costas, 2010, ”Greece must bleed”, Εleftherotypia 26/2. (in Greek)

Wolff Richard, 2008, “Capitalist Crisis, Marx’s Shadow”, http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/2008/wolff260908.html.

APPENDIX

[1] For the case of Japan certain commentators assert that what is important is not the extent of the debt but the fact that to an overwhelming extent it is domestic debt, in contrast to Greece, where what is involved is external debt. This may help to explain the international pressures to which Greece is being subjected, but from a fiscal viewpoint there is no difference. At some point there has to be payment on the bonds and then Japan will be obliged to take out new loans, entering the same type of vicious circle as Greece.

[2] Let us cite characteristically the positions of G. Papantoniou, former Minister of National Economy in the Simitis governments: “Since the middle…..of this decade there has been an inordinate increase in the deficits of the external trade balance, reflecting delays in adaptation of the economy to the new competitive international environment. Private and public borrowing has been spiraling upwards The country has begun to live beyond its economic means in accordance with the high expectations generated by the success of the entry procedure. Savings have to a large extent been channeled into covering financial deficits. There has been a weakening in productive investments and a downgrading of competitiveness.” (Papantoniou 2010).

[3] According to another similar European Commission study the per unit labor costs for the Greek economy as a whole by comparison with the figure for the 35 other most developed countries of the planet increased by 15% in the period between 2000 and 2009. But the problem is that this fall in competitiveness is calculated in dollars, while each country has its own currency. The methodological error is thus made of factoring into labor costs changes attributable to fluctuations in exchange rates. If we want to ascertain the relative competitiveness of labor costs between Greece and other countries we must calculate the labor costs in the different countries in their national currencies. Following this methodology I. Ioakeimoglou came to the conclusion that during the period between 1995 and 2009 the labor cost per unit of product for the Greek economy as a whole compared, in national currencies, to the corresponding figure for 35 industrial countries, fell by 2% (Ioakeimoglou 2010c).

[4] Greek “hyper-consumerism” has recently been the target of much scathing comment. In reality this “tendency”: is nothing more than an attempt to maintain a living standard that had been established between 1960 and 1990 as a by-product of economic development and popular gains. Having said that, given that hardly any family (in contrast to the 1960-1990 situation) could survive respectably just on the salary of the father, women also entered the work force. And because the income was not sufficient even then to sustain an already acquired mode of consumer behavior the option was taken of resort to bank loans. For the whole problem to become comprehensible it suffices to mention that for the family to buy a house up to 1990 the salary of the father was enough. From the 90s onward it was necessary not only for the mother to work but for the couple to take out a loan.

[5] The comparative data quoted by Pelagidis-Mitsopoulos, which have to do with tax on dividends distributed to physical persons and income tax on physical persons also highlight the limitations on taxation of businesses in Greece compared to other countries of the EU15 (Pelagidis-Mitsopoulos 2010: 231).

[6] It is revealing that in 2006 the accumulated volume of Greek direct investments abroad came to only 8.0% of GDP, at a time when the average for the EU27 was 23.2% and with this level of performance Greece was ahead only of Slovakia, Rumania, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, the Czech Republic and Bulgaria, i.e. not even all of the former “socialist” countries.

[7] From this viewpoint we need only mention the purchase by the Greek state of American warplanes, French frigates, (defective) German submarines. It is clear that an overall reduction in public expenditure cannot be acceptable to the bourgeois power centres because drastic cuts in some kinds of public spending will come up against reaction from powerful imperialist countries. The cuts that “have” to be made cannot therefore be extended beyond certain acceptable domains: reductions in salaries, reductions in staff, reductions in pensions, reductions in expenditures that will not cause tensions with corporate monopolies and the imperialist centres.

[8] Some years ago Costas Vergopoulos showed considerable foresight in predicting what was then the future, sternly criticizing the state policies that were “preparing” the country for entry into the IMF: “Despite the external deficits and the inflation, it continued to be government policy to maintain the exchange parity of the drachma, that is to say essentially its permanent overvaluing for the sake of securing the favor of the European Monetary Union. But this would not only harm the international competitiveness of Greek prices but would raise the cost of foreign investment in Greece and foreign financing of Greece in real terms. Today, with the entry into the euro, this scenario is tending to unfold once again, largely cancelling the potential benefits to the country from monetary stability. For as long as the level of inflation in Greece deviates from the corresponding European level, in conditions of currency stability, the country will continue to face the same problems as those of the past: a fall in the international competitiveness of its products, along with a drying up of foreign investment and other funding from abroad, not to mention of course a steady contraction of net inputs from Europe, calculated in real terms (Vergopoulos 2005: 44-45).

[9] The marginal efficacy of fixed capital is defined as the change in GNP in the course of the year (t) in stable prices per unit of gross investment of fixed capital for the year (t-1).

[10] To be specific, in the period between 1997 and 2004 the annual rate of formation of fixed capital in Greece was just under 25% of GNP whereas in the EU it was kept under 20%. For investments in technological inventory there was an 11.15% increase, whereas in the rest of the EU the increase was just 3.14%. Reserves of fixed capital increased in Greece at an annual rate of 3.5%, compared to a figure of 2% for the EU as a whole (Vergopoulos 2005: 93- 94). Our assessment is that this significant development is not unrelated to the inflow of funds from the European support frameworks.

[11]In absolute figures the General Government debt increased from 204,018 million euros in 2006 to 216,381 million euros in 2007 (an increase of 12,363 million euros), 237,196 million euros in 2008 (an increase of 20,815 million euros) and 272,300 million euros in 2009 (a change of 35,104 euros). This large increase is a result of the necessity to repay short-term loans (of a duration of up to three months), the government having contracted many of these during the period in question). More specifically, short-term debt increased by 8,091 million euros in 2006 to 24,723 million euros in 2007, 25,674 euros in 2008 and 36,904 million euros in 2009.

[12]There are certain aspects of the current situation that should not be overlooked because they show how far the implications of an extension of the crisis in the Greek economy could in fact reach. A significant part, for example, of the banking system of Bulgaria (it is estimated at around 30%) belongs to Greek banks. A collapse of the Greek economy would therefore introduce elements of crisis into the Balkans generally.

[13] Of course some contribution was made to this by the concealment of real data by the preceding government with resulting indeterminacy in the money markets as to the real state of the Greek economy.

[14] In a very interesting article Ahmet Incel analyses the role played by specific American financial institutions, above all Goldman Sachs, in generating the pressures to raise the cost of risk insurance in the Eurozone through over-inflation of the financial problems of Greece, Spain and Ireland. Its chosen weapon for this purpose was the so-called Credit Default Swap (CDS), these being insurance contracts against the danger of a company or a state defaulting on its debts. The greater the risk, the higher the interest rate (Incel 2010). Up to the time of activation of the support mechanism, the risk quotient for Greece in the CDS markets had skyrocketed from 120 to 700, meaning that the financial markets estimated that there was a 60% chance of Greece not being able to meet its loan repayment obligations in the next five years. To appreciate how inflated the risk in question was made to appear, suffice it to mention that the corresponding indicator for Rumania, which is in an even worse fiscal situation, was 265. By way of comparison it is estimated that the risk of Morocco not being able to pay off its debt was eight times smaller than the risk with Greece, and that of Lebanon four times smaller!

[15] We should make it clear at this point that intra-European disagreements had to do with further support for Greece and not the necessity as such for the recent governmental measures. On the contrary, all the members of the Eurozone were openly in favour of the measures. .The reason for this is that a climate a inculpation of Greece had been generated for its persistence in deviating from what the imperialist centres and the international markets wanted (resounding defeat of the workers’ movement, even greater redistribution of income in favour of capital, increase in retirement age, greater flexibility in labour relations, displacement of the trajectory of politics onto an even more conservative, neo-liberal path.)

[16] Our assessment is that a significant role in the wage freeze was played by the reunification of Germany (Lapavitsas 2010), for two mutually supportive reasons: On the one hand in the East there was no tradition of trade union practices and on the other the lower standard of living in the East facilitated a squeeze on labor costs in the West.

[17] According to a report by JP Morgan Securities, between 2000 and 2004 the turn towards the fiscal system on the part of businesses in the G6 countries involved sums in excess of 100 billion dollars (Harman 2008).

[18] Obviously in the space available in this article it is not possible to make extensive references to the subject of the crisis. The low profit margins and correlations of power that precluded any real increase in salaries contributed to over-inflation of the fiscal sphere. Businesses purchased financial products to increase their profitability; households contracted consumer loans and housing loans because they were not able to purchase houses and other commodities out of their salaries. The result was a huge increase in borrowing and the conversion of loans into special types of securities that were purchased by a succession of depositors (businesses, insurance funds, other banks). Initially this innovation was regarded as particularly promising because in the event that some enterprises encountered difficulties this would not be confined to just one lending institution, because the risk had been shared between different purchasers. But when house prices began to collapse it became evident that the system suffered from a twofold problem: on the one hand it wasn’t clear who had possession of the problematic loans, with the result that the banks were unable to assess the reliability of each individual client and finally stopped lending to everyone. On the other hand this generalized absence of clarity emptied the reserve ratio of any meaning, and likewise the capital ratio, so that banks were unable to monitor the rate of credit expansion (Garganas 2010: 40-41)